The "hospital of the future" looks like a nightmare..

..unless policymakers and regulators step up

A quick note: My vision for this newsletter is a combination of more general, forward-looking posts (like this one), and pieces focused on a specific imbalance of power that has a negative impact on patients (like last week’s). To that end, the next few weeks will be a series covering private equity’s encroachment on various aspects of the health care industry. Stay tuned!

In March 2019, a year before COVID-19 struck, I found myself admitted overnight at GW Hospital in Washington, DC. My hospital bed was…in the hallway. They put up screens for privacy, but patients in wheelchairs accidentally knocked the screens aside. When the doctor finally got around to seeing me, he pushed the screens aside and said, “wow, beds in the hall? It’s like medical missions.”

As I learned from this doctor, GW Hospital was so crowded that day because another DC hospital, Providence, had just closed. It had been one of the only hospitals in Ward 5 (which happens to be where more of the Black population of the city lives).

The example of Providence—and of New York City this past March during COVID-19—directly refutes some health care observers’ opinion that hospitals are slowly going extinct. Instead, as I argue below, hospitals are slowly becoming the provenance of those with fewer options for care—usually those who already suffer disparities in disease and treatment—while richer populations with better access to networks both human and digital move toward more treatment at home. This difference in treatment location is likely to lead to more downstream problems as hospitals struggle to stay afloat with more patients less able to pay.

Source: https://doh.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/doh/page_content/attachments/2nd%20Draft%20CHNA%20(v4%202)%2006%2004%202013%20-%20Vol%201.pdf

The Providence closure saga began in September 2018, when Ascension, Providence’s parent company and the largest Catholic health system in the U.S., announced to Providence’s board its plan to shut down most of Providence’s services imminently. Providence’s board protested the decision vehemently. But most of them soon found themselves without jobs, as Ascension fired all but three and brought in a new, Ascension-approved board.

DC officials made motions to save Providence, but ultimately Ascension won.

Providence’s services were essential—now, residents from the Northeast quadrant have to shuttle across the city to GW or one of the other hospitals in Northwest. Majority Black neighborhoods on the East side of the city face a longer journey to receive emergency care, and the whole city suffers a dearth of hospital beds.

Enduring a lack of medical care is not new for residents on the East side of DC. Even before Providence closed, it and another hospital, United Medical Center, wound down their obstetrics services. These moves left the city without any labor and delivery care on the East side of the city at all.

