It was hard to pull myself away from the vaccine news cycle to write this, but I feel like my value add is in talking about systems—and journalists seem to have the vaccine roll-out process covered.

Instead, I’m turning to a topic that I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the last few weeks: specialty pharmacy, and why it’s an uphill battle to innovate in the space.

This started because of an idea I had. What if there was a specialty pharmacy that catered to Crohn’s disease, or IBD, or autoimmune diseases? What if the phones were managed by real, trained people, rather than an electronic phone tree? What if the pharmacy provided patient resources, like watchable videos explaining how to inject or otherwise take the specialty medication?

I asked a few smart health tech people in my network, some of whom have helped launch pharmacy businesses or worked at them: what would it take to launch a consumer-focused specialty pharmacy?

Well—the answer is frustrating. The specialty pharmacy market is dominated by just a few players who have largely rolled up the space. The health tech people, while they thought my idea was a good one, pointed out the enormous barriers to getting such a business off the ground. But if someone could get this off the ground, it wouldn’t take that many patients to be a success, because specialty pharmacies make money as a margin of high-cost drugs.

Anyway, if you have any suggestions or comments on this, reply to this email or comment below. The rest of this newsletter is about what the market is, and the current barriers to innovation.

The existing system is terrible

Specialty pharmacies are a subset of the overall pharmacy market, and they handle/sell/deliver drugs that require a little more attention than the cheap antibiotics you can get at a retail CVS location. Specialty pharmacy drugs like Humira or chemotherapy drugs have to be specially refrigerated and managed, then delivered to either a hospital infusion center or to a patient’s home.

Specialty drugs also tend to be quite a bit more expensive than standard drugs—like thousands of dollars more expensive. Because pharmacies more or less make their money as a margin of the drug they sell (a margin that can be as slim as 5% of the drug), specialty pharmacies can be lucrative businesses even if they cater to a relatively small population. After all, 5% of a $100,000 yearly spend on an immunotherapy drug, for example, is still $5,000.

What grabbed my attention is that, despite this influx of money, the patient experience remains simply terrible.

As a Humira user, every month I have to call into a phone tree, suffer the Muzak, talk to a bored call center representative who knows nothing about Crohn’s disease or Humira, and then get patched through to a pharmacist to confirm that, yes, I would like another month of this unnecessarily expensive but effective medication. I usually have to budget 20-45 minutes each month, just for this one interaction.

And I’m certainly not the only person who’s had this experience.

These pharmacies make so much money…why are they so terrible?

Specialty pharmacy: a calcified market

Those who follow my organization’s work and my colleague Matt Stoller’s newsletter will recognize the pharmacy industry as having all the hallmarks of a highly concentrated and calcified system: limited or no consumer choice, terrible consumer service, confusing interface, high prices. But you still might be surprised at just how concentrated it is.

