Everything in healthcare is a bank now

More inefficiency = greater returns for some

Administrative and other waste in healthcare is one of those topics that everyone knows about and begrudgingly accepts. But one thing I’m increasingly convinced is contributing to that waste is that more healthcare entities are operating like banks, rather than entities primarily administering healthcare services.

Lending money

UnitedHealth Group is, as usual, on the forefront of this enterprise. As my colleague Emma Freer wrote in a recent whitepaper, UnitedHealth Group is a Bank, the 2003 Medicare Modernization Act, which established health savings accounts (HSAs), was an exciting moment for UHG. Months before the MMA was passed, UHG founded Exante Bank and purchased Golden Financial Bank, an HSA pioneer.

Exante Bank was chartered as an industrial bank, which is a specific designation meaning that the industrial bank is owned and operated by a nonbank parent company. Industrial banks are also not supervised by the Federal Reserve. This means that UHG can essentially use its financial institutions outside many of the regulations and oversight that exist for commercial banks.

UHG’s financial components eventually became Optum.

In 2021, Optum announced an intended acquisition of Change Healthcare, the payment rails for a huge percentage of the physician reimbursement and claims transactions happening in the U.S. every day. Although the Department of Justice sued to block this merger, a federal judge ruled in favor of UHG, and the acquisition went through in 2022.

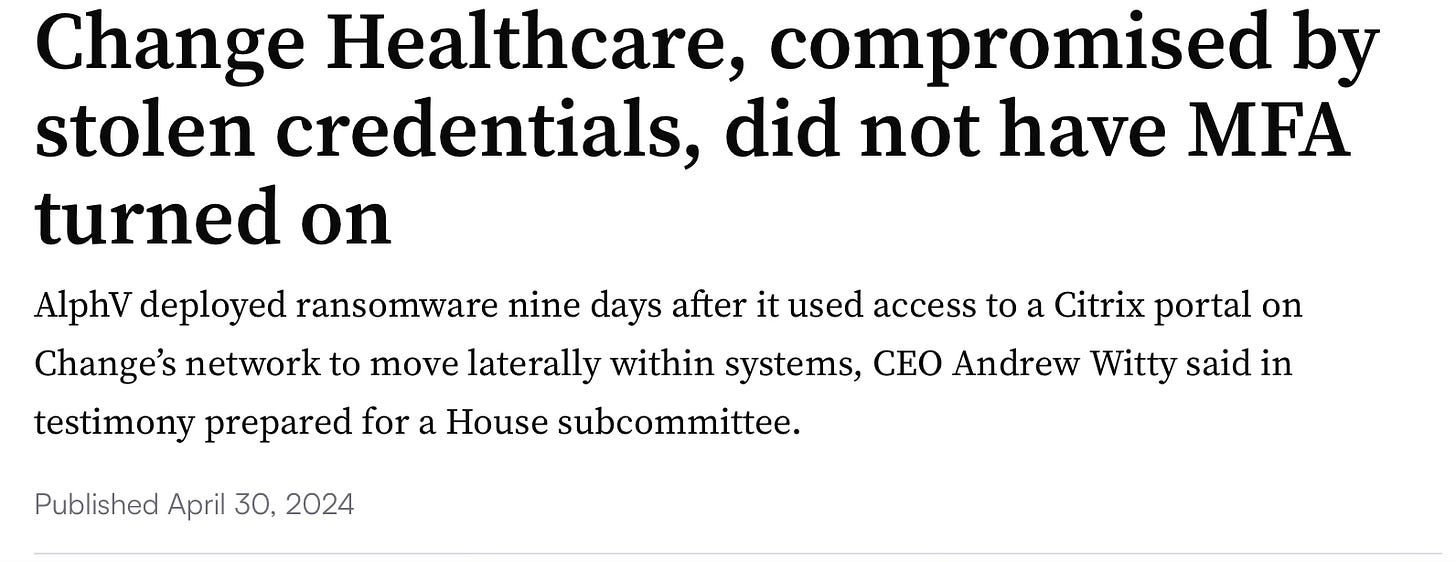

Less than 18 months later, many of the concerns raised by the DOJ and others by UHG/Change’s combined size were revealed to be accurate when Change experienced a cyberattack on its systems (it didn’t have multi-factor authentication protecting its data on roughly 55 million Americans…). Change’s payment system went offline in the wake of the attack, leaving physicians unable to access reimbursement for many of their claims. Eventually, this became a backlog of at least $14 billion owed to physician practices.