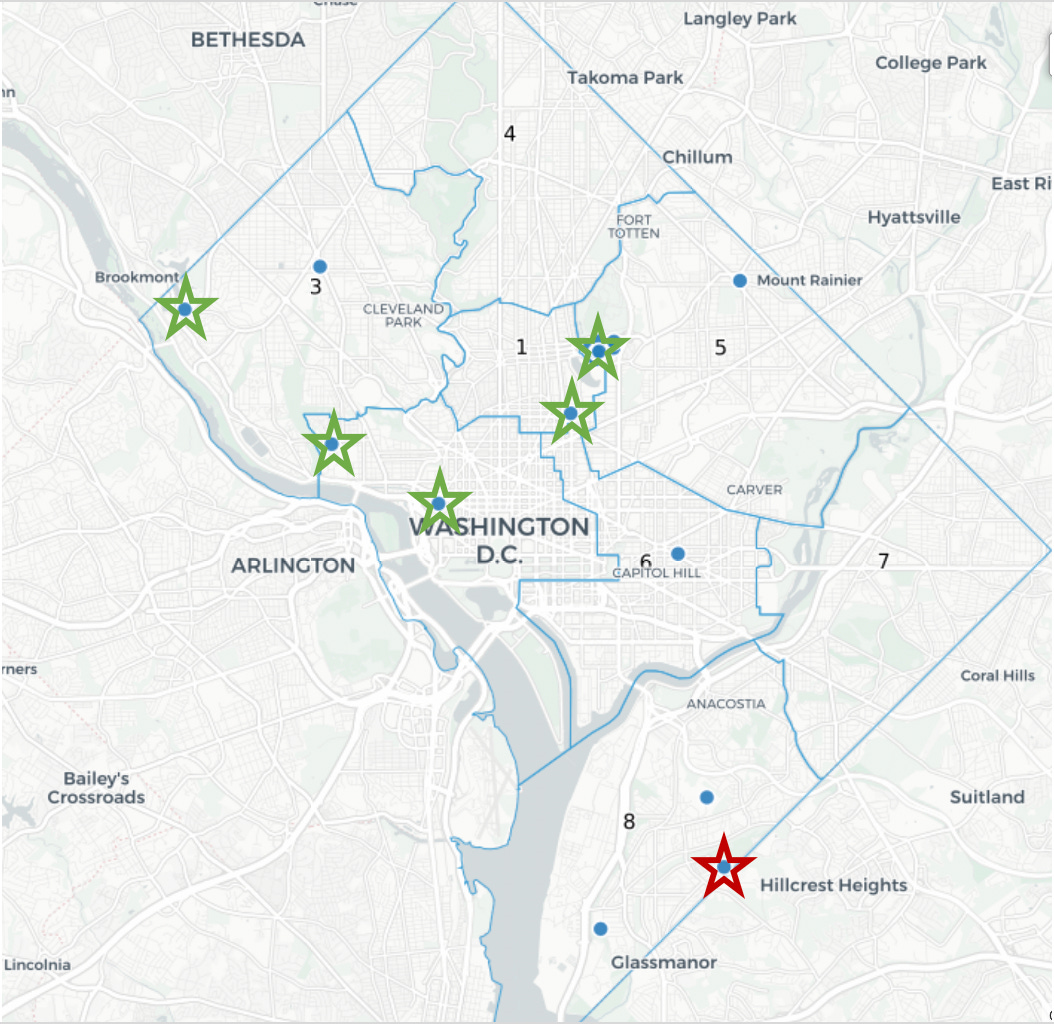

The green stars on the below map shows full-service acute care hospitals in the city. The red star denotes one of these hospitals, United Medical Center, which is slated to close entirely in 2023 after years of scandals around poor care.

The remaining blue circles denote facilities that are either psychiatric facilities, children’s facilities, or long-term acute care hospitals—certainly essential, but not the acute care services so desperately needed.

Source: https://www.wusa9.com/article/news/local/providence-hospital-closes-after-158-years-i-think-it-will-put-a-lot-of-people-in-jeopardy/65-9c9a17e2-92b5-4a35-bb23-bde122906ab7; with my edits

This March, New York City experienced an overflow problem on a much bigger scale.

As COVID-19 overwhelmed the city, hospitals were quickly stretched past their available capacity. The USNS Comfort, a Navy hospital ship, was deployed to the city’s harbor. Refrigerated trucks stood by to hold bodies that overflowed the morgues.

As I wrote in a report released by my organization, American Economic Liberties Project, NYC’s hospital system used to be much better prepared to handle surge events. But between 2002 and 2013, the city shuttered at least 22 hospitals with more than 6,000 beds between them. And a hospital closure that was postponed because its beds were needed for COVID-19 now appears to be back on—even though it’s a safety net hospital for residents of East Flatbush, Brooklyn.

Given these factors, keeping hospitals open might seem like an easy decision for state and local officials. But hospitals that provide the most essential care are often the most underfunded; if a community has a high rate of Medicaid patients or uninsured, the hospital may well provide crucial care with little reimbursement.

At the same time, health care thinkers are envisioning a future with hospital care at home. As health care goes increasingly digital, the argument goes, maintaining large, inefficient buildings full of excess capacity isn’t necessary. Officials should allow hospitals unable to stay afloat to close.

Hospitals of the future?

One example of this line of thought is an April 2020 post by Jorge Conde of venture capital firm Andreessen-Horowitz. Conde argued that “healthcare has left the building.” In an age of increasingly digital medicine, he wrote, a combination of predictive genomics, telemedicine, digital therapy, and ever-faster shipping, hospitals might become obsolete for all but the most complex cases.

For wealthier people, this appears to be true. New primary care subscription services like One Medical offer gold-standard care for people in major cities. Pricey health tracking data from Apple Watches and Oura Rings help their users gauge if anything is amiss. These wealthier classes have more access to wellness services and products like Equinox, Juice Press, turmeric shots…and basics as elemental as fresh produce.

Oftentimes, innovation that is first available to the wealthier and well-networked classes trickles across the divide to mass adoption (see the iPhone). But the divide in health care—in digital access, health literacy, access to care, social determinants of health—is more like a chasm.