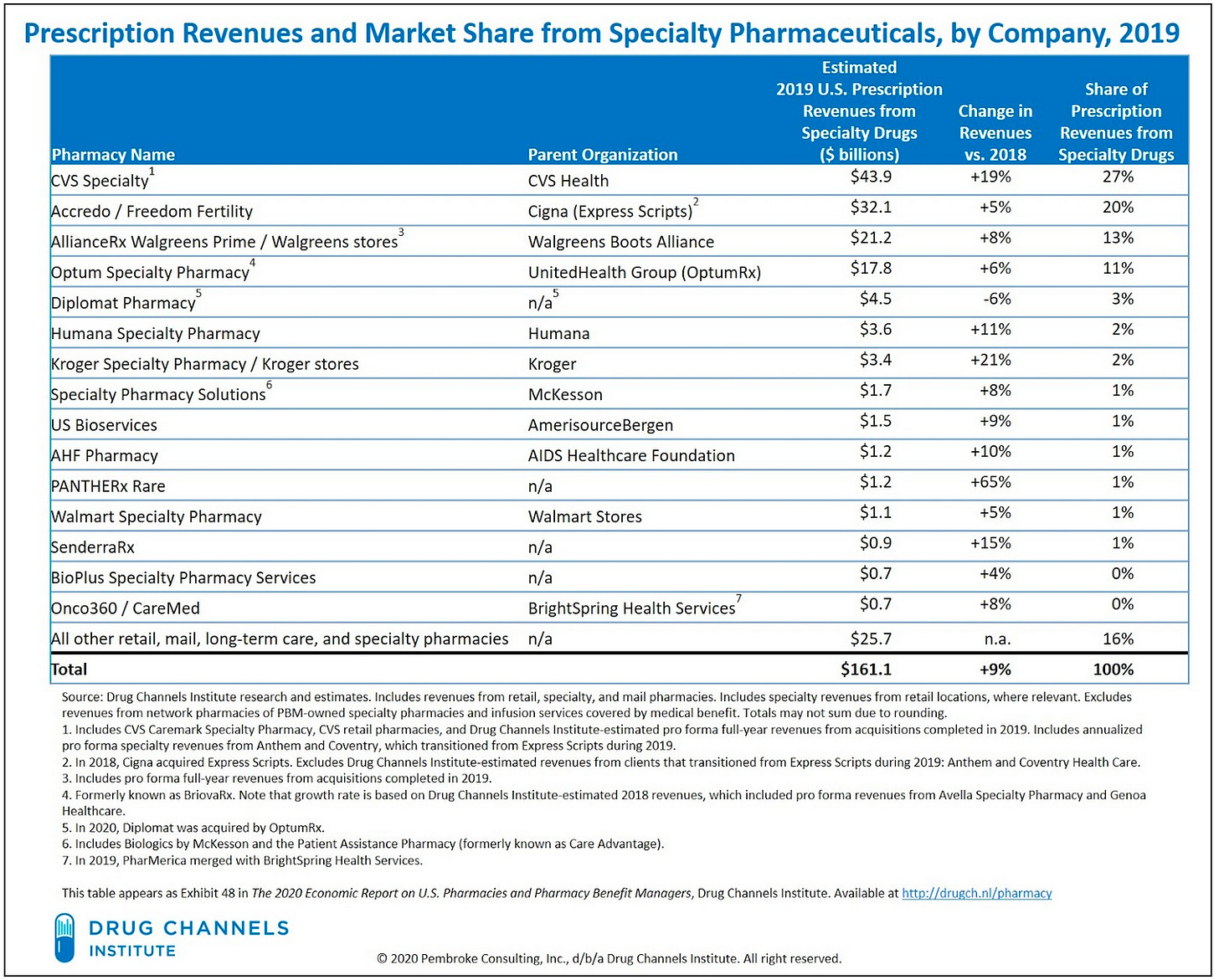

As of 2019, the top 5 specialty pharmacies held an estimated 74% of the market. This consolidation has only gone up since then; Optum has since acquired Diplomat, which was number 5. It’s also worth noting that nearly all of the top specialty pharmacies are owned by a parent company that is, in turn, associated with an insurer or other large entity.

Source: https://www.drugchannels.net/2020/04/the-top-15-specialty-pharmacies-of-2019.html

