Did a part of healthcare actually...get disrupted?

On health systems and telehealth implementation

As long as I’ve been a healthcare groupie, the promise of technology “disrupting” healthcare has remained out of reach. A lot of healthcare still sucks.

But a recent report made me start to wonder if we’re actually witnessing disruption in real time. According to a report released by the Chartis Group (and shared by Health Tech Nerds last week), health systems are starting to see telehealth as a major competitor—82% of health systems surveyed reported that telehealth companies like Teladoc and Amwell are competitors. This is second only to the percentage of surveyed health systems that named other health systems as competitors.

Much has been written about the rise of telehealth during the pandemic, and just as much has been written predicting whether it would retain its popularity even as COVID cases wane. Less discussed is whether telehealth is taking just enough margin off the top to change the role of health systems altogether.

Always studying, never implementing

But for their reputation for bureaucratic slowness, hospitals seem like the natural birthplace of major telehealth implementation. They have the biggest budgets, they often have innovation teams or leaders, and it is well-documented that receiving care at a hospital can cause secondary infections—so there’s a medical incentive to telehealth, as well as a consumer one. But the actual implementation hasn’t really occurred.

It’s more forgivable that health systems didn’t have a coherent program before the pandemic (one of my favorite anecdotes from 2020 is when the Mayo Clinic was so unprepared for their workers to go remote that the CIO “made a decision in an afternoon that we were going to take existing desktop computers and ask people to drive into the office and take them home”). Now, after two years of demonstrated value and consumer interest in telehealth, the Chartis Group found that 93% of health systems have plans for investment in digital capabilities and programs…but most are still in the planning stages.

On a recent episode of the podcast Relentless Health Value, guest Liliana Petrova, an expert on customer/patient experience, explained to host Stacey Richter that this delay is hinged on a few structural problems that health systems tend to have, which include, among others:

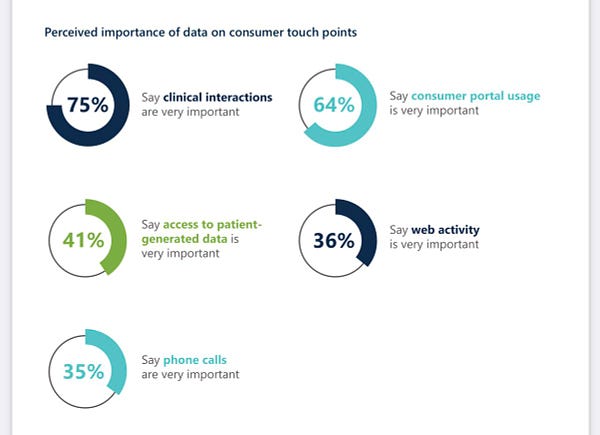

They don’t collect patient data systematically

Their IT teams still act like support desks, rather than members of the care team

In other words, hospitals don’t collect the data that would guide them to making patient-oriented decisions around telehealth, AND they don’t have the staff to make it happen.

Are health systems even looking at telehealth in the right way?

I think there’s another reason that health systems are struggling to implement coherent telehealth programs, and that’s that they don’t know what they’re optimizing for. Not only do health systems not have comprehensive patient data to build a more consumer-friendly telehealth program, but they might not even care about it being consumer-friendly in the first place.

Health systems can optimize for a few things, none of which are entirely mutually exclusive, but all of which require a different strategy: Patient satisfaction, revenue, visit capacity, provider satisfaction, and customer acquisition (and I’m sure there are others).

Instead of choosing one of these goals, health systems seem to be firing wildly at telehealth options, offering a software that’s challenging for everyone to use, not making it clear when a patient should opt for telehealth instead of in-person or even publicizing that there is a telehealth option, charging facility fees for remote visits, and setting up a system that requires doctors to perform a confusing mix of telehealth and in-person (rather than, say, building a workflow that alternates telehealth and in-person days).

The Chartis Group report seems to support my hypothesis here. When asked their primary reason for investing in digital transformation (a category which, to be fair, includes telehealth as well as other digital programs), a majority of 61% said their primary reason is, of all things, improving outcomes—never mind that it’s totally unclear how they would accomplish that.

(The next most popular answer to this question, with 23% of respondents, is “reducing the cost of care,” which seems more likely…but reducing the cost of care for whom? The hospitals?)

A related problem is happening with patient portals, with a majority of health systems declaring them very important…and then failing to implement them in any kind of logical way.

Is this…disruption?

I’ve never gone to business school, but there are a few major cases that everyone seems to know, one of which is the Kodak case. As the story goes, Kodak, a large camera and film manufacturer, invented digital cameras. But the company stumbled in its strategy for capitalizing on the technology, and a few years later was forced to file for bankruptcy. At least the way I’ve heard the case told, this is a classic example of disruption of an incumbent.

Granted, I highly doubt the U.S. will ever swing far enough toward telehealth that health systems would have to file for bankruptcy, but I suspect we’re seeing a real-time slippage in the supremacy of hospitals in American healthcare. In a new era of telehealth for primary care, urgent care, and some chronic condition maintenance care, hospitals might lose their ability to attract and retain patients outside of procedures.

(Then again…would that actually be financially bad for hospitals? It might not be, given that procedures are often the highest margin service that hospitals provide. This shift might mean that hospitals have to devolve from their current infrastructure-heavy models into more of a network of ASCs. But also this is a projection so far in the future that I may very well be wrong.)

As I’ve argued before, telehealth is a commodity, and it’s increasingly a problem that hospitals don’t offer this commodity with the same ease as other companies. Health systems have held the top provider position for so long that my guess is that they’re used to being the gatekeepers for patient portals, EHRs, even surgical technology (the DaVinci robot, for example).

In other words, it isn’t that Amwell is the future, it’s that health systems are failing to adapt to a world with a new commodity product—consumer-friendly telehealth—allowing other models to rise in the place of health systems. And that might be disruption.

This information shouldn’t be taken as investment advice (obviously), and the opinions expressed are entirely my own, not representative of my employer or anyone else.