Patients and providers actually enjoy tele-mental health

What does this mean for the future?

I’ve been thinking about the trauma of the last year and the practice of therapy a lot lately. The experience of COVID-19 taught us a lot of new vocabulary—superspreader, herd immunity, reactogenicity (I got my second dose today 😭)—but the impact went deeper. 2020 was also a huge, life-altering experience. I was at an outdoor, vaccinated gathering last weekend with people mostly from New York, and they all have specific memories of constant, eerie ambulance sirens for those first few isolated months. What has this done to us? We probably won’t fully know for a few years at least.

I’m also halfway through two interesting books that are related to the history of therapy, and it’s been fascinating to see how the practice of therapy has evolved over decades. The first book is Genius and Anxiety: How Jews Changed the World, 1847-1947, which is a fun, kind of dishy history of Jewish artists, thinkers, and quite a few therapists. The second is the slightly more relevant The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma.

In the midst of all these thoughts about therapy and how it’s practiced, Dr. Carlene MacMillan reached out with data and asked if I’d be interested in writing it up. (She isn’t paying me and didn’t ask for me to have any specific takes on the data, she just sent it to me out of interest.)

Patient preference

In a win for therapy access, the surveys done by Dr. MacMillan’s group show that most patients were very positive about using tele-mental health, even though the patients at the clinic surveyed are generally higher acuity than average. Surveyed patients expressed appreciation for the lack of commute time, and the ability to seek care more frequently without worrying about blocking large chunks of time, which appeared especially helpful for parents.

Common complaints should be familiar to all Zoom users. Patients noted that it could be harder to gauge their therapists’ reactions, or similarly, that they worried the therapist wasn’t seeing the patient’s whole range of emotions. A few patients noted the presence of Zoom fatigue, and more patients than I would’ve guessed said that it was easier to forget appointments if they were online.

Provider preference

The patient data was more positive toward Zoom than I would’ve expected. But the provider data really surprised me.

Providers apparently love telehealth!

Eighty-one percent of the providers surveyed by Dr. MacMillan (all within her practice, and with n=17 except where a provider skipped a question) reported feeling more positively toward telehealth than they did a year ago. The remaining 19% reported feeling neutral.