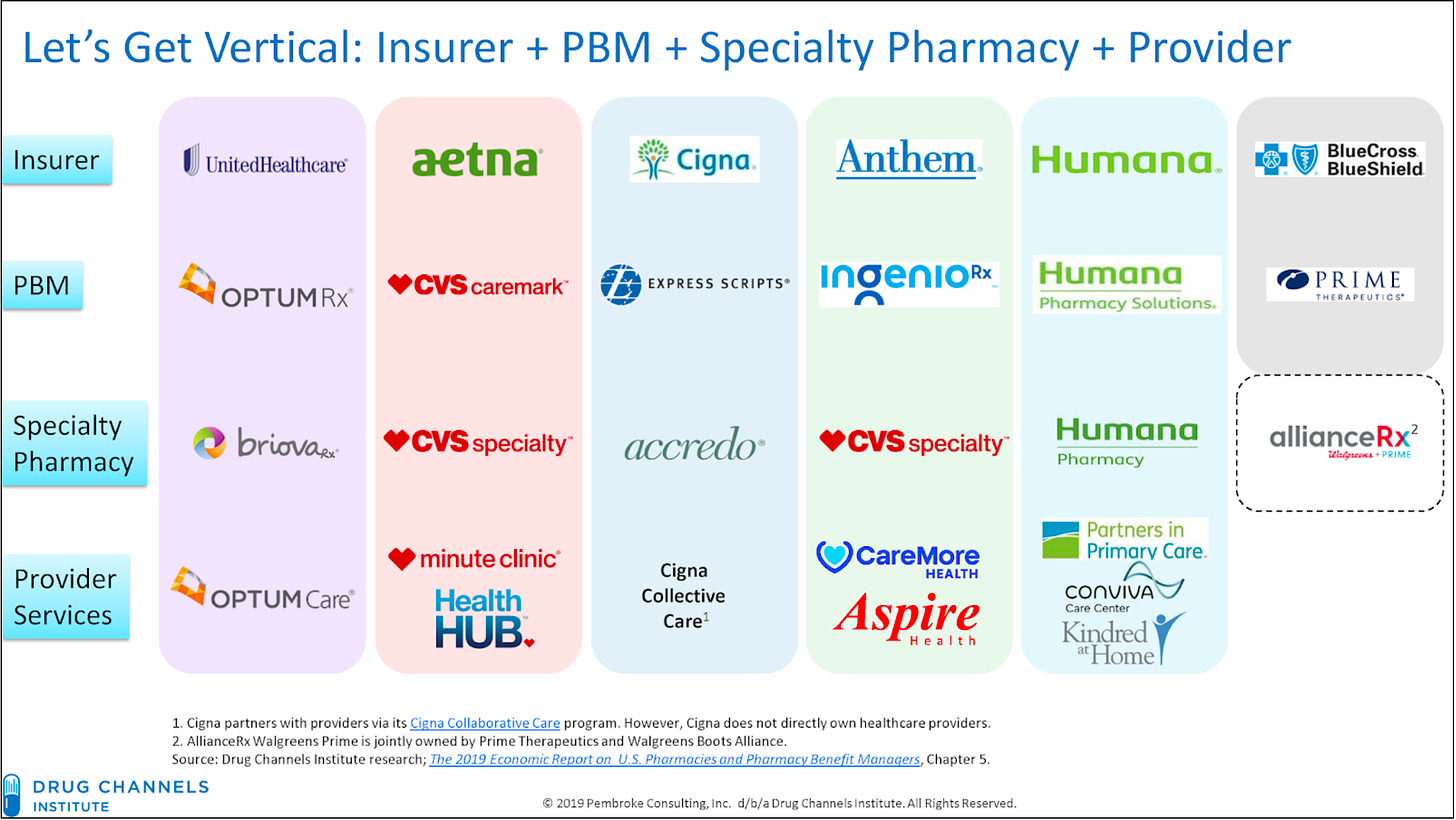

This is called vertical integration. It’s usually billed as a good thing for patients—all of your information in one quick stop!—but most evidence actually shows the opposite.

Instead, vertical integration typically means you’re siloed into one of just a few potential options. And because there’s almost no competition, each silo is pretty equally bad.

Source: https://www.drugchannels.net/2019/12/insurers-pbms-specialty-pharmacies.html

Making it even worse, each of these insurer/specialty pharmacy entities has the market power to control their patients’ pharmacy options through exclusive contracting. In other words, if you’re insured by Aetna, you can only use CVS Specialty Pharmacy. If you’re insured by Cigna, you’re looking at Accredo. These lessens even further each consumer’s options, and therefore, the competition between specialty pharmacies.

For example, because of employer changes and the CVS-Aetna merger of 2018, I’ve had to switch from CVS Specialty to Aetna's (pre-CVS acquisition) specialty pharmacy, then back to CVS Specialty. None of these transitions, requiring the transfer of data and a new prior authorization each time, was smooth.

