Playing the game of specialty pharmacy

My extended analogy for all the tricks to maintain access

This week’s post is brought to you by my continued saga in the specialty pharmacy space. Aetna decided my case is not a high priority and so I won’t find out if they’ve accepted my doctor’s appeal until several weeks from now. Either way, Aetna wins; because Humira is an immunosuppressant, being off of it for a few weeks means my body has a good shot at making antibodies to it. Game recognizes game. (But I’ll be fine, there is a medical plan in place.)

The experience got me thinking about all the tricks patients use to maintain access to specialty meds, and how all of these programs add up to a confusing, opaque morass (which, of course, is the point).

So this post is about three major buckets of patient assistance available from drug companies, when they come into play, and what they mean for patients. Next week, I’ll be writing about what it would take to create something better—because the bar for something better is so low.

Pharma insurance specialists

Did you know Aetna (and other major insurers with blockbuster drugs) have dedicated insurance specialist teams? I didn’t.

In retrospect, it’s not surprising; each patient AbbVie can keep on Humira represents tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue a year. Each patient kept on Humira, in other words, pulls in enough revenue for AbbVie to more or less fund the full salary + benefits of the insurance specialist who kept them on the drug.

Add in the fact that Humira’s core patents expired in 2016, and that biosimilars finally hit the U.S. market in 2023, and AbbVie has an incentive to squeeze as much money out of their current Humira patients as possible.

I first realized the power of these insurance specialists when I called AbbVie and within—I’m not kidding—30 seconds flat, I had a Specialist™️ on the line. (Not for nothing, they were the nicest people I’ve interacted with the entire time, including my doctor.)

Michael, my insurance service specialist, took down some basic information and asked me to stay on the line while he called Aetna. “I’m so sorry, their call volumes are high during lunchtime,” he said. I started to brace myself for an hour-long wait, which is approximately how long it took when I last called Aetna. Instead, he asked, apologetically, if I could hang on for 10 minutes. By this point I had set aside my skepticism and was thinking to myself, anything for you, Michael.

In other words, insurance specialists at drug companies have more or less a direct line to major insurers. It’s not a conspiracy (that would require a level of coordination I know specialty pharmacy isn’t capable of), it’s more of a frustrating game that we all have to play because of the way the system is currently structured. Aetna has to deny expensive medicine claims to keep expenditures down. AbbVie has to fight back to keep their revenue high. They’ve both hired people whose jobs are explicitly to do those things—and the patients just have to play along.

Patient-assistance programs (PAPs)

If specialty drug pricing is a game, patient-assistance programs are the secret cheat codes.

PAPs typically provide cost assistance for the uninsured and/or copay assistance for the insured. The eligibility requirements vary. A study published in Health Affairs in 2009 found that 4% of surveyed PAPs disclosed how many patients they helped, and only half disclosed their income eligibility criteria. (Needless to say, these are at best a paltry substitute for real access to care.)

Depending on the drug and the manufacturer, these programs exist to:

Keep patients on pricier brand-name drugs when a generic alternative is available, or

To provide the companies with some political cover for their high drug prices.

The Humira PAP, for example, falls into the second category now, but it will pivot to the first category in two years, when biosimilar competitors come on the market.

PAPs are also emblematic of the challenges of the broader healthcare system because you have to know they exist before you can take advantage of them. It’s an additional layer of complexity that only more privileged patients know about.