For physicians operating on thin margins — margins made even thinner because of claims denials (particularly by UHG) — this pushed many over the edge. Practices closed or were acquired by UnitedHealth. Optum Financial launched an emergency loan program for providers, and then-CEO Andrew Witty testified before the Senate Finance committee that Optum would not seek repayment until physicians self-reported that their business had returned to normal.

However, just a few months after Witty’s testimony, physicians began receiving notices from Optum that full repayment would be required within just a few business days — or Optum would begin garnishing reimbursements. As I wrote earlier this year, this saga showed UHG behaving almost cartoonishly evilly, becoming a byword for the problems with American healthcare.

Denying claims to hold onto money

But acting as a loan shark (as Emma puts it in her paper) to physicians isn’t the only way that healthcare entities have been acting as banks. As the biggest entities have grown in size and revenue, and the interest rate environment holds steady at a relatively high rate compared to recent years, these corporations have also sought to hold onto their money for as long as possible — even if it means delaying payment to other entities to which they owe money — to reap the rewards of investment.

Payors denying reimbursement claims from providers enables payors to retain more cash on hand, keeping their total amount invested high and their shareholders happy. Meanwhile, providers and health systems struggle to get reimbursement, requiring their administrative teams to continually refile and appeal denied claims and going after individuals (with much less money than the payors) who haven’t covered their whole copay.

Other, non-insurer entities do this too. Wholesalers, which control the flow of pharmaceuticals and pharmaceutical dollars between manufacturers and pharmacists, tend to have contracts that give them 3 months to reimburse pharmaceutical manufacturers — but require pharmacists to reimburse within 30 days.

Why does this matter?

These dynamics most dramatically affect independent physicians and pharmacists. Without the ability to cudgel big payors and wholesalers into paying, they’re left begging for scraps (and taking emergency loans from Optum Bank). Eventually, these independent providers are essentially coerced into joining bigger health systems or practices that provide worse care at a higher cost.

As my colleague Matt Stoller has written, optimizing everything for shareholders has become a dominant policy goal in America, even when it affects quality of care (or health system reimbursements, or physicians’ ability to stay independent). The stagnation and administrative waste inherent in allowing corporations like payors and wholesalers to hold onto cash just to please their stockholders while everyone else suffers is a disaster for American healthcare as a whole, but it just keeps happening.

And, ironically, focusing purely on financialization and shareholder value is worse for everyone in the end! Innovation goes down; the most financialized companies become hollow, bloated, and obsolete; and everything begins to suck more. As the Wall Street Journal pointed out last year, health insurers are becoming chronically uninvestable. You can try to please shareholders, but it turns out you really can’t.

Wouldn’t it be better to actually provide patient care at a reasonable cost?

Fascinating and well articulated. I wrote to my husband who is a business owner and has a finance background…

You should read this.

I can unpack. Really powerful POV on the challenge — United health owns a lot of practices via Optum Health, their division.

Also the notion of the denial of payments being a form of holding on to cash so they can trade. While premiums and coinsurances get collected timely. “

higher health care prices benefit payers and benefit pbms. value based, accountable care, managed care- these are all Orwellian Newspeak- and many smart people are following this believing in this noble cause, which is anything but. there are solutions- the industrial complex does not want them to occur; the status quo remains too profitable. Reform at the highest levels is needed. AI is helping innovators opt out of the current heist; but this will take time.