The banality of evil

This is not always the case; there are a few niche specialty pharmacies that have contracts with certain drug manufacturers as the exclusive provider of certain drugs. That gives the niche specialty pharmacy the power to demand contracts with each insurer, to operate as an additional option (for certain drugs) alongside the insurer’s exclusive specialty pharmacy. It’s also possible for smaller pharmacies to theoretically develop relationships with certain providers and/or insurers and get access that way.

But my sense of the market is that such cases are rare.

340B Program

But specialty pharmacy is an even weirder world than these stats make it seem.

If you’re a health care person, you’ve probably heard of the 340B program, although you might not know what it does.

In short: ostensibly to help out poor and rural hospitals, the government offers a drug discount program called 340B. Under this regulation, drug manufacturers must provide outpatient drugs (not vaccines, and there are other carve-outs that I’m ignoring here) to certain covered entities, like safety net hospitals, at much lower rates than the hospitals would normally pay.

The rates are proprietary, but a MedPAC report from 2015 estimated that the rates are, on average, about 23% lower than a hospital would normally pay for the drug (other sources estimate a 30-50% discount).

Ostensibly, the 340B program is a good thing. It requires drug manufacturers to offer their drugs at a more accessible price for lower-income patients. But here’s where it gets tricky:

There’s no requirement for hospitals to pass on these savings to patients, so a hospital that gets a $4,000 cancer drug for $2,000 could still sell it to the patient (+ their insurer) for $4,000.

The language of the program is vague—so it’s unclear who qualifies as a “patient” under the 340B program, and many more hospitals than just safety net hospitals have found themselves eligible for the program.

Drug manufacturers have blamed losses from the 340B program as a reason for raising their prices.

