Value-based oncology and medication efficacy

What is "value"?

One of the most expensive conditions in American healthcare today is cancer. Cancer care costs are expected to grow to above $245 billion by 2030. At the same time, over the last few decades there have been real increases in the quality of life and survivability for people diagnosed with cancer, including a total 31% decrease in death rates from 1991 to 2018, thanks in part to advances in pharmaceutical treatments.

But, as many oncology researchers have noted, “cancer” is an umbrella term referring to hundreds of different diseases, with different locales, presentations, treatments, and prognoses. Treatment has not uniformly gotten better, and a cure-all—especially one that’s not painfully toxic to the body during treatment—remains out of reach, despite increased amounts of government coordination (and maybe more funding).

With the trend of American healthcare toward value-based care and the recent SPAC announcement of The Oncology Institute, a value-based oncology network, I started thinking about how value is determined for cancer care, especially when the drugs can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and patients’ lives can be at stake.

What is “high-value”?

In 2012, the American Society of Clinical Oncology released its Choosing Wisely framework, a list of 10 clinical guidelines on topics ranging from the use of antiemetic drugs to PET scans to multiple chemotherapy agents. This evidence-based framework, which was updated in 2021, gives physicians a nudge to avoid some of the most commonly unnecessary tests and treatments.

A study published in the ASCO journal in 2021, though, found that uptake of the guidelines by physicians has been limited, and that “further adoption of [Choosing Wisely recommendations] likely requires an implementation strategy that includes building stakeholder buy-in, and utilization of updated order sets and forced functions in technology to facilitate change.”

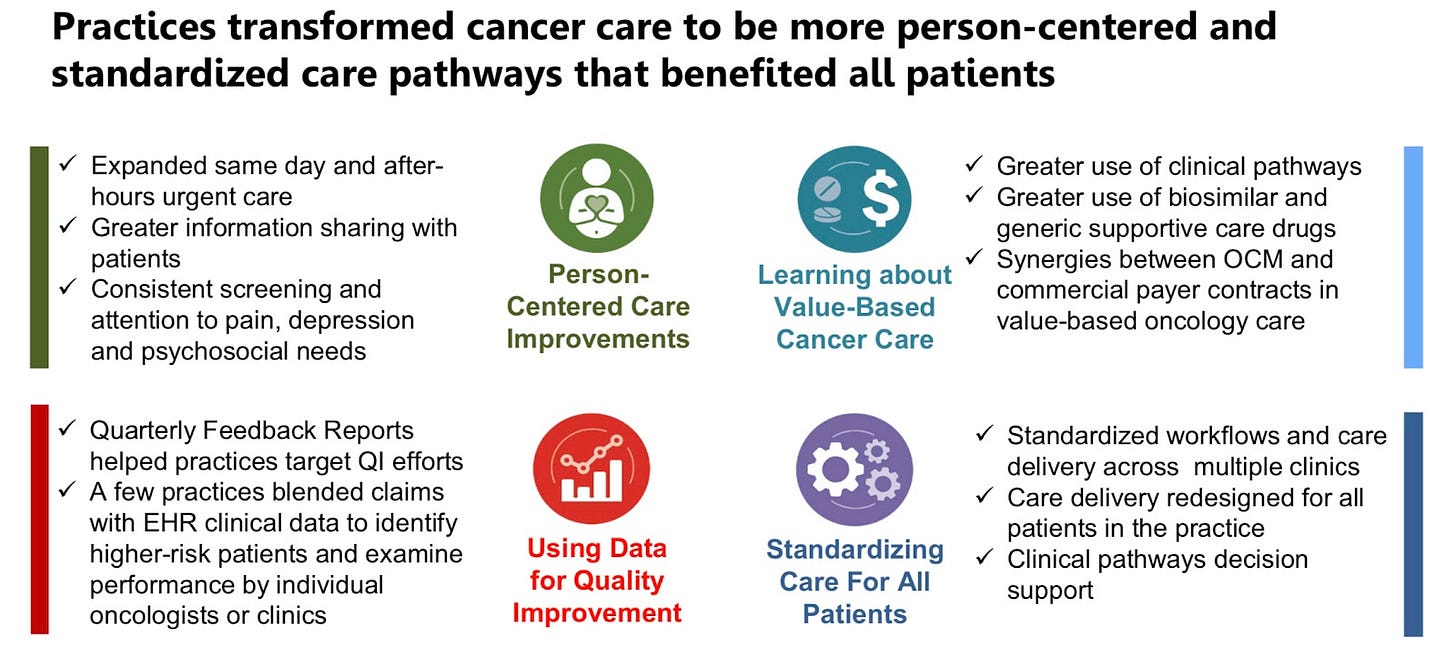

CMS, meanwhile, is also struggling with incentivizing lower-cost, higher-quality care. The Oncology Care Model (OCM) pilot, which runs from 2016 to 2022, encompasses 126 provider practices and 5 insurers. The OCM is specific to chemotherapy and offers two types of payment for practices: a per-beneficiary Monthly Enhanced Oncology Services (MEOS) payment of $160, and a performance-based payment for episodes of chemotherapy.

