The end of the independent doctor and the future of healthcare reform

The doctors become the working class

I’ve written quite a bit about consolidation of physician practices — by health systems, private equity, and payors — and how physicians are now, for the first time in American history, majority employed rather than independent.

To be clear: I think this is a bad thing. Independent physicians as a whole provide better care at lower cost, and the ability to choose where you practice allows more healthcare that’s purpose-fit to its location.

However, it is very difficult for physicians to remain independent, given trends in reimbursement, administrative burden, and consolidation across the system. And this is changing how physicians perceive health policy — which may, in turn, shape the health policy conversation in America.

Shifting politics

Physicians’ politics are shifting in general. Doctors are increasingly liberal (even though they’re less likely to vote than people in similar white collar professions). This isn’t entirely because of changing work dynamics; other reasons include education polarization and the increase of women entering the medical field. But…it’s at least partly because of changing work dynamics, per this quote from a 2019 Wall Street Journal piece:

“I don’t have the same interests as someone who’s in independent practice,” said Jane Zhu, a 34-year-old who is employed as an internal medicine physician at a large health system in Portland, Ore.

This is striking: the nature of this doctor’s work means that she perceives healthcare differently. To take this point one step further, physicians have gone from being “the man” to being the labor — and this is changing their policy positions as a whole. Some doctors are even considering organizing in unions.

A turn against noncompetes

Changing political attitudes as a result of changing employment structures for physicians was also on display in the last few years, as the FTC nearly banned noncompetes.

To editorialize a bit, noncompetes are almost universally bad. In recent years, restrictions originally intended to protect trade secrets and prevent high-level executives from rapid job switching have begun to be ever-more restrictive, expanding into construction and fast food jobs. Some employers make employees sign a noncompete even if enforcement of that clause is banned because it deters employee churn and entrepreneurship; the employee doesn’t want to risk breaking an unenforceable contract.

Former FTC chair Lina Khan proposed a national ban on noncompetes in 2023, and the depth of employee hatred for these restrictions was revealed: when the FTC submitted the proposed ban for public comment, the agency received over 26,000 comments, with more than 25,000 of those in support.

Then, this year, Trump administration’s FTC chair Andrew Ferguson essentially decided to let that ban drop. So now noncompetes are again permitted nationally, and the U.S. will revert to the patchwork of bans and allowances made by individual states. While some states have regulations carving out physicians from noncompetes, the national landscape is so difficult to navigate that the American Medical Association offers discounted contract review for member physicians.

Not all doctors are opposed to noncompetes; those who own a business tend to be more in favor of keeping this contract clause for their employees. One representative example is from this episode of the White Coat Investor podcast:

I think we ought to inject a little more nuance into the discussion… For example, our employees here at WCI sign a non-compete… We give them a list of the competitors and basically tell them they can’t start another business that’s essentially doing the same things as WCI. We view that as protecting some of the information about WCI, including how it runs and some of that proprietary kind of information. I understand why some businesses want non-competes, because I’ve got a non-compete.

This is a commonly cited concern by employers in the healthcare field (and those employers are increasingly health systems and private equity firms). For example, the American Hospital Association submitted a strongly worded letter to the FTC against the noncompete ban (which raises the question to me — how unhappy are hospital-employed physicians? The AHA seemed to be implying that they would leave and compete en masse).

An analysis of the comments submitted to the FTC published in Antitrust Magazine found that the overwhelming majority of comments were submitted by employed physicians. This wasn’t necessarily a surprise, as a poll by Medscape published in 2021 found that 90% of physician respondents reported being affected by a noncompete at the time of the survey or previously. Still, as Antitrust Magazine emphasized, “the vast majority of public comments were submitted by employees (not employers), particularly in the healthcare field.” That says something!

The future of health reform?

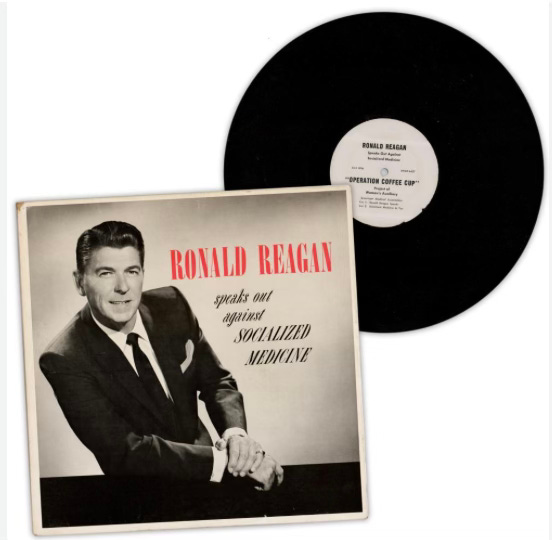

The changing priorities of its physician members has gradually shifted the American Medical Association’s priorities as well. For decades, the AMA has famously opposed any attempt at a national health plan, releasing in 1961 “Operation Coffee Cup,” which resulted in an LP of then-young actor Ronald Reagan speaking out against socialized medicine.

But more recently, the AMA has turned its attention to the issue of physician consolidation, monitoring instances of consolidation and encouraging members to share their experiences with mergers with the FTC.

In 2019, the AMA held a vote on whether to rescind its long-standing opposition to universal health insurance. Although the vote failed, it failed by just a few votes, with more than one publication reporting on the audible reaction in the room.

“I kid you not, there was an audible gasp in the room,” Sophia Spadafore, who at the time was a team leader in the medical-student section’s caucus, recalled. “All these delegates we had never met were coming up to us after, saying, ‘You’re doing it, you’ll get it next time, keep going, we support you.’ ” Much to their surprise, the students had come close to staging a revolution in American medicine.

Since then, the AMA has not had such a dramatic vote, and the official position of the organization is still opposition to single payor. But future health reform in America may not be just single payor (I don’t think it should be, personally) and policymakers may find physicians increasingly on their side.