Pharma tariffs and what's next

I spent a week reading Federal Register comments

On April 2, the Trump administration announced sweeping tariffs on nearly every country on earth, calling it Liberation Day. Notably exempt from these tariffs, though, were pharmaceutical products. Trump signaled his intentions to add tariffs to pharmaceuticals but held off.

That same month, the Department of Commerce opened an investigation into the national security implications of existing pharmaceutical supply chains under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. This statute allows the administration to adjust imports if the current landscape is deemed a national security threat — broad language, and the administration has used it broadly.

The order specified that the agency was investigating all aspects of pharma products, including active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), which are the precursor compounds for drugs, as well as pharmaceuticals in general.

As part of its investigation, the Department of Commerce requested comment from interested parties. Anyone could leave a comment. Perhaps here I should note that I love to read comments on stuff like this. It’s the more lawyerly version of reading Facebook comments; people are dramatic and it surfaces unexpected areas of interest.

(One comment on this order, for example, was mostly just a person complaining about their health: “I went up for [sic] pants sizes, severe fatigue, I was cold, etc.. Not long after these symptoms started, I began having waves of heat across my body, no, not menopause.” I sincerely hope this person feels better soon, but it’s basically the same as reading Facebook. Anyway.)

A few areas of agreement emerged from the comments submitted by pharma companies.

Generic vs. brand name

Generic and brand name manufacturers had slightly different reactions to the request for comment.

First, in case you aren’t as deep in the sauce on pharma manufacturing as I am, a few details. There are a few different types of pharmaceuticals, but the majority are oral drugs in pill or tablet form. These are usually produced through chemical manufacturing of the active pharmaceutical ingredients (API), which are then chemically combined with inert, edible binders and pressed into shape. The supply chains for these drugs are complicated and global. The FDA doesn’t require manufacturers to share the source of their API, and manufacturers may source API from several different plants. They may or may not own these plants themselves.

In general, supply chain location and process is determined in part by whether the end drug is a brand name or a generic. Brand name drugs, or those that are currently patented and for which there aren’t direct substitutes, tend to be more expensive. Manufacturers of brand name drugs have the capital and the incentive to invest in a strong supply chain. These drugs tend to be manufactured in the U.S. or ally countries, with Ireland as a notable hub.

Generic drugs, or those which are off-patent, are a different story. Generic drugs compete on price. Over time, a few manufacturers have emerged that specialize in producing generic drugs. These manufacturers — Teva, Viatris (formed from a 2020 merger between Mylan and Pfizer’s generic drug division Upjohn), Sun Pharma, Sandoz, and others — operate on thin margins and have less of an incentive to own the end-to-end supply chain. Quality is a well-documented issue with generic drugs, and the vast majority of APIs for generics come from China and India (and as I’ve written before, some data suggests that the majority of India’s API itself comes from China).

Domestic facilities and semaglutide packaged as kitten food

The manufacturers of brand name drugs emphasized their U.S.- and ally country-based supply chains and their commitment to building new facilities in the U.S. The comment from PhRMA, the major biopharma lobbying group, noted that nearly two-thirds of all finished pharmaceuticals consumed in the U.S. are made in the U.S.

A few key points here — PhRMA is quantifying that two-thirds percentage by value, not by volume, because brand name drugs are far more expensive than generics. This number likely also includes super innovative but super expensive gene-editing treatments. And the comment specifies that the number is of finished pharmaceuticals, an important distinction because pharmaceuticals can be finished in Europe and the U.S. but still have API coming from China (PhRMA’s letter also notes that slightly more than 50% of API by value comes from the U.S., but again, that’s by value).

PhRMA and member companies like Pfizer and Sanofi emphasized the difference between innovative (brand name) drugs and commodity (generic) drugs. They noted the supply chain differences of both and requested that tariffs take that into account. Amgen requested that any tariffs be tailored to countries of concern, rather than broad global tariffs on pharmaceutical imports.

Meanwhile, Novo Nordisk, the manufacturer of Ozempic, really wants tariffs on generic semaglutide, which is being imported by compounding pharmacies to sell as a cheaper, generic version of Ozempic, including through telehealth portals like Hims.

