The next wave of the telehealth market is here

Next wave = it's fully a commodity

You know those health care topics that just feel too complicated to dive into, even as they’re becoming a bigger deal? That’s how I felt about telehealth.

I knew it was becoming a Thing. Obviously COVID-19 sped up adoption, and I kept seeing occasional mentions of a rumored acquisition. I had a vague idea that telehealth was becoming a commodity. But, as my manager at Advisory Board always used to say to me, what does that mean for the market? What does that mean for patients? I didn’t know.

But then Cigna announced an intent to acquire MDLive this week and I couldn’t put it off any longer.

First, I want to distinguish between telehealth and virtual care. I think the two terms are more or less interchangeable right now, although as the market matures, I’m sensing the definitions firming up. The following definitions are adapted from an a16z podcast episode and discussions with various health tech people (thank you all!):

Telehealth = synchronous or asynchronous care from PCPs or specialists, using video, phone, or messaging (example: Teladoc)

Virtual care = a broader care platform that encompasses telehealth, but generally has an integrated model that may be condition-focused (example: Thirty Madison), may have a specific theory of change (example: Parsley Health), or may integrate remote patient monitoring tools (example: Livongo)

The maturing market

Cigna’s acquisition of MDLive was just the latest in a series of actual and rumored acquisitions in the telehealth market. Most famously, Teladoc and Livongo merged in 2020, forming an entity that, at least on Twitter, became known as Teladongo.

The newly formed Teladongo unit is the subject of some excellent pieces and discussions talking through the value-add of the merger. The general consensus seems to be that:

Teladoc has a large pool of potential users, which it gained by pitching employers on telehealth usage and maintained by (generally) charging employers a per member per month fee, even if a member didn’t use the Teladoc platform.

Livongo has a large pool of mostly different users, who are more engaged than Teladoc’s members because Livongo offers a more engaging, long-term interaction for specific conditions (diabetes, high blood pressure).

By merging, the two can both overcome too-high valuations and cross-sell their services to new pools of users, while owning more of the telehealth market.

The very last point—that Teladongo has a chance to own more of the telehealth market—is, in my opinion, the most important. That’s because telehealth has become a commodity.

Telehealth is a commodity

I’m not the first to say that telehealth has become a commodity.

But if you’ve never heard that before, let me explain further. By commodity, I mean that telehealth is increasingly a plug-and-play, easy-to-layer-on-top-of-your-existing-offers kind of thing. This fundamentally changes the market strategy of telehealth companies. Rather than competing on the best offerings, the strategy for commodity providers becomes more about which entity can lock in the most market share.

Think of the general EHR market. Epic and Cerner aren’t that different. The game is less about new features and functionality, and more about locking in a limited pool of customers—in EHRs’ case, providers; in telehealth’s case, payers and employers. It’s not that new features don’t matter, it’s that long-term contracts and market share matter much, much more, because once most of the customers are locked in, they’re not really going anywhere.

And this is why it’s a big deal that Teladongo has more members than any single U.S. health care entity including UnitedHealth Group. It also explains why, as I describe further below, straightforward telehealth service providers are increasingly lumping together or with insurers as they try to eat up as much of the market as possible.

COVID-19 effects

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the commoditization of telehealth. Besides increasing adoption of telehealth broadly, the work-from-home environment demonstrated to many providers that it’s relatively easy to offer telehealth appointments. This is, counterintuitively, worse for telehealth service providers like Teladoc and MDLive, which is partially why they’re partnering up quickly.

On the provider adoption front, the hardest part, at least according to this Wall Street Journal interview with Mayo Clinic’s Chief Information Officer, was adapting the hospital’s workflow and…making sure employees had computers at home (i.e. eminently solvable problems).

And as Healthy Ventures laid out in a great Medium post last June, the pandemic-induced adoption of telehealth paradoxically hurts straightforward telehealth providers like Teladoc. As more physicians (like the Mayo Clinic, but also your local doctor) start to adopt telehealth, telehealth service providers like Teladoc lose a lot of their uniqueness. In other words, if you could just see your normal doctor via the doctor’s telehealth platform, why would you also seek out a new doctor on Teladoc’s platform?