To date, the model has seen mixed success. OCM appears to have improved practices’ “high-value use” of supportive medications to treat chemo side effects, but the pilot overall lost money. The most recent reporting from CMS suggests that choosing value-based chemotherapy drugs remains very challenging, despite the incentive model.

Despite the nonexistent cost savings, though, patients seem to have received a better care experience.

In response to the outcomes of OCM, CMS is in the process of outlining a new model, Oncology Care First. OCF will likely offer incentives with greater sensitivity to cost (for example, adjusted payments for novel immunotherapies or metastatic disease), although the details are yet to be determined—and there is likely to be a gap between the conclusion of OCM and the beginning of OCF.

Tangentially, I’m interested in the implications of determining “value” in oncology by chemotherapy episode, rather than cancer episode. I’m far from an oncology expert, but my guess is that bounding care like this allows providers—and CMS, for that matter—to avoid asking unanswerable questions about how to handle value-based care for terminal patients. It’s also simpler, I’d guess, to gauge and control cost per chemo episode rather than per cancer episode. (At the same time, I do wonder if building in incentives for a comfortable, “good” death could improve how messy and drawn-out death can be in an American hospital—but that’s a different topic altogether. If you’ve never read it, Being Mortal by Atul Gawande is a classic.) — and if you have other thoughts or expertise on this, reply to this email and let me know.

Taking it as a given that we’re focused on chemotherapy episodes, then, the most obvious question seems to be—how do you determine value for chemo drugs?

High-cost drugs and personalized care

During a recent episode of the podcast Relentless Health Value, host Stacey Richter talked to Pramod John, CEO of VIVIO Health, which uses clinical evidence to build a formulary for self-insured employers. Dr. John noted that:

Clearly, as consumers, we all feel [that a low-efficacy drug would help us]. But what about physicians? Because ultimately these drugs are being prescribed, we can’t self prescribe. And in this case, as a physician, what’s your obligation when you [decide whether to prescribe a drug with a low efficacy rate]? …And then societally, what’s our obligation? Because all of us can agree that as individuals we should be able to buy whatever we like, but if society has to pay for us, then it raises an interesting question: what’s society’s obligation to pay for things that…harm more people than they benefit…How many people have to benefit before society is obligated?

As Dr. John notes, patients often think they will be among the small percentage that receives benefit from that drug. But given the expense of some drugs (and the challenges in determining efficacy, especially when drug trials are often non-representative of the population who would take the drug in the real world), the topic quickly becomes extremely complicated and emotional.

The way the medical industry handles prior authorizations also complicates matters. Prior authorizations are a blunt instrument that make more precision authorizations—which could, for example, be based on efficacy—much harder and more emotional. The current prior authorization system has created a paradigm where it’s standard for patients to have to beg for well-studied, mostly effective treatments for non-life threatening conditions—so a denial, even a denial for ultra-expensive, barely studied drugs, seems like something a patient has to fight, rather than a sound, personalized clinical judgment.

All of this brings us to what appears to be the key failure of value-based oncology to date: The medical system currently lacks the capacity for wide-scale, accurate determinations of a drug’s efficacy, especially on a personalized basis. Technology to gauge a drug’s effectiveness against a person’s genome is in its infancy, and clinical decision support exists but is rudimentary.

In short, although the technology exists in some form, we have a long way to go before we offer anything approximating true value-based care in oncology.

(There’s obviously a lot more to say on the technology component beyond what I’m covering here—let me know if you have thoughts, and stay tuned for a future newsletter on this.)

Conclusion

All of this being said, writing about this topic gave me hope this week. Many of the challenges the U.S. healthcare system faces are problems of intractable bureaucracy, fragmentation, and harmful consolidation. But the challenge of determining a high-value therapy for a cancer patient is mostly a question of science and computation. CMS’s pilot model was unsuccessful by its own metrics—but a big reason why it was unsuccessful appears to be that it’s still too challenging to precisely match a therapy to a patient. And that’s a problem that can be tackled with computing power, clinical trials, and basic research. So, while writing this newsletter this week had an aura of writing a newsletter at the end of the world, this thought gave me some optimism, and I hope it does you too.

This information shouldn’t be taken as investment advice (obviously), and the opinions expressed are entirely my own, not representative of my employer or anyone else.

It’s truly astonishing to see the scientific advances in cancer, especially in specific kinds of cancer. It’s even more astonishing that roughly 73% of persons diagnosed with cancer never get a second opinion and basically follow a care pathway dictated by the first oncologist they see and therefore don’t get the benefit of these advances. There are very clear ‘best practice’ or COE cancer protocols that include the use of genomic tests to recommend the most efficacious pathway (which often isn’t chemo) for the patient, yet patients continue to be subject to the protocols of the health system that they are driven into. While I entirely agree with your comments about our failures to assess drug efficacy up front (Pramod’s work is so important), I will tell you that many cancer COE centers are effectively using genomic diagnostic tools to assess tumors and also individualized drug efficacy and that many of these tools are quite advanced. I’ve had the benefit and opportunity to see the value of these personally.