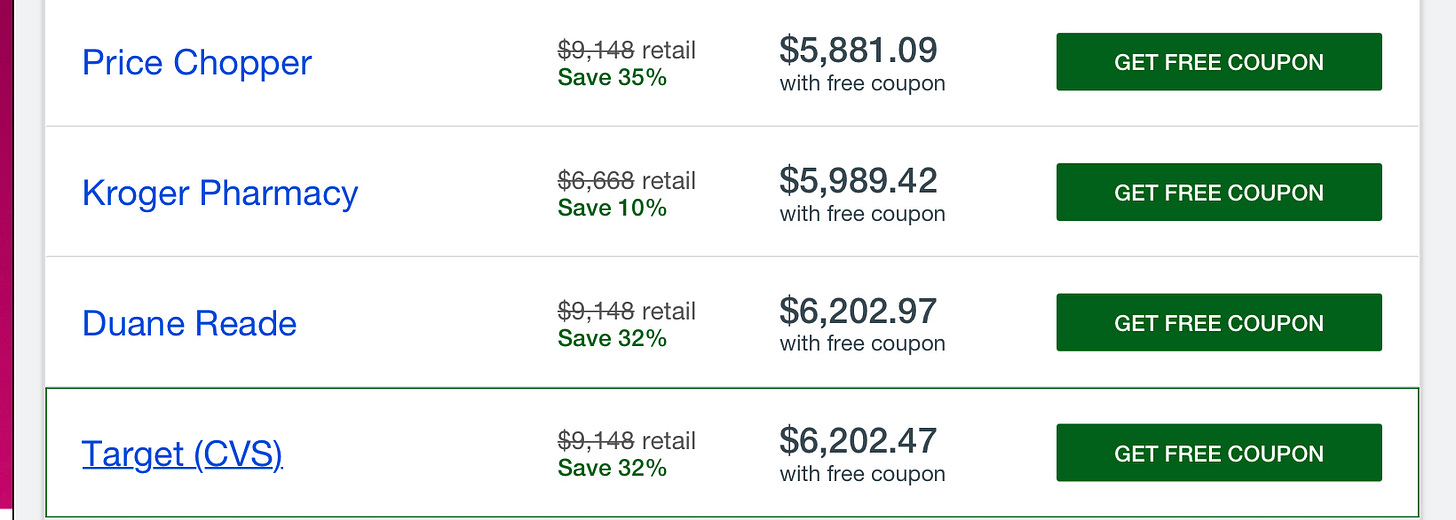

GoodRx

To continue my game analogy: GoodRx is the website that shows you how to find cheat codes (which can be PAP coupons, other manufacturer coupons, or pharmacy discounts). The business model is simple but powerful, earning them a $1 billion+ IPO.

Of course, GoodRx can’t make every drug affordable.

Patient advocacy groups

Patient advocacy groups are your teammates in the specialty pharmacy game, although teammates you may start to suspect are funded by the game company to keep you playing longer (does that happen in gaming? I’m stretching this analogy as far as it will go).

Patient advocacy groups are typically the first stop that a patient newly diagnosed with a disease makes. These groups may provide additional information, support groups, and legislative advocacy opportunities. They’re also largely funded by pharma.