As an interesting aside about the quality of these compounded semaglutide products (at least according to Novo Nordisk’s comment), of the 19 Chinese manufacturers that shipped generic semaglutide into the U.S. between 2024 and early 2025, 5 weren’t registered with the FDA and 6 hadn’t been inspected by the FDA. Novo Nordisk also noted these safety issues (bolding mine):

…the Partnership for Safe Medicines found that product codes and paperwork accompanying foreign, non-Novo Nordisk sourced API presented for entry into our country contained numerous “red flags.” For example, shipments listed unlikely manufacturers, such as a major hotel chain, a fitness center, and a public school in Canada.

Novo Nordisk's independent test purchases have revealed that most semaglutide is being imported into the country from Chinese API suppliers and these findings also highlight the unlawful tactics employed by these entities to mislead consumers regarding the nature and origin of their products. Test purchases have identified mislabeled items such as “White Pigment” on packaging or “Adhesive” on import documents. Novo Nordisk has even obtained illegal shipments from China claiming to be “semaglutide” that are deceptively packaged as kitten food and facial masks. These imports into the country continue despite not meeting federal requirements for API shipments.

…so perhaps avoid compounded semaglutide.

Generic manufacturers’ responses seemed telling about where they source their drugs. Teva’s comment (which was unusually detailed and interesting to read), for example, requested that the EU, UK, Switzerland, Iceland, Canada, Mexico, Argentina, South Korea, and Israel be exempted from any tariffs. Aurobindo, a major generics manufacturer based in India, emphasized India’s longstanding positive relationship with the U.S.

What’s next?

Potential drug pricing fluctuations

In Europe, some companies are trying to use the threat of tariffs to lobby for higher drug prices in Europe, which would make them less dependent on the U.S. for profits.

