How hospitals are shifting supply chain strategies

And Optum's moves into group purchasing

Like many Americans, I hadn’t really thought about supply chains until two years ago. Since then, I’ve thought about them a lot. Consumer supply chains remain fragmented and slow, making it more difficult to order furniture, cars, toys, and other goods that we’ve gotten used to having readily available.

At the same time, the supply chains that serve hospitals—delivering things like surgical gloves, generic medications, syringes, and IV tubing—are also falling apart.

Hospital supply chains are still a mess

In an article last November, Becker’s Hospital Review declared that “Supply chain issues are here to stay.” A Kaufman Hall report found that 99% of surveyed health systems are having supply chain issues. Premier, a large GPO (more on GPOs later) released a long list of all the current strains on the supply chain.

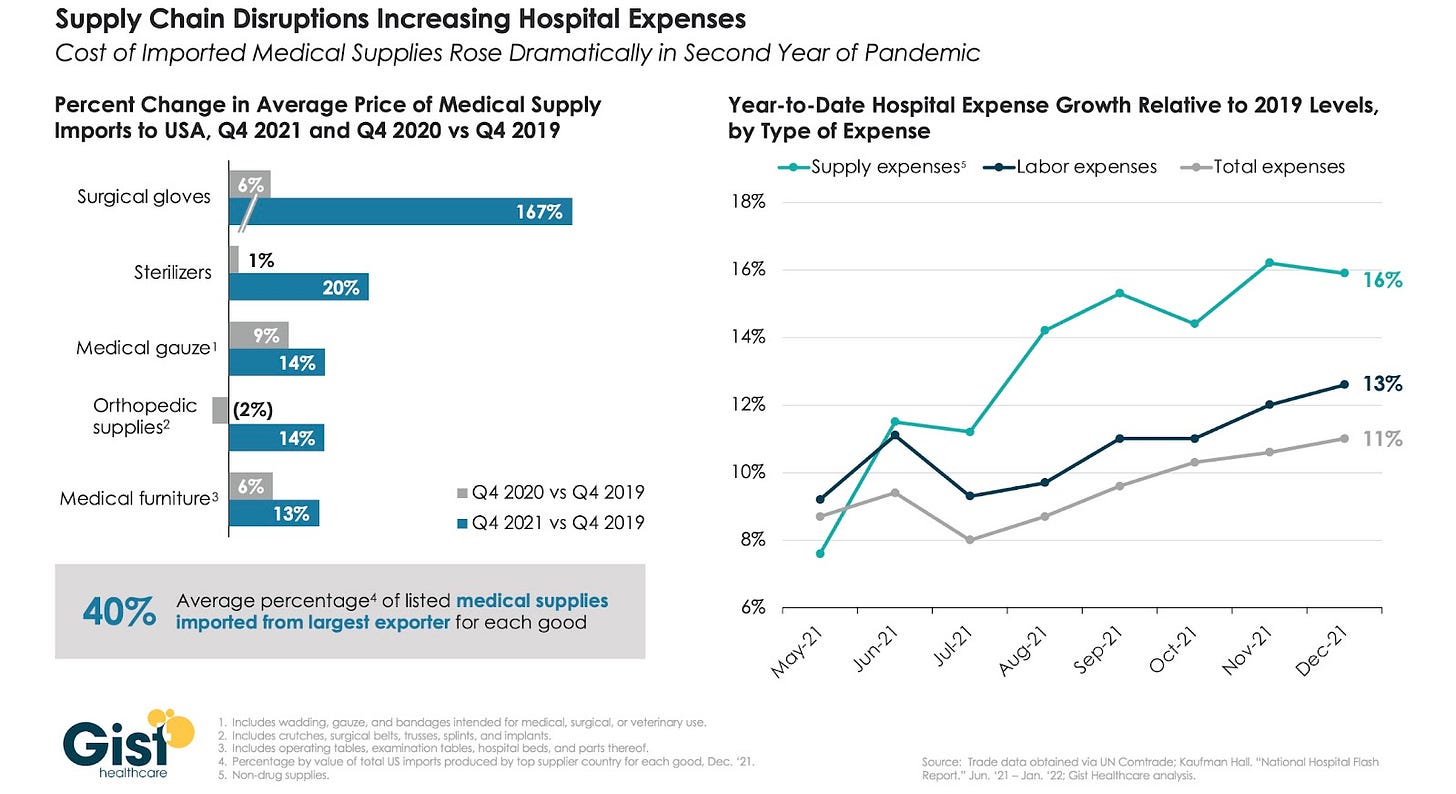

Prices on basic supplies are up as well:

(Ironically, some hospitals now have a glut of PPE, originally one of the worst shortages early in the pandemic.)

