The “on-ramp” to capitation

A moderately deep dive into Direct Contracting

I like to think of myself as someone who pays a lot of attention to healthcare trends. When it came to CMMI’s direct contracting model, though, that was absolutely not true.

Before I started research for this newsletter, all I knew was that value-based care models can be contentious, and that they almost always seem contentious for insider-baseball reasons that those of us on the outside couldn’t possibly hope to understand.

But I learned a lot more while doing research (although the opposing camps and their reasonings are only slightly more clear).

The gist is that value-based models on a national level (excepting the managed care revolution, which is just a weird historical moment that I haven’t quite figured out) really took off with the Affordable Care Act. Besides increasing Medicaid access and subjecting all of us to the phrase “death panels” in perpetuity, the ACA also launched the idea of Accountable Care Organizations, or ACOs.

ACOs, which can take the form of either a participating hospital or a participating network of providers’ offices, are a kind of shared savings program that allow for minimal amounts of upside and downside risk depending on the provider’s performance on certain quality metrics for their Medicare population. (There are several models of ACOs that I am flattening here—more detail can be found on the CMS website, if you really want it.)

ACOs were a huge idea, although one that fell slightly short of its promise. Someone else fact check me on this—but I believe it was one of the first instances of the U.S. federal government rewarding value-based care (as opposed to rewarding blindly for every procedure or test).

(A quick note—the original ACO model is targeted at traditional Medicare patients, although because Medicare innovation usually triggers follow-on from private payors, private payors are also increasingly interested in value-based models.)

The ACO model seems to have been especially fruitful for independent providers—who have more control over their workflows and theoretically should be able to better manage their patient populations—and provider-led hospitals.

But ACOs didn’t exactly turn the ship of American healthcare spending. Some ACOs fell short, and some did remarkably better than others. This somewhat mixed outcome generated a lot of questions about whether ACOs are worth the time and manpower.

Relatedly, I love this snipe at health policy people in a Health Affairs article:

Just as ACOs have grown in popularity, particularly among Medicare providers—124 new participants joined the programs for 2018, while the percentage of participants in risk-based models doubled from 9 percent to 18 percent—so has grown the popularity—among health economists and policy wonks—of debating the efficacy of this model designed to control costs and improve health outcomes.

And this is what brings us to direct contracting.

Direct Contracting (as clearly explained as possible)

