Quest, LabCorp, and slow COVID-19 results

The two corporations are more focused on expanding market power than expanding testing capacity

This post marks a month since I started this newsletter. Thank you all for being a part of it! If you think there’s a topic I should cover, reply to this email or leave a comment below.

On Wednesday, July 22nd, Montana announced that it was firing Quest Diagnostics, one of the largest lab testing companies in the country, from its COVID-19 testing program. Quest Diagnostics had been slow to return results to patients, rendering the tests useless. Further, the corporation had told state officials it was at capacity and would be unable to process any more tests for another two to three weeks. “We don’t want to be left high and dry again in the event that the national demand for testing puts a state like ours onto the back burner,” Governor Steve Bullock said.

The next day, Quest Diagnostics held its second-quarter earnings call, during which CEO Steve Rusckowski discussed the corporation’s pandemic strategy. It wouldn’t be to radically increase the efficiency of testing or to find new ways of winning back customers like the state of Montana; instead, it was to buy up the competition. Rusckowski noted that “smaller regional laboratories have had…challenges,” resulting in “more opportunities for talking acquisitions.” Quest’s priorities are clear—acquire more laboratories, rather than focus on testing.

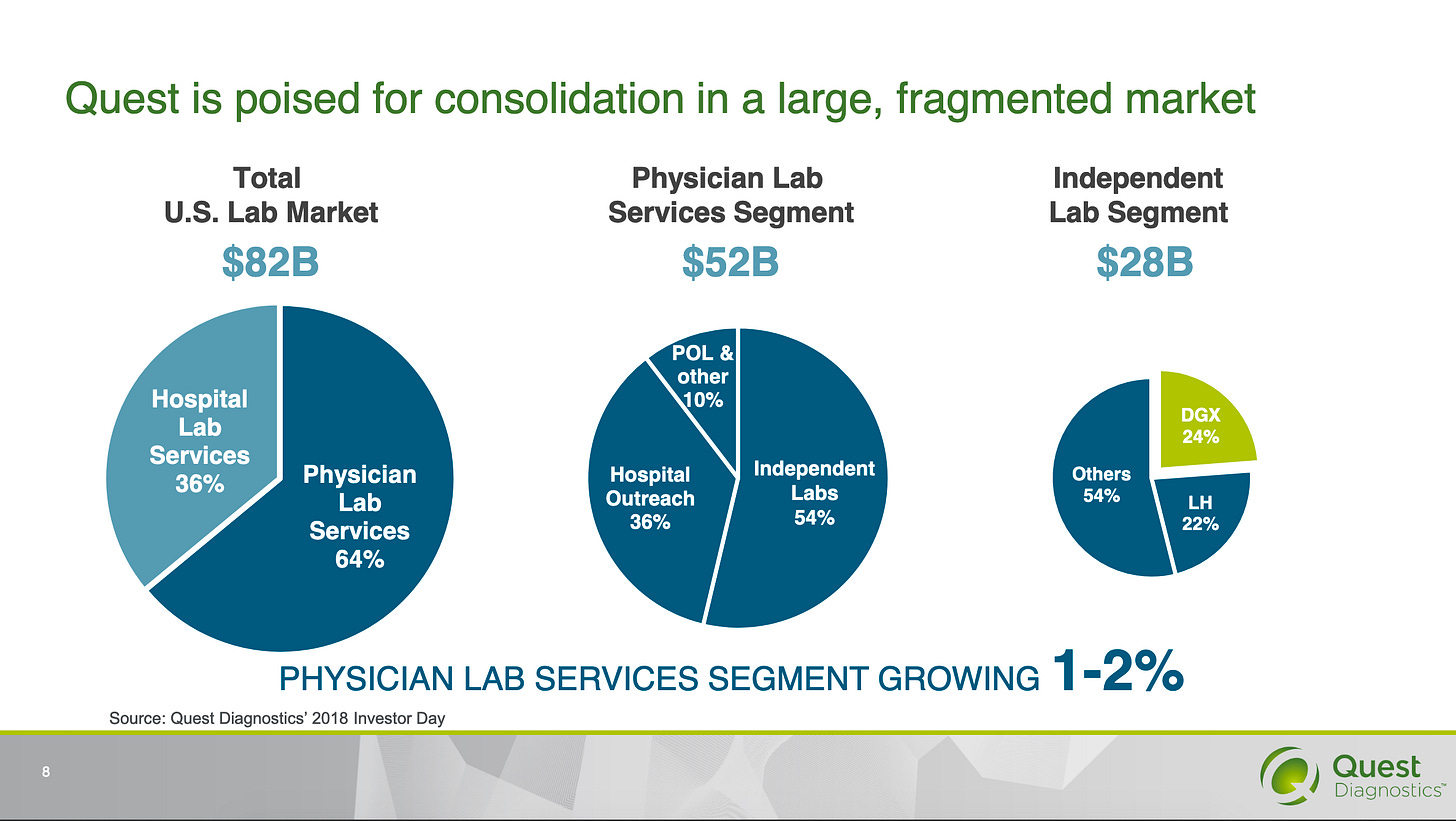

Quest, and its major competitor LabCorp, can treat their customers with disdain because they have substantial market power. Consolidation is their strategy. Below, for example, is a slide from a recent presentation to investors (Quest’s stock symbol is DGX and LabCorp’s is LH).

The lab sector in the U.S. does not, at first glance, seem to be riddled with monopoly problems. It’s fairly easy to set up a lab, and testing is cheap. Indeed, it doesn’t even appear to be that concentrated a sector: Quest and its rival, LabCorp, hold just under half of the independent lab testing market in the US. For now, most hospitals have their own labs (although Quest’s Rusckowski is trying hard to change this), keeping Quest and LabCorp in the outpatient space.

And while there are some economies of scale for laboratory work—fancier machines are able to run more samples, for example, and the two corporations utilize aircraft to carry their blood samples to huge, automated testing centers—Quest and LabCorp make a large portion of their revenue on tests that could be done by any well-trained technician with the right equipment. (Quest and LabCorp treat their employees as commodities too. The average salary for a lab technician at Quest is $15. At LabCorp, it’s $17.)