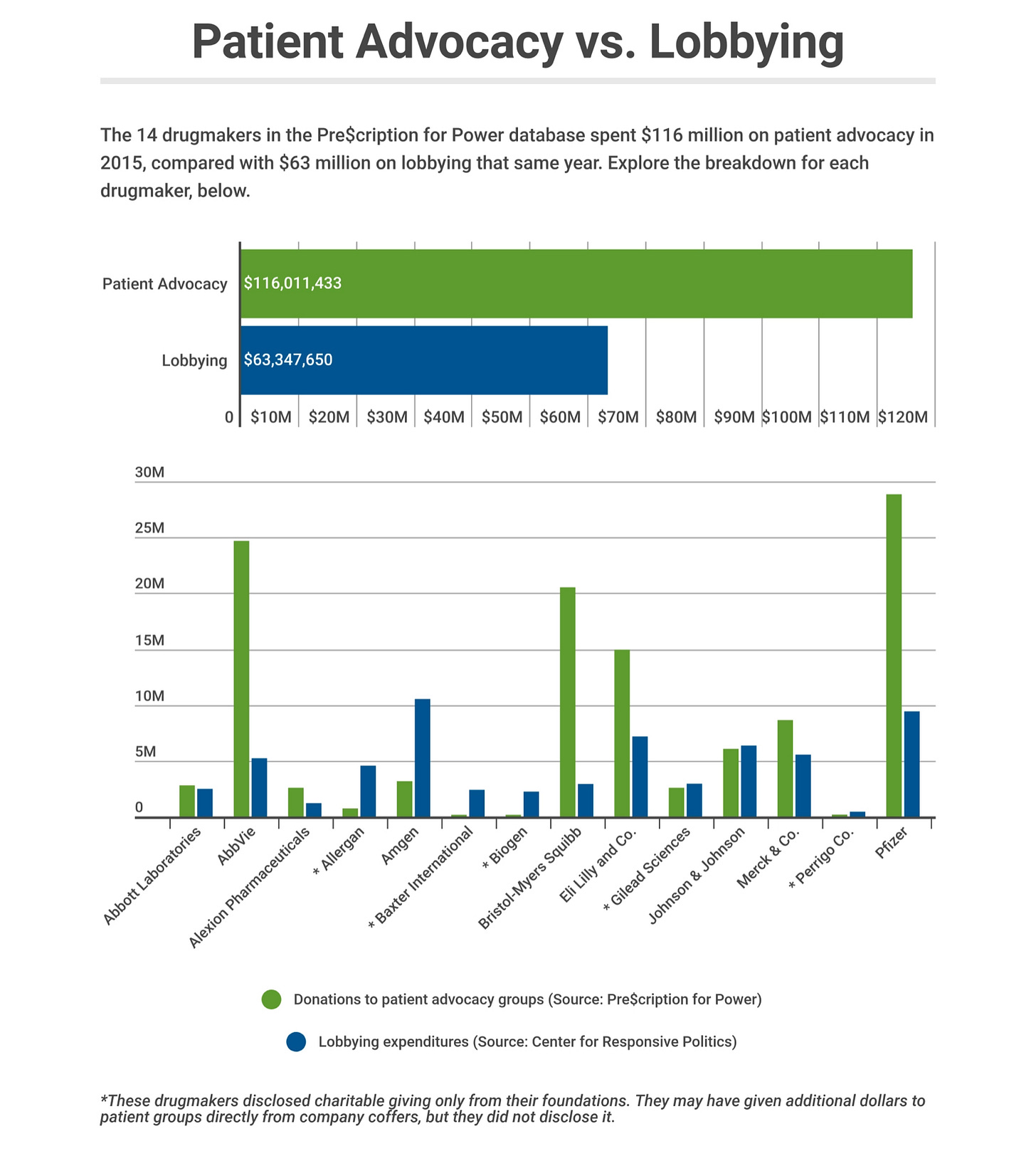

Kaiser Health News maintains a database tracking the reported donations of large pharmaceutical companies to patient advocacy groups. In 2018, KHN reported that donations were far surpassing drug companies’ spending on lobbying.

This sounds good, and some or most of that money goes to patient education and support. But patient advocacy groups also provide a layer of humanity to drug companies’ lobbying efforts, in ways that can start to feel suspect. For example, some patient advocacy groups strongly oppose biosimilars on the dubious grounds (in my opinion) of safety.

One of the most blatant examples of how money can warp the goals of these entities, although not pharmaceutical, was in California a few years ago. The American Kidney Fund, a group that helps connect end stage renal disease patients with resources and provides them with stipends to cover private insurance premiums, is almost entirely funded by DaVita and Fresenius, the duopoly dialysis providers in the U.S.

Why would they want to cover private insurance premiums? Because Medicare, which people with ESRD automatically qualify for, reimburses far less for dialysis than private insurance. Quoting from the American Prospect:

DaVita's own presentation at the 2018 J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference tells the story. While 90 percent of treatments come from patients on government plans, accounting for 60 to 70 percent of revenue, a startling 115 percent of its profits come from patients with private insurance, which companies like DaVita and Fresenius can bill for four times as much.

This arrangement became a national story when a bill was introduced in California that would cap the amount dialysis providers could charge private insurance, and which would disallow non-medical entities from steering patients into different coverage options. DaVita and Fresenius threatened to pull out of the state and stop covering patients’ premiums, dropping all of their end-stage renal disease patients off of insurance. (The bill ultimately passed, but a state court temporarily halted its implementation in early 2020.)

Conclusion

I’ve spent a lot of time talking about the problems with the specialty pharmacy space. But where do we go from here? Next week’s post is about why building a specialty pharmacy disrupter is so challenging—and what I think needs to happen to see one come to fruition.

Also, thank you to everyone who wrote me back after the last post, I really loved hearing your thoughts. Similarly, if you have any thoughts about PAPs, drug pricing, or how to improve the specialty pharmacy model, let me know!

This information shouldn’t be taken as investment advice (obviously), and the opinions expressed are entirely my own, not representative of my employer or anyone else.

I really want you to talk to my wife as she is in specialty pharmacy at CVS health... was in retail so this is a whole new world. If you ever need anything let me know!