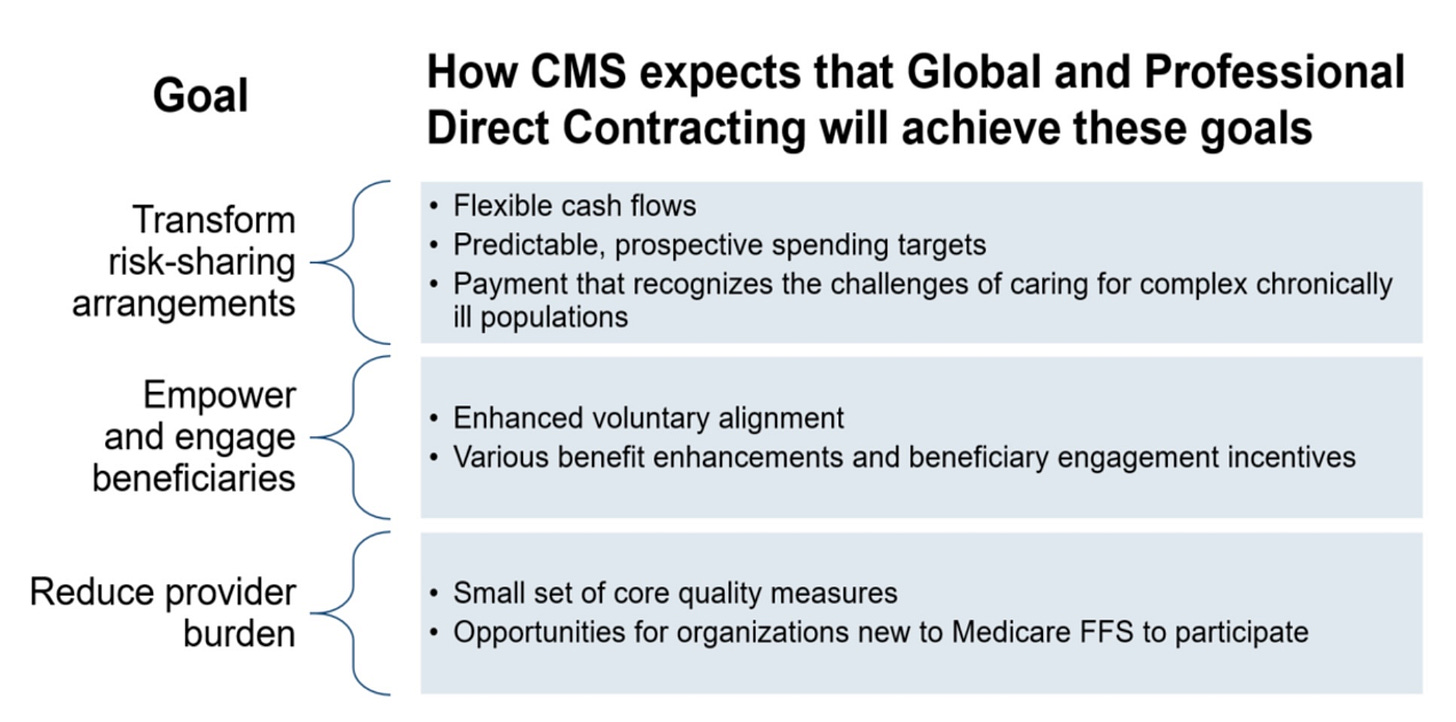

CMS, during the Trump administration, launched three new value-based models for providers to enroll in; all three models take value-based care a step further than ACOs.

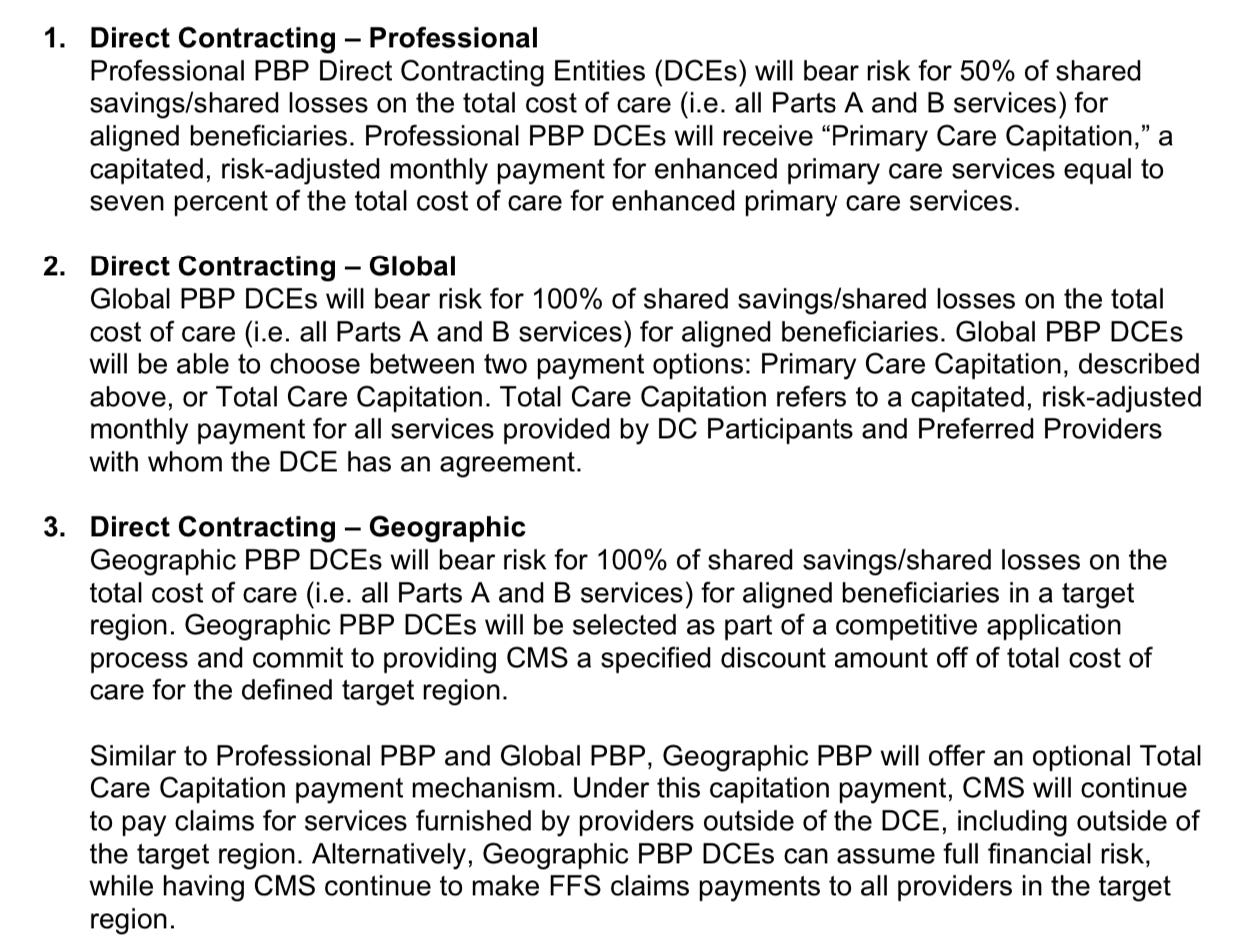

I tried to explain the three models myself, but they’re each complicated enough that I couldn’t do it without hopelessly plagiarizing. So here’s CMS’s description:

One complicating factor for the Geo Model not captured in these explanations is that DCEs, the network of participating providers, payors, etc., are responsible for all Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries in the designated region, not just those beneficiaries who see providers within the DCE’s direct network.

