Why don't Epic and Cerner go all-in on telehealth?

The short answer: Their clients don't really care about it. The long answer: It's complicated.

A few weeks ago, I was talking to someone from the U.K. when they asked a simple question: Why don’t Epic and Cerner have an integrated, widely used, HIPAA-compliant telehealth function embedded in their platform? Is there a chance that Epic and Cerner could ever compete with a company like Teladoc?

I immediately dismissed the idea but then started thinking: Why don’t Epic and Cerner develop a simple telehealth function?

(The answer: Have you met Epic and Cerner?)

How did we end up with Epic and Cerner?

In 2009, newly inaugurated President Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, a stimulus bill aimed at pulling the country out of the recession. A small subset of that act was the HITECH Act, or the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act.