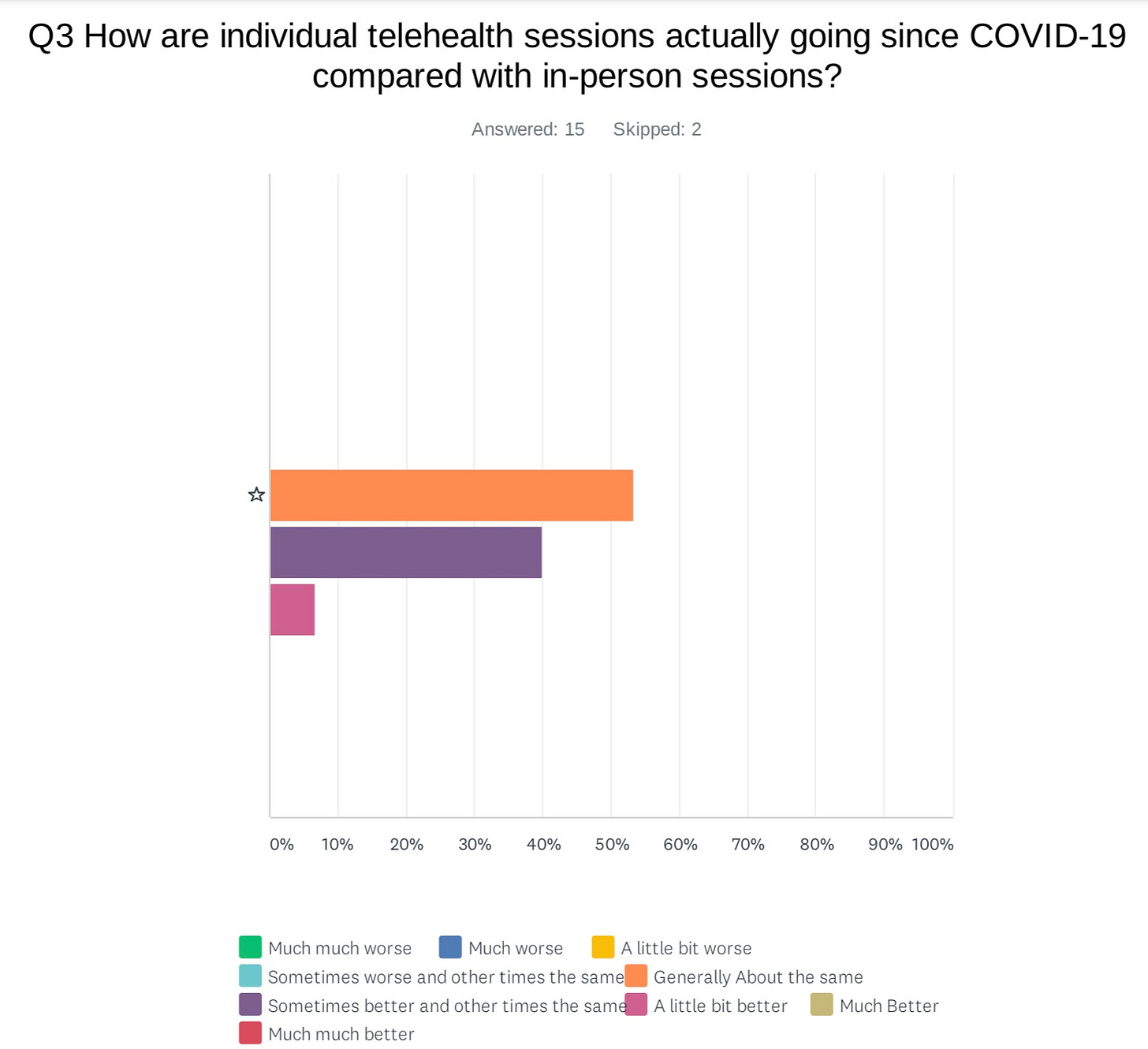

Providers also reported that their tele-mental health sessions were going the same or better than in-person sessions had.

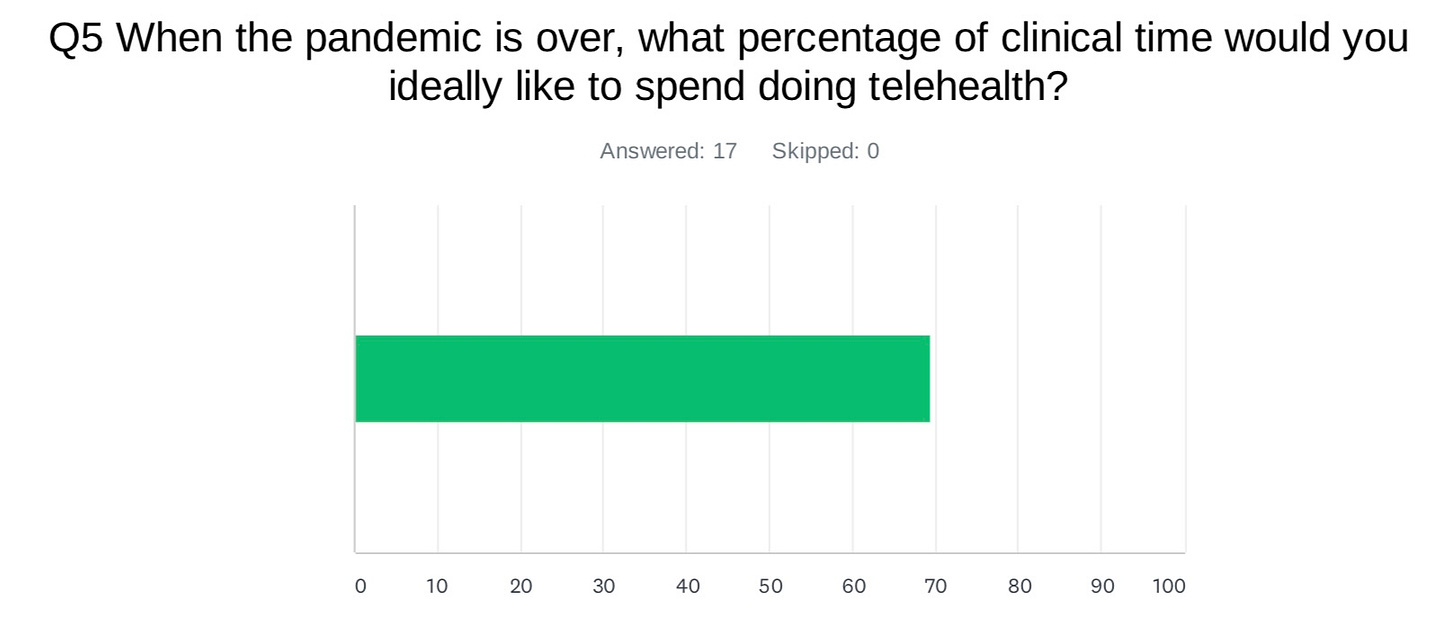

And finally, the surveyed providers reported wanting an average of nearly 70% (!!!) of their time post-pandemic to be spent doing tele-mental health.

There are a few obvious ways to interpret this data. There’s a chance that Dr. MacMillan, being the kind of innovative provider who thinks about tele-mental health and runs surveys with her providers, has gone above and beyond to make telehealth comfortable and easy. The data may not be representative, or they may only apply to mental health providers in the Brooklyn area.

All of that notwithstanding, I think there’s something here, on both the patient and provider side.

What does this mean post-COVID?

Three weeks ago, I wrote:

Traditional therapy, performed in-person, will certainly come back—but I think it will segment into being primarily for (1) those with severe mental illness and (2) those with money.

