Before Memorial Day, I wrote about the direct contracting models that some provider groups have started to experiment with. I also ended that newsletter saying I wanted to talk more about primary care capitation.

Primary care providers have long experimented with different models that have a capitation-lite element, particularly services like concierge or executive medicine that target wealthier patients.

But now, CMS is more actively encouraging providers toward advanced payment models. The agency recently introduced two different payment models: Primary Care First (PCF) and Direct Contracting. You can read more about the nuances in this CMS explainer, but both models incentivize value-based primary care.

One note: the third option under Direct Contracting is indefinitely paused, and I’ve heard rumors that the second option under PCF is also likely to be halted.

The ideal primary care capitation model

At the same time, the number of doctors—especially primary care physicians—calling for some kind of value-based care seems to be increasing. In an article published a few weeks ago in JAMA, Drs. Zeke Emanuel, Farzad Mostashari, and Amol Navanthe wrote about primary care capitation.

They note (emphasis mine) that “based on pandemic experience, 75% of 765 clinicians polled in a March 2021 survey do not believe FFS [fee-for-service] should account for the majority of primary care payment.”

In other words, 75% of polled primary care clinicians believe that some kind of capitated or value-based payment model should be the majority of primary care revenue.

As the JAMA article notes, the COVID-19 pandemic is heavily tied up in this push for value-based payment models. Many primary care doctors—as well as other doctors in private practice, and those who otherwise saw volumes drop during the pandemic—are now looking for a guaranteed revenue flow.

It doesn’t hurt that capitated payments would remain the same regardless of whether doctors manage their patients via telemedicine, email, or with more traditional in-person visits. This level of certainty would allow doctors to invest more in telehealth workflows and alternate staffing models that fit the needs of their patients, rather than waiting anxiously to see what lawmakers and regulators do about telehealth reimbursement.

And, of course, advanced payment models incentivize more provider attention to relieving (as much as possible) some of the socioeconomic burden that some patients may struggle with. After my last newsletter, I talked to a friend who runs a direct contracting entity. She told me that the capitation her DCE receives allows it to take huge steps in altering its staffing model, prioritizing social workers and care coordinators. According to my friend, entities using the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), an older value-based care model, would have to be unusually well-funded to feel the same magnitude of incentive to shift the workflow and staffing model.

Shifts in the market

The new CMS models are causing shifts in the market in another way. The models allow DCEs to align anyone (with the patient’s permission) to a PCP within the DCE network and receive the capitated payments. There’s suddenly an incentive to have as many patients aligned with your entity as possible.

This seems to be true for both traditional entities like major insurers (Optum is rumored to be acquiring Landmark, with its share of traditional Medicare patients) and smaller startups (Oak Street and Iora Health are scaling quickly to take advantage of the new models).

Making this game of musical chairs even more complicated, CMS recently stopped accepting further applications to the Direct Contracting program, leaving entities that were preparing to apply without that option. Now some entities are trying to contract with existing DCEs to align their patients to the DCE and presumably share in capitation revenue.

The challenges of cost savings in primary care

Despite the industry attention, actually saving money with value-based payments in primary care may prove difficult.

In a 2017 post written by Kevin O’Leary (fun marker of time: in Part I, he mentions a new startup that just spun out of Google named Cityblock), he writes about new models of primary care, and what these new models will have to accomplish to see cost savings.