Of course, as Healthy Ventures also notes, there may be some segmentation of the market here:

Now, a patient can stay with their regular doctor and system and get telemedicine treatment. Thus, for patients with regular doctors, we don’t expect them to go out-of-system to these telemedicine providers [like Teladoc].

Yet, for patients without regular doctors, or who are underinsured / uninsured, these telemedicine services are a good option, especially if their prices are transparent for cash-paying consumers.

But as Rock Health’s recent Digital Health Consumer Adoption Report points out (emphasis mine), COVID-19 mostly reinforced the adoption of telehealth among those already using the technology, rather than bringing new patient groups (which would be good for telehealth service providers) into the fold:

Telemedicine adoption (across all mediums—video, text, phone, etc.)…remained highest among subgroups which were (in prior years) already the likeliest adopters—middle-aged adults (35-54), higher-income earners, more highly educated, and those with chronic conditions.

Meanwhile, the 2020 data show comparatively lower adoption rates among groups historically less likely to adopt telemedicine: consumers from more rural areas, those 55 and older, and lower-income respondents. As such, the 2020 data suggest that the pandemic acted more to reinforce and accelerate underlying trends rather than to draw in new consumer subgroups as telemedicine users.

What this means for the market

Going back to my original question: what does this mean for the market? For patients and providers?

First, I suspect it means we’re about to see a lot of M&A activity in the telehealth space. The formation of Teladongo (and remember that Aetna is partnered with Teladoc for Aetna members’ telehealth services) triggered a rush by (mostly) payers as they seek to capture a corner of the commoditized telehealth market.

As mentioned above, Cigna recently announced its acquisition of MDLive. And Optum is rumored to be sniffing around American Well. Kevin O’Leary made a similar prediction when he wrote (emphasis mine): “I gotta imagine we’ll see American Well and / or Doctor on Demand gobbled up this year as well as folks get worried about being the last one without a dance partner in the telehealth space with the number of targets dwindling.”

And as telehealth enters the later stages of being commoditized and calcified within payer umbrellas, the market becomes much harder for new, innovative players to enter. For example, if Cigna/MDLive has 35% of employer contracts, Aetna/Teladongo has 30%, and UHG/AmWell has 35%, there’s very little room for new players to pick off market share (note also that I made those market share numbers up).

New players may have to end-run around the telehealth market by building a virtual care model, which is more complicated and may have a lower market ceiling than straightforward telehealth.

(Which, by the way, appears to be what Teladongo is trying to do.)

As for patients and providers, the most obvious outcome is that they have more access to telehealth, and that providers streamline their workflows to incorporate both telehealth and in-person visits.