Severe mental illness will probably always be best served with in-person treatment. It’s hard to imagine long-term psychiatric medication and condition management being best-delivered through telehealth—although I’m very willing to be wrong on this.

But for those without severe mental illness, in-person therapy might become a luxury good. As middle-income people seek therapy through apps like Ginger and Real, in-person therapy might become a wellness activity similar to regular facials. Therapists could build out the comfort of their offices and charge more to provide a relaxing and tranquil space for others to unburden themselves away from the possibility of their family overhearing them, or the frustrations of a spotty wifi connection.

Dr. MacMillan’s data is sharpening my opinion on this. I see in-person therapy evolving in a few related ways:

First: in-person therapy becomes a luxury good for lower acuity patients.

Second: in-person therapy remains an essential service for those with severe mental illness.

Third: a hybrid tele- and in-person model becomes standard for those with moderate to severe mental illness, those who need frequent medication adjustments, or those who require adjunct therapies like esketamine.

Fourth: tele-mental health becomes a mass-produced product, widely available for white collar workers (particularly those with employers who compete on benefits). The quality dips, but the increase in access balances out the lower quality.

Tele-mental health as a scalable commodity

The therapy industry’s scalability is directly bounded by the lack of qualified mental health professionals available. In other words, the essential reliance of therapy on direct patient-provider hours makes it both expensive and more directly constrained by workforce availability. Unlike some specialists, therapists can’t schedule overlapping 15 minute patient visits and then just force everyone to wait.

To scale tele-mental health, then, companies have to either hire a lot of therapists, or uncouple the experience of therapy from direct face time to something broader or more asynchronous: group therapy, pre-recorded classes, or a texting model, for example.

At the same time, these concessions for scale make tele-mental health more of a commodity. (I wrote more about this regarding general telehealth a few weeks ago.)

A commodity means that the good or service is more or less interchangeable to the end user, so the user primarily chooses based on price. Wheat, water, and milk are all commodities (there are obviously some differences between different brands, and often utility companies have local monopolies such that users can’t choose based on price, but work with me here).

As tele-mental health companies scale, therapy becoming a prepackaged good that can simply be delivered at scale, rather than a thing that is uniquely tailored to each individual patient, seems inevitable on some level. But again, as I said above, I think the increased access probably makes up for any dip in quality.

Commodity and the art of being a therapist

What does this mean for the providers, though? In The Body Keeps the Score, the author talks about how his best psychiatry teacher was his patients. By working closely with each one, and with some trial and error, he developed his practice. This seems less likely to happen if providers are delivering “prepackaged” care to a larger slate of patients.

One of my friends recently pointed out that Karl Marx focused on a different part of the definition of “commodity;” he (on brand for Marx) directed his attention to the worker producing that commodity. In Marx’s view (I realize I am dramatically simplifying and possibly mixing several strains of philosophy here, but I promise I have a point), the more commoditized the good, the more alienated the worker is from their product. In other words, the commoditized product becomes mass-produced and less of an artisan good, and the producer feels like less of an artisan. I think it’s entirely possible that therapists, perhaps the group of medical providers who rely on their instincts and experience the most, experience something like this as tele-mental health becomes more of a commodity.

Of course, there is a long history of physicians (and opportunistic groups) opposing progress in the medical space on the grounds that it would take away their essential physicianness, their ability to view the patient holistically through the prism of their knowledge and experience, and make judgment calls. And, again, I think the potential increased access with scaled tele-mental health companies is important. But also subsuming providers entirely to an assembly line has the potential to cause problems.

In early 2020, I wrote a piece for Current Affairs talking about the increased alienation (manifesting as burnout) that many health care workers were feeling—and this was just months before COVID-19 made everything much, much worse. In the piece, I argued that the increased corporatization of medicine—devolving decision-making to far away executives, rather than maintaining some kind of health care worker engagement—was related to the increased chatter I was hearing among hospital-employed physicians calling for some kind of labor organizing or strike.

Needless to say, it’s a complicated balance. To deliver health care—and particularly something like therapy, which requires so many hours per patient—requires some kind of scaling, which in turn requires some kind of assembly line that necessarily removes a level of the artisanship of the provider.

Conclusion

This is what I’m thinking about when we look to the future of tele-mental health. I don’t have all the answers. If you have more answers than me, let me know! I’m obsessed with thinking about what will happen to health care post-COVID.

If you’re interested in tele-mental health, I’ll leave you with one more recommendation: this Slate What Next podcast episode, which argues that the newest kinds of scaled tele-mental health—particularly therapy by text—may not be the same as talk therapy at all. But, the hosts conclude, that doesn’t mean it has no therapeutic value.

This information shouldn’t be taken as investment advice (obviously), and the opinions expressed are entirely my own musings, not representative of my employer or anyone else.

It’s a bit tough to accept all of the conclusions here since the number if people in the survey appears to be 17. It would be more interesting to see this data with a larger sample size.