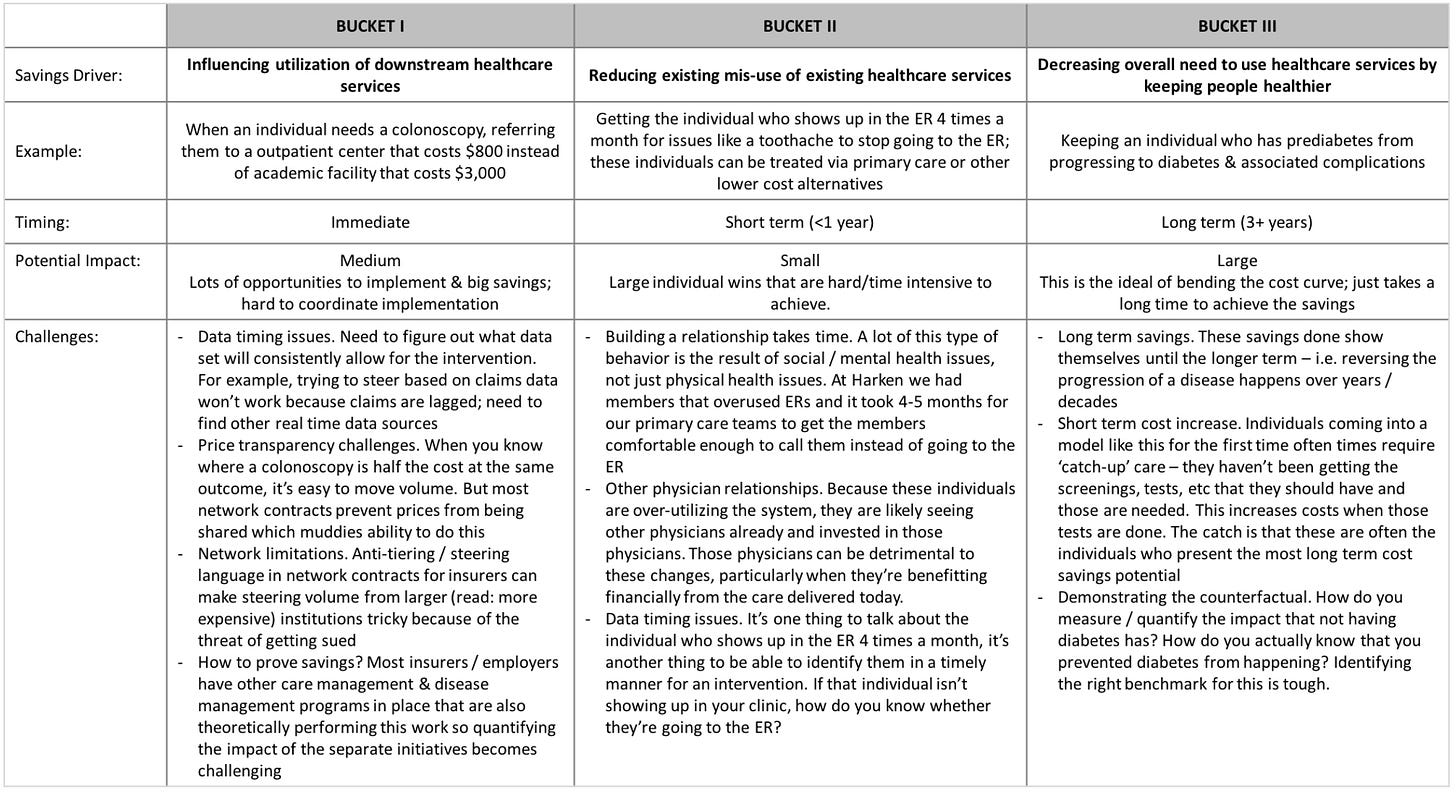

This chart is particularly helpful:

Primary care can drive savings in a number of ways: influencing utilization of downstream services (medium difficulty, medium potential impact), reducing existing misuse of healthcare services (medium difficulty, low potential impact), and keeping patients healthier and thus reducing their healthcare expenditures over time (high difficulty, high potential impact).

As the chart points out, Bucket III, or keeping patients healthier and therefore decreasing their need for services over a long time horizon, has the greatest potential to bend the cost curve—but it also requires tracking patients over several years at least. The current healthcare system is so fragmented (particularly from a data standpoint) that tracking patients is very difficult.

It’s also unclear to me that there’s any safeguard in most value-based care models against primary care providers shifting their patients’ pricier needs outside the primary care entity and thus avoiding the cost being associated with the PCP (without actually saving any money for the overall healthcare system).1

In other words, the fragmentation of the system, the challenges of longitudinally keeping track of patients, and the frustrations of trying to influence patient behavior make it very difficult for primary care practices—even innovative ones with advanced payment models—to achieve savings.

It remains to be seen whether the latest CMS-driven shift toward value-based primary care overcomes these issues.

Conclusion

I’m very excited to see how this turns out. CMS is incentivizing some big moves—and the system certainly needed to be shaken up.

From my point of view, it seems like one potential outcome is that large insurers like Optum manage to align most of the participating traditional Medicare patients with Optum entities, leaving faster-moving, more innovative practices locked outside the new models. There might be some cost savings (which would accrue to Optum, in this scenario) but otherwise the provision of healthcare isn’t dramatically changed.

The other possibility is that this switch to value-based care genuinely incentivizes more primary care providers to remain independent, nimble, and innovative, that these practices hire more social workers and therapists, and that CMS realizes some cost savings but that the majority of the shift is in better patient care. Which would be a huge development.

As always, reply to this email or leave a comment if you agree, disagree, or have additional insight—such a (potentially) big shift in how we do primary care deserves a lot more discussion.

This information shouldn’t be taken as investment advice (obviously), and the opinions expressed are entirely my own, not representative of my employer or anyone else.

This, I imagine, was the drive behind CMS’s Geo Model, which tied together all participating providers within a geographic location, making it more difficult to cost-shift patients to other providers. However, the Geo Model is indefinitely paused.