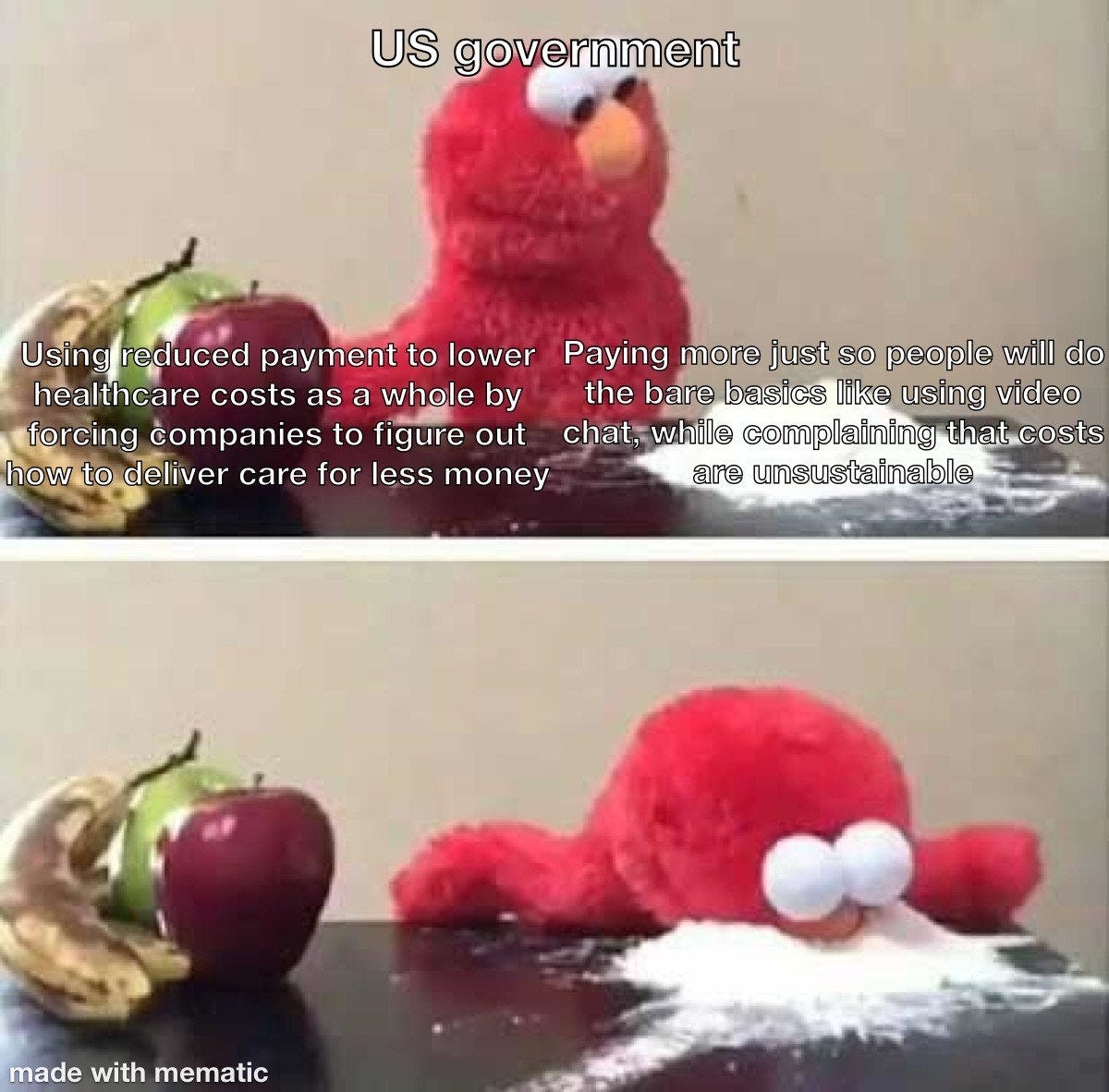

Nikhil Krishnan also made an interesting point, relevant for patients, in his take on the Teladongo merger: there was a world in which lower telehealth reimbursement drove down overall visit costs. But instead, by reimbursing telehealth visits at parity with in-person visits, we’ve essentially subsumed telehealth into the broader system without improving much of anything.

Conclusion

The next few months and years will be telling. What happens to the market after COVID-19? Does Optum acquire AmWell? Do Teladoc and Livongo integrate smoothly?

Depending on the answers to these questions, this post could be proved wrong. Nikhil noted, as did Sari Kaganoff of Rock Health, that telehealth providers and their insurer partners may seek to build in-person, physical spaces to capture the care that requires more than a video visit, differentiating beyond just commodity telehealth services provision. AmWell could stay independent. Employers could decide they don’t need to offer a specific telehealth service in their benefits package because every provider offers telehealth on their own. Each of these outcomes would change the calculus above.

And what of all the promising virtual care companies, like Virta, Oshi, and Thirty Madison? My guess is that they remain more nimble and innovative than the acquired telehealth services providers, and that they enter more interesting partnerships (like Oshi’s recently announced study partnership with a large, national payer).

Either way, the market is changing dramatically.

Great read! Was wondering what your thoughts were on the strategic rationale for payers in regards to potential M&A with telehealth providers like Teladongo/MDLive/Amwell? Would it be because payers building out their own telehealth platform would be too costly/take too much time? Or is it more of a play to have access to the millions of patients already 'aligned' with Teladongo?