The banality of evil: the prior authorization process

Or: if we can’t figure this out, how do we ever figure out value-based care?

Sorry, I can’t stop talking about specialty pharmacy. There’s always more to say! This week, the prior authorization process, motivated by a personal, ongoing experience.

Before insurers cover a procedure or medication, many of them have a prior authorization process, where they require doctors to apply (beg) for a drug or procedure to be covered.

I’ve become intimately familiar with this process over the last few weeks. Since I switched jobs, my insurance policy and ID number slightly changed, although I’m still under the Aetna umbrella. But I may as well be dealing with an entirely different insurer; Aetna is now denying coverage for the Humira I’ve been on for years.

Throughout the process, I’ve been struck by how impossible to navigate it would be if I were any less privileged and health literate. It’s complicated, confusing, and an enormous waste of time.

First, I tried to re-order Humira (they won’t send me more than a month’s supply at a time) through the CVS Specialty Pharmacy app (readers who have been with me for a while are familiar with my dislike for CVS Specialty and its app that never, ever does what it’s supposed to). It, unusually, seemed to go through. I waited for the Humira to show up, only noticing a week later that it never had. I called CVS Specialty, where a nice woman told me that, for some reason, my order had been terminated and flagged. She didn’t know why. Sigh.

Next I called Aetna. After solidly 45 minutes, we figured out that my insurance number had changed, and although I swear I gave the new number to Aetna (never mind that Aetna and CVS Specialty are one entity, and that I had been with Aetna...the whole time), I gave it to them again.

But THAT triggered a cascade requiring my doctor to resubmit a prior authorization. The Aetna people seemed appalled that I had run out of medication, so they told me they’d accept a verbal authorization from my doctor if I could get the doctor to call within the hour. At 4pm on a Friday. Needless to say, I couldn’t even make it through my doctor’s phone tree before the time was up.

So then, several business days later (during which I sent my provider’s office my insurance information no fewer than 3 times, including email, fax, and verbally—I don’t know how they kept losing it), my doctor finally submitted a prior authorization.

Aetna, my friends, denied the claim.

So here we are. I haven’t had access to Humira for a few weeks, no one seems particularly concerned by it, and I’m just floating along until something happens. I have an expired syringe sitting on my dresser that I might just use and see what happens. I set myself a recurring reminder to call my doctor every other day to check on the progress. Every other day I leave a voicemail, and then I get a call maybe 72 hours later from an administrator telling me that my doctor is working on an appeal. The legal language is funny given how utterly arbitrary the process is.

I’ve said this before—and I’m certainly not the first—but so much of the healthcare system in general and the chronic care system in particular is death by a thousand cuts, banal waste for everyone. My doctor has hundreds of other patients, the Aetna call center people have no insight into the claims denial process, and the claims people have no idea that I’ve been getting Humira via the Aetna/CVS Specialty system for years. CVS Specialty is just always confused.

How did we get here?

The more time I spend on the phone with all of the stakeholders in the process, the more I’m completely bamboozled by how much waste it creates. The whole process is manual, and it’s tied together by the patient (or, I suppose, whoever decides to spend hours on the phone forcing everyone to communicate with each other). My situation is far from unique. As of 2018, 88% of prior authorizations were happening via phone or fax.

If anything, it’s a testament to how expensive some procedures and medications are, if the prior authorization process still saves money. I can’t find great data, although a relatively narrow study published in 2018 found that prior authorizations lowered prescription drug costs generally (but no word on administrator costs). On the physician side, prior authorizations cost approximately $2,000 to nearly $3,500 per physician FTE per year. Compared to all of the other time physicians spend interacting with insurers (worth a total of nearly $83,000 according to one 2011 study), prior authorizations seem to take up a relatively minor chunk of physician time. Maybe this is why no one’s particularly motivated to change the prior authorization status quo.

Now what?

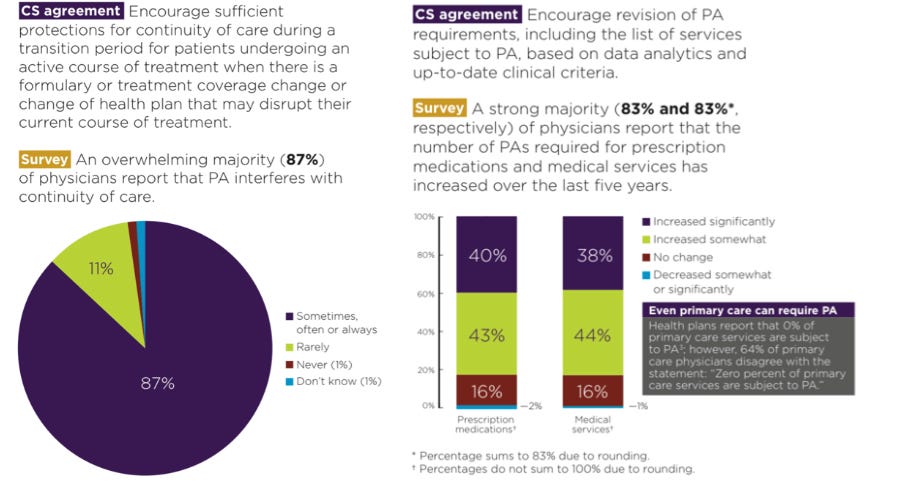

Three years ago, the American Medical Association and an assortment of other major stakeholders (America’s Health Insurance Plans, American Pharmacists’ Association, and more) across the healthcare system released a consensus statement calling for reform to the prior authorization process. Among other things, they called for a pivot to electronic prior authorizations, minimizing prior authorizations for patients merely experiencing a formulary or policy number change, and regular prior authorization program review and volume adjustments.

Although the consensus statement seems like a positive step forward, it really wasn’t implemented. In 2020, the AMA surveyed 1,000 practicing physicians on whether they’d seen facets of the consensus reforms take place in their practices. The answer was no.

The consensus statement lays out what a better system would look like. It’s still banal and complicated, but it would strongly encourage the use of electronic prior authorization forms, require insurance companies to clearly explain why they’re denying a claim, and would be more narrowly focused on the most expensive and unproven procedures and treatments. The process could happen a lot faster, and it would require less of the physician.

The fact that it hasn’t been implemented, however, makes me think that chronic care patients have a long slog ahead of them (relatedly, this is why I’m personally betting on virtual specialized chronic care—if you can create a new system, it’s easier to implement reforms that all agree are needed, but which will take years or decades in the traditional system).

Finally, the frustrations of the prior authorization process make me question everything I know about value-based care. Theoretically, Aetna should be incentivized to cover medications that do a great job of keeping my expensive chronic condition managed; I’ll cost less long-term. The fact that I’ve been with Aetna for years means that they’re probably reaping those cost benefits now and in an ongoing way. But the insurer seems totally incapable of even tracking that, let alone making proactive value-based decisions. I’m quite sure they’re not the only one. So what does this mean for value-based care? If you have thoughts, comment below or reply to this email—I’d love to hear them.

This information shouldn’t be taken as investment advice (obviously), and the opinions expressed are entirely my own, not representative of my employer or anyone else.