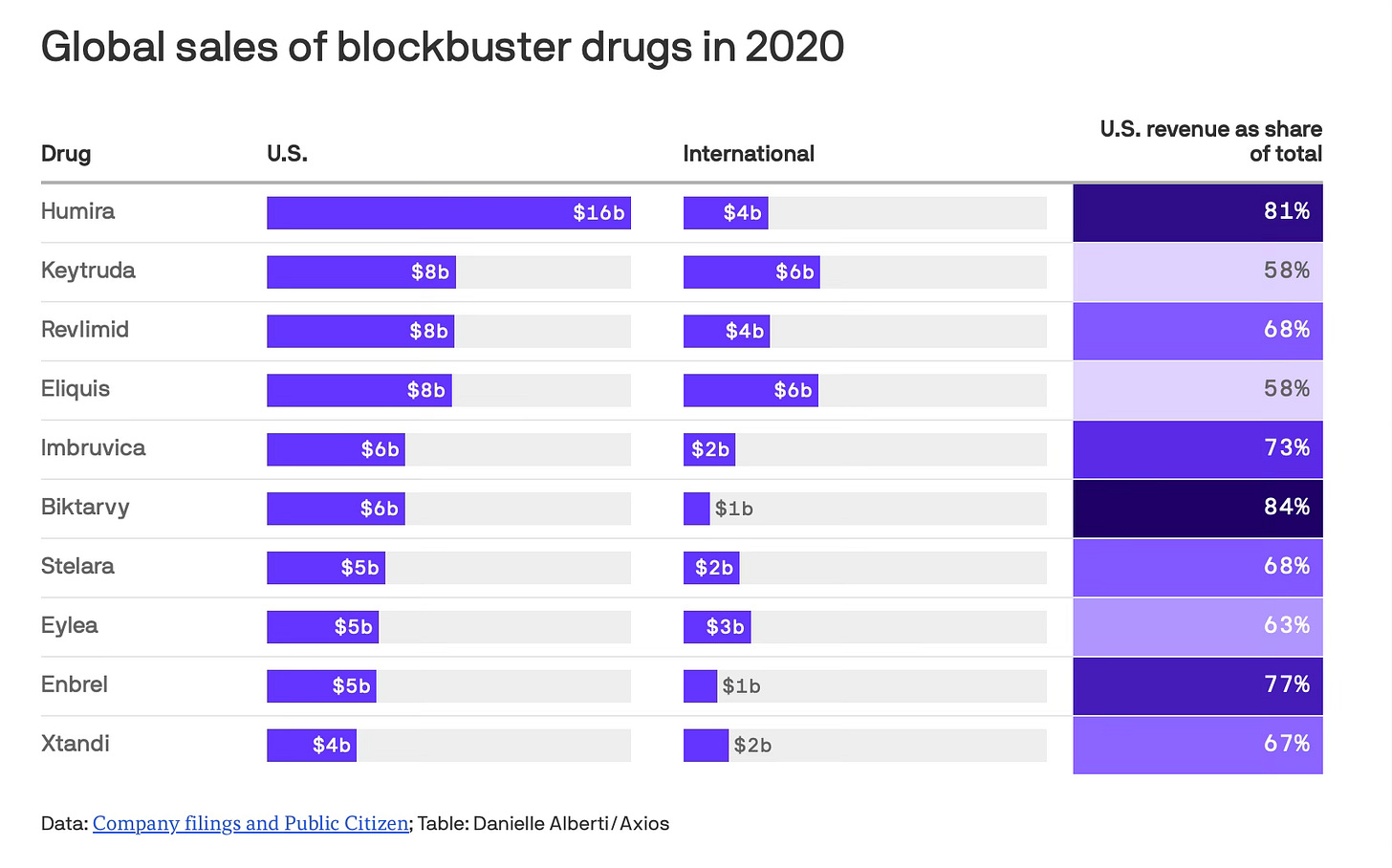

(Right now, European drug prices are capped, while U.S. prices are not. That means major pharma companies make a large percent of their profits from the U.S. market. An analysis by Public Citizen looked at the top 20 best-selling drugs worldwide and found that the U.S. market spent almost twice what the rest of the world combined did in 2020.)

Tariffs would change these dynamics, as would Trump’s executive order capping U.S. drug prices through a Most Favored Nation approach. This is a sweeping EO, the authority and enforcement are unclear, and companies aren’t yet jumping to action.

New infrastructure

On May 5, the Trump administration also released an executive order on building new pharmaceutical infrastructure in the U.S. The order is aimed at cutting through red tape for approval of domestic pharmaceutical plants: it directs the FDA to streamline the approval process and expand programs offering practical advice for new facilities, as well as directing the EPA to streamline the permitting process.

This might work? Companies are jumping over themselves to announce investments in the U.S. to appease Trump, with Roche investing $50 billion, Novartis pledging $23 billion, and J&J announcing $55 billion in just a small sampling of investments. But I’d also guess that there’s a calculus here. Building new facilities obviously requires a long lead time, and the Trump presidency has an expiration date. If they can get incentives to build new facilities, it might be worth their time. But they might just be trying to wait him out with announcements that go nowhere.

Takeaways

Tariffs would disrupt the pharmaceutical industry in dramatic and ultimately unpredictable ways. The comments submitted to the federal register all seem to acknowledge that the U.S. is indeed dependent on potentially hostile countries for drug production, especially for generics — but tariffs are a blunt tool that could cause disruptions in the short term unless paired with a faster building process in the U.S. or ally countries. It does seem like the administration is trying to allow for a faster building process, but it’s unclear if that’s possible to accomplish through executive orders alone.

I’ve never been less certain about how to quantify what our dependence on potentially hostile countries is! I had my go-to stats, pulled from Congressional testimony of FDA officials, but none of those numbers line up with individual companies’ letters. I need definitions, I need numbers, I’m not sure what’s going on (maybe no one does).

The companies who submitted comment really got creative with proposed alternatives, including multiple proposals for an expanded critical medicines stockpile. I’ve written before about how guaranteed government contracting is a good strategy to incentivize new antibiotic development, and I do think it’s a good idea for critical medicines — although these contracts should be tied to incentives for quality and strong supply chains regardless.

I have a well-documented suspicion of pharmaceutical manufacturers (actually, of the whole pharmaceutical value chain), but obviously we need them and their innovations. My approach toward pharma tariffs might be too sanguine, but I do believe that Operation Warp Speed taught us how dynamic this sector can be when it’s heavily incentivized, pushed in the right direction, and when (some) red tape is removed (obviously we need FDA inspections).

My real conclusion: there’s no way to know what will happen if and when pharmaceutical tariffs get implemented. Drug prices might go up (unless they’re capped). There might be shortages (until new facilities are built). New facilities might be built (but slowly). I do think we have a dangerous lack of knowledge about where our drugs are coming from and a dependence on potentially hostile countries. Are tariffs the fastest way to solve that? Maybe. Are they the most chaotic? Almost certainly.