And one additional thing I want to really emphasize: the Professional and Global Model participants receive capitated payments—meaning a set amount per patient for, in the example of the primary care capitated payments, all enhanced primary care services. This is a huge step forward.

Not only is the risk level of these models higher than the risk level of ACOs, most ACOs do not receive capitated payments—instead, they share in the savings and losses of a patient’s expected costs in the fee-for-service system. In 2016, the Urban Institute referred to “shared risk [as] an ‘on-ramp’ to prepayment through capitation”—and now the Professional and Global Models are here.

(I’m trying to keep this readable, so I’m leaving out some details. You can see more about the Professional and Global Models here, and the Geo Model here.

If you’re familiar with ACOs and the amount of risk they incorporate, you can immediately see how this is a quantum leap forward.

Industry pushback

As far as healthcare controversies go, these new models sparked a big one. CMS is usually pretty deferential to provider and payor pushback, but the direct contracting model came out of nowhere with very fast launch dates, despite the pandemic. It was like CMS, all of a sudden, had decided that the U.S. was moving into a new age of value-based contracting, and there was nothing anyone could do to stop it.

Not that providers didn’t try. The National Association of ACOs (NAACOS) wrote to the Director of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) arguing that the Professional and Global models were targeted at provider networks that had never participated in an ACO, incentivizing them while making it more challenging for existing ACOs to participate in this heightened level of value-based contracting.

NAACOS also argued that providers might participate in these models to recruit traditional Medicare members over to Medicare Advantage, an argument echoed by the Center for Medicare Advocacy:

In many ways, the ‘Geo Model’ appears to turn more of the federal Medicare program over to private insurers – privatizing the Medicare program even beyond the growth in Medicare Advantage, (due in part to imbalanced payment, coverage and enrollment changes made in recent years). This new Model would actively target the still-majority of Medicare beneficiaries who choose not to enroll in private, managed care plans, and, in effect, force them to do so.

Reps. Katie Porter, Lloyd Doggett, Mark Pocan, and Bill Pascrell, Jr. had a similar argument in a letter to HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra this month, asking that he strongly consider pausing or permanently cancelling the Professional and Global Models, given that the demonstration has strong Medicare Advantage, private market overtones and could potentially diminish seniors’ choice.

Then, the trade group America’s Physician Groups shot out an opposing letter, calling one of the Representatives’ statistics a “red herring” and essentially saying they were factually inaccurate in their critique—that seniors will actually have MORE choice, and more access to add-ones (like meals as medicine) that will improve their care.

I don’t feel qualified to evaluate these claims (but they’re interesting in light of Clover Health’s recent turmoil over how many Medicare Advantage members they have).

In March of this year, CMS paused the Geo Model indefinitely, likely a combination of the new Biden team evaluating Trump-era policies and the pushback that the model received from trade groups. But the Professional and Global Models live on.

Conclusion

There’s...so much more to talk about here, I don’t know why it’s taken me so long to cover it. I’m particularly interested in how this has the potential to change primary care, and to potentially benefit buzzy primary care-focused startups like Iora Health and maybe One Medical. I’ll be researching this more—but if you have thoughts, please comment below or reply to this email, I’d love to hear.

This information shouldn’t be taken as investment advice (obviously), and the opinions expressed are entirely my own musings, not representative of my employer or anyone else.

Hi Olivia, thank you so much for writing this piece. I learned a ton about direct contracting!

One question I had was how it interfaces with MA plans and commercial insurers in general. It seems on first glance to be a relationship between CMS and provider groups, by passing commercial insurers. But then later on you say that many argue that the geographic model will end up in traditional Medicare members moving to Medicare Advantage. Can you provide more information on how exactly that would occur. Are MA plans entering into the Geo direct contracting agreements then? Or is it more that these provider groups would become like MA plans?

Another important distinction I think is that MA plans currently have a minimum MLR so they have a cap on how much of the medical savings they can retain (the remainder gets returned to CMS) Whereas I think with the geo capitation model, they would not be capped on how much of the savings they could keep, right?

I am also trying to wrap my head around the nuances of those in favor of and against direct contracting.

We spend more per capita and have worse health outcomes than any other OECD nation - clearly, our current model isn't working. And America seems to have accepted the need to shift away from FFS models and towards value-based care.

But then when the federal government seeks to incentivize capitation in a meaningful way - in doing so, extending primary care focused Medicare Advantage delivery models that have been proven to reduce unnecessary health spending and improve outcomes (Iora, ChenMed, Oak Street, Cano Health, etc.) - people get super worked up. At the same time, America seems to love capitation when it's a Kaiser or an Intermountain providing care (and receiving public dollars to provide care to Medicaid and Medicare eligible patients).

I've oversimplified a lot, I know. And I get that liberal politicians in particular might bristle at the specter of Trump-era policies that "increase privatization." But I do wonder what else I'm missing.