Peer a bit closer, though, and it becomes clear that these companies wield a lot of power. Lab markets are dependent on geography (blood has to be physically at a lab to be tested), meaning Quest and LabCorp can dominate local markets even though their share of the national market seems low. Perhaps because the market seems less concentrated than it is, Quest and LabCorp have largely skirted by regulators. But their power seems set to grow unless regulators intervene.

Exclusionary tactics

Quest estimates that it serves a third of US adults every year, and fully half of the US adult population every three years. With 7,000 patient access points (approximately 2,300 of these access points are lab locations and 4,700 are phlebotomists in physicians’ offices), that’s not a surprise. LabCorp boasts similar numbers, with 2,000 patient labs and more than 6,000 in-office phlebotomists.

These two corporations, running commoditized tests, have created barriers to entry based on contractual arrangements with insurers. Before 2019, these networks were strict; if you were an Aetna member, for example, you only had in-network access to Quest labs. This allowed Quest and LabCorp to segment the outpatient network. If someone wanted to start an independent lab, it was difficult to get customers because insurers already had exclusive deals with Quest or LabCorp. Because insurers have become so large themselves, the lab diagnostics market is a game almost exclusively played by national giants.

Quest has also engaged in predatory schemes to knock competitors out of the market. In 2015, three patients sued Quest, alleging that Quest colluded with Aetna and Blue Shield of California. The lawsuit alleged that Quest offered the two insurers a discount if they removed competitor labs from their networks, making it more expensive for patients to use those labs. At least one of the competitors went bankrupt. This arrangement, a type of predatory rebate, has traditionally been considered an antitrust violation, though enforcers haven’t been assertive in enforcing this area of law.

Quest and LabCorp also dominate by buying up competitors. Quest used to be part of Corning Glass Works, a maker of glassware and fiber-optics, until it was spun out into a separate entity on the stock exchange in 1997. As an independent corporation, Quest became an aggressive acquirer of other entities. In the early 1980s, the Reagan administration relaxed merger laws, and in the 1990s consolidation in health care industry exploded. Quest took full advantage, with the following mergers growing the corporation into its current behemoth size:

1997, Diagnostic Medical Laboratory, Inc. (DML)

1999, SmithKline Beecham Clinical Labs

2001, MedPlus, Inc.