How CVS further captures specialty pharmacy

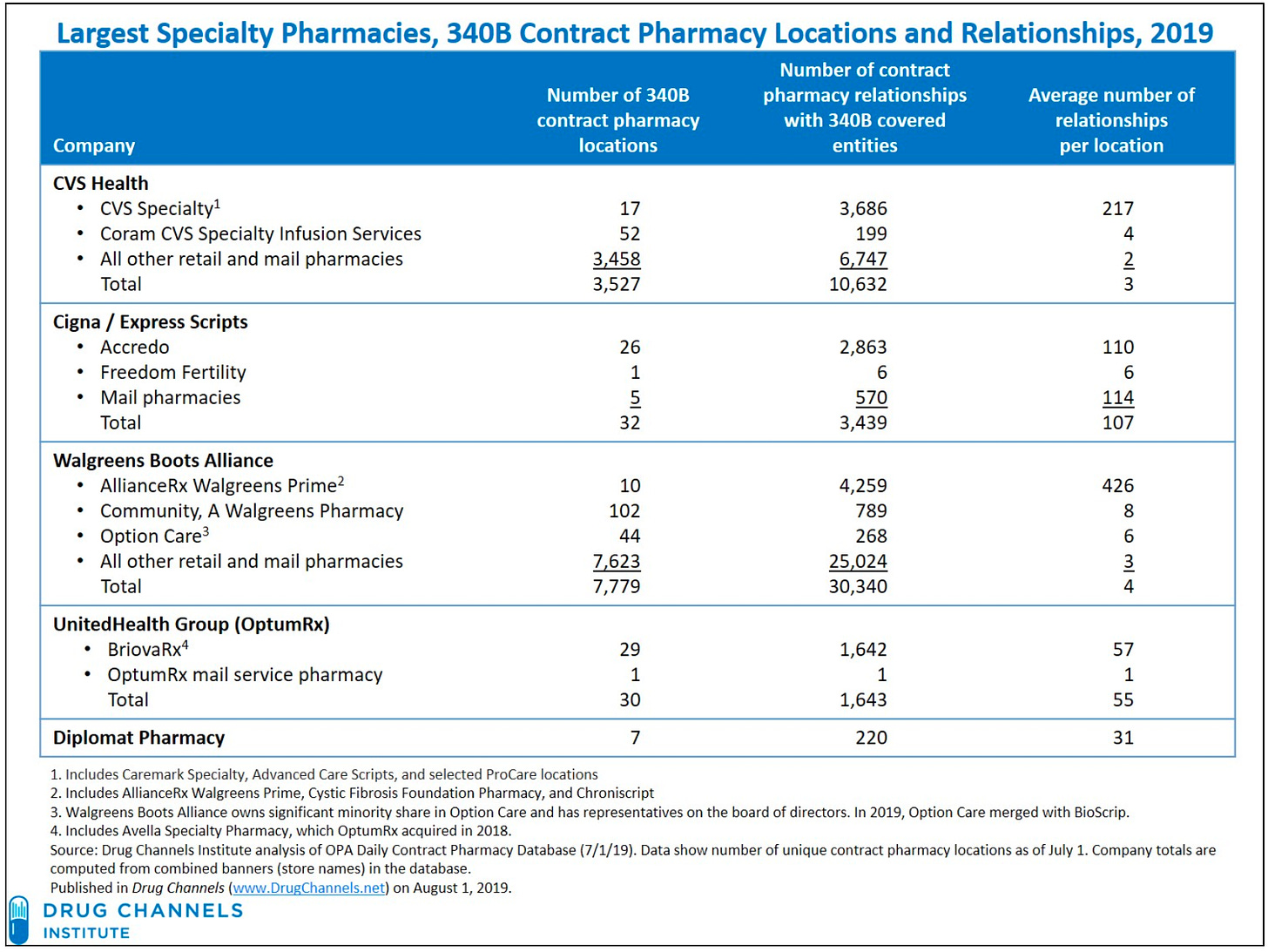

The biggest savings with 340B, because of the price differential, happen with specialty drugs. Many hospitals have responded by standing up their own specialty pharmacies—ostensibly a good thing, a source of competition for CVS Specialty and Optum.

But it turns out, to get their 340B savings, hospitals don’t have to own or manage the specialty pharmacy themselves. Instead, hospitals have turned to contract specialty pharmacies, meaning they contract out their specialty pharmacy business…to a huge entity. The biggest providers of contract specialty pharmacies are—you guessed it—CVS, Cigna, Walgreens, and OptumRx. Look at this chart, produced by, as with the other charts in this newsletter, Adam Fein and his Drug Channels site. 👇

Source: https://www.drugchannels.net/2020/04/the-top-15-specialty-pharmacies-of-2019.html

The result is that there are truly very few options for patients using a specialty pharmacy. Even if you get your specialty drugs through your local hospital, in all likelihood it’s passing through CVS or Walgreens, at a federal discount that you’re not seeing, which gives drug manufacturers the excuse they need to continually raise prices. Really a stunningly bad system. The only thing that would make this worse is adding middlemen. Oh wait, pharmacy benefit managers (which are also…owned by CVS, Cigna, and Optum).

Conclusion

There’s a lot here, obviously, and I didn’t even touch on all of it. For example: how did PillPack circumvent these huge players? (They weren’t a specialty pharmacy, but they did go up against CVS and SureScripts, et al.) How would you begin to try to compete?

I’m going to spend time the next few months talking to people in the specialty pharmacy space and trying to answer these questions. If you’re one of those people or you know one of those people, let me know! The system may not be primed for disruption, but it could certainly use it.

Of course, this would be a lot easier if regulators looked at the existing pharmaceutical industry for what it is—a corrupt system with very limited thought for patients.

Also: if you want more on corrupt pharmaceuticals, the Grassley-Wyden insulin report came out recently—I think they hold their punches but nonetheless, hidden in the bland language is some pretty stunning manufacturer/PBM interaction that adds up to exorbitant insulin prices. More on insulin to come.

Very informative. My fiance and I are both nurses, and we talk all the time about the time and energy that we waste while dealing with painfully inefficient specialty pharmacies.