What strategies are hospitals using?

All these supplies are obviously essential, so health systems are using a variety of strategies to shore up their inventories.

Before COVID, health systems typically worked with a group purchasing organization, or GPO. GPOs are middlemen that handle much of the bulk purchasing of commodities for health systems and other providers. It’s an important service, but there are just a few major GPOs in the U.S., and that dynamic both makes it harder for a health system to get a favorable contract and makes the resulting supply chains weaker, with less redundancy.

Health systems also tended to order supplies “just-in-time,” a supply chain strategy popularized in the 1970s by Japanese companies. Just-in-time prioritized lean inventories and well-oiled supply chains that delivered necessary pieces just in time for them to be needed. This strategy freed up revenue that had traditionally been stored in inventory, but it also made the whole supply chain more brittle and prone to reverberating shocks. (For non-healthcare examples of how complicated this can be, see this 2019 article about tiny screws used in iPhone assembly.)

All of this to say that, when COVID hit, many health systems were left dependent on their GPOs and without much leftover inventory to weather the disruption.

Two years in, health systems have adapted, many by partially taking on the role of GPOs themselves. In interviews with health system leaders, Gist found that the leaders “stress that they don’t expect their group purchasing organizations to save the day, and are instead proactively reevaluating suppliers and distribution partners for their most critical supplies.” (At the same time, many health systems have kept their contractual relationships with GPOs; the contracts are too difficult to change.)

Larger health systems seem to be weathering the supply chain storm better—which isn’t terribly surprising, given that they have more people and more resources to devote to the problem. Danielle DeBari, SVP of Business Operations and Chief Pharmacy Officer of NYCHHC told Becker’s:

[Our] strategies include forecasting products and materials and adjusting timelines on our end for delayed shipping, diversifying our suppliers, and building relationships with these suppliers. By planning far enough in the future and addressing anticipated issues early, a health system can get ahead of a challenge and pivot so its patients and overall communities do not experience any disruption in care.

Wellstar, another health system, uses a consolidated service center (CSC) model, a model that centralizes ordering and inventory for the whole system. This allows for more flexibility and bulk purchasing direct from suppliers, as the SVP of Supply Chain explained to Becker’s:

We've done our best to work directly with product manufacturers as opposed to distributors, so we've done our best to try and eliminate the middleman. And by doing so it gives us much stronger relationships with our manufacturers, and it affords us the opportunity to establish our own distribution center. So we have between 20 and 40 days of stock on hand for all of those critical items.

Smaller health systems, which may lack the revenue or space to hold extra inventory, and which likely lack the bargaining power to get much attention from GPOs or suppliers themselves, seem to be getting hit by these shifts harder. The large health systems interviewed by Becker’s explicitly noted that supplies were no longer one of their top priorities. Smaller health systems were (in my count) more likely to express that supply chains remain an ongoing concern.

Regardless of size, many health systems have begun paying closer attention to their supply needs and potential shortages—made more necessary by the fact that it can now take 14 days to get a shipment of items that once took 2 days to receive.

The sun never sets on the Optum empire

Apart from health systems starting to shift their strategies, GPOs might (?) be about to get some quiet competition from another angle. Over the last year or two, PBMs associated with Express Scripts, CVS, and Optum have launched their own GPOs.

Given that the PBMs are the entities launching GPOs and not the parent companies, these new GPOs seem to be involved primarily or solely in generic drug distribution specifically. Adam Fein of Drug Channels notes:

My $0.02: These organizations provide a novel way for PBMs (1) to extract incremental fees—on top of the usual administrative fees—from drug makers while (2) creating a non-rebate flow of funds for themselves.

He’s probably right. However, I feel free to speculate that Optum, with the largest network of physicians in the country, might eventually try sourcing some of its own commodity products beyond generic drugs, especially if supply chains continue to be as messy as they are right now.

Conclusion

The shift in supply chain strategy caused by the pandemic seems to be more or less permanent.

Long term, I wonder if health systems will eventually feel the pressure enough to stand up their own GPO. They’ve shown themselves to be able to band together to source items like generic drugs and sell patient data.

That said, if the largest health systems have figured out their own strategies, there is less impetus for some kind of group project on sourcing commodities. It might be, once again, Optum…leading the way.

This information shouldn’t be taken as investment advice (obviously), and the opinions expressed are entirely my own, not representative of my employer or anyone else.