2002, American Medical Laboratories and affiliate LabPortal, for $500 million in cash

2003, Unilab Corporation, for approx. $800 million

2005, LabOne, for approx. $934 million

2006, Focus Diagnostics, approx. $185 million in cash

2007, Hemocue

2007, AmeriPath, cancer diagnostic testing

2011, Athena Diagnostics, the leading provider of neurological diagnostic testing

2011, Celera Corporation, which had sequenced the human genome during the Human Genome Project

2014, Solstas Lab Partners Group

2014, Summit Health

2017: Cleveland HeartLab

2018: Oxford Immunotec

LabCorp has a similar beginning, with a similar list of acquisitions. Because most bloodwork is a commodity, LabCorp and Quest rely on acquisitions and exclusive dealing to maintain their share of the market.

The last two years, perhaps fed up with opaque and rising lab prices, insurers began negotiating more aggressively with the two giants. Insurers were (and are) transitioning to value-based care models—meaning they gauge success less by volume of care and more by appropriate care—a paradigm that encourages more competition in the lab space. In 2019, Blue Cross Blue Shield of New Jersey ended its exclusive deal with LabCorp by signing with Quest (except for BCBSNJ’s 900,000 Medicaid patients, who still only have access to LabCorp). United Health Group signed with Quest as well, ending LabCorp’s monopoly over UHG patients. And Aetna signed with LabCorp, ending Quest’s control over Aetna patients.

The labs’ response to this harder line was not, however, to find ways of competing more effectively, but to look to new areas in which to gain market power. One area in which they’ve focused is inpatient lab testing, historically the provenance of individual hospitals (though both Labcorp and Quest have had some deals with hospitals for decades). Another is independent labs weakened by the pandemic shutdown.

COVID-19 testing

But while LabCorp and Quest aggressively look to acquire regional and hospital laboratories, they are also slow-walking the need to expand COVID-19 testing. The testing effort is undeniably unprecedented, and a lack of reagants and testing supplies (which is what LabCorp and Quest have blamed) is part of the problem. But that’s not the whole story. In Montana, other, smaller labs are producing much faster results. As Kaiser Health News noted in July, Walmart uses both Quest and a smaller company called eTrueNorth to process its COVID-19 tests; Quest’s turn-around time is a week, while eTrueNorth’s is three to five days.

Rather than work through the complicated logistics of testing, LabCorp and Quest have preferred to find places to monopolize. There’s a cap on the revenue to be made in expanding testing; the CARES Act restricts commercial laboratories from billing patients beyond what their insurers cover for COVID-19 testing. But if the two corporations can expand their market power, their ability to raise labwork prices in the future outstrips potential COVID-19 testing revenue.

(Relatedly, there’s precedent for the two corporations to overbill—they’re both the subject of class action lawsuits filed in 2017 alleging “fees far in excess of the market rates.” That same year, LabCorp spent $338 million on stock buybacks. Quest spent $465 million.)

In a recent interview with Wired, Bill Gates noted that the COVID-19 testing incentive structure, which reimburses for tests at the same rate regardless of when the test results come in, allows the major diagnostics companies to deprioritize rapid results. “If you don’t care how late the date is and you reimburse at the same level,” said Gates, “of course [the lab corporations are] going to take every customer. Because they are making ridiculous money, and it’s mostly rich people that are getting access to that.”

Jon Stokes, the founder of Ars Technica, believes there’s a darker answer to the mess of COVID-19 testing. Stokes noted on Twitter that he believes the simplest explanation for some of the reports of wonky test occurrences—like people getting test results even when they weren’t tested—is corporate fraud.

But at the same time it’s possibly engaging in fraud and definitely not expanding adequate testing capacity, LabCorp is trying to monetize office workers’ return. In July, it announced a partnership with real estate corporation JLL to provide “a comprehensive suite of employee wellness services,” including temperature screening, virus testing, and flu vaccinations.

Rather than prioritizing fast test results, the two corporations are focused on monetizing the pandemic via “strategic partnerships” and buying up competing hospital and regional labs.

The threat of large corporations using the pandemic to make easy targets of weakened businesses is real, across industry sectors. What’s particularly frustrating about LabCorp and Quest is that they seem to be pursuing these monetization goals instead of throwing their considerable weight behind a national COVID-19 testing effort. It should have been monumentally embarrassing for the CEO of the largest testing company in America to be fired by the state of Montana in the midst of a pandemic. But on his earnings call the next day, it wasn’t even mentioned. And that’s because we’ve set up our laws to have our corporate leaders focus on taking advantage of the pandemic to expand their market power, instead of addressing the disease itself.

Many thanks to Matt Stoller (whose newsletter Big is also on Substack and very worth reading) for his edits.