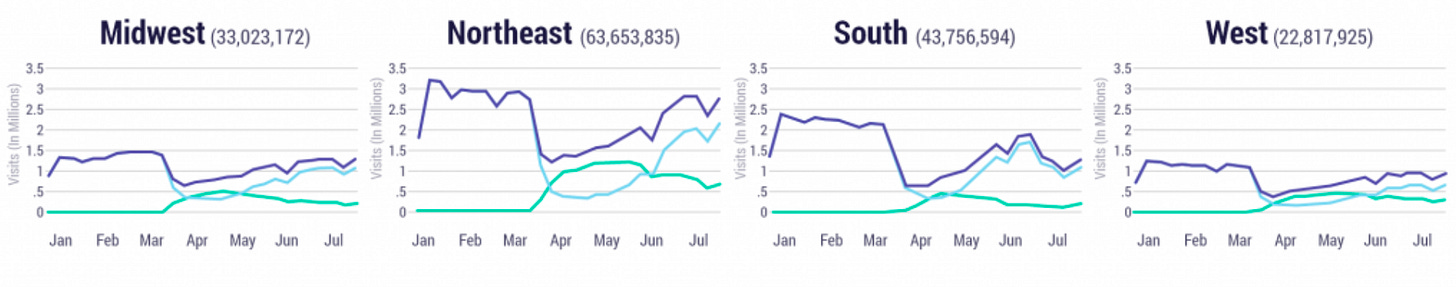

A more recent example of this complex chasm: telehealth during the pandemic. As communities across the country went into lockdown, in-person physician visits declined precipitously. In some areas, telehealth visits acted as a substitute for these in-person visits. But in other areas, people dropped out of medical care altogether. In the below graphs, the purple line represents total ambulatory physician visits, the light blue line represents in-person visits, and the teal line represents telehealth visits.

Source: https://www.ehrn.org/telehealth-fad-or-the-future/

As the graphs reflect, the telehealth bump was most pronounced in the Northeast region of the country. This may reflect the stricter lockdowns and heavier early toll of COVID-19 in that region, and it may reflect the generally wealthier and better-wired population’s ability to call into their doctor. The lowest bump was in the South, where lockdowns were less serious and patients, as a whole, have less access to broadband. The South had the largest drop in total visits—people simply didn’t see a doctor.

All of this is not to take Conde—and other people who believe hospitals are inefficient enough to warrant closure—in bad faith. I suspect he knows we still need emergency rooms and hospitals. But I think his thesis unintentionally reflects a structural problem in health care: wealthier, educated patients have a fundamentally different experience than poorer, less networked people. And by pushing health care to “unbundle,” we’re also pushing a disparate, delicate system to the edge.

Hospitals for poor people, digital solutions for rich people?

Two centuries ago, hospitals were treatment centers for those too poor or isolated to receive care at home. Without intervention, it looks like the hospital of the future will return to this, serving three purposes: First, to treat patients unable to receive home care. Second, as a treatment center for acute events like gunshot wounds that have a disproportionate burden on some groups but can affect anyone. Third, as standby capacity for black swan events like a pandemic or mass wildfires—which now, in September 2020, seem much more possible.

Maybe this dynamic could be okay, although it reflects deeper structural problems with American society. But hospitals in poor areas, as discussed above, have more difficulty making ends meet. Hospitals with less revenue are more fragile and more susceptible to being purchased by a larger health system or private equity group that rips out any profit (including, in at least one case, the real estate underneath the hospital) and leaves abandoned patients in its wake.

Conclusion

Again: this is not to say that digital solutions are bad. Instead, health care leaders in start-up world and the political space have to be more cognizant of these dynamics as they push for broad change. It’s conventional wisdom that poorer people seek care in the emergency room more frequently, that they’re a less profitable population, and that less profitable hospitals are more likely to shutter. But the real impacts on the community—namely, hospital closures that disproportionately affect Black and Hispanic people—are already here. And these dynamics will only be accelerated if and when wealthier people begin to pull out of the system to receive care at home. There is room for policymakers to both promote new innovation in health care AND help preserve hospitals for those who need them now and during black swan events.

In other words, we need to push leaders to pay attention to the changing dynamics in the health care space with a nuanced view: promote digital solutions AND fund community hospitals. Run pilot programs with novel start-ups AND block insurer megamergers (which harm start-up ability to break into the space anyway). This is a monetary and regulatory investment—but there’s really no other option. The “hospital of the future” is coming, but unless we want it to be both prohibitively expensive and geographically out-of-reach for large swaths of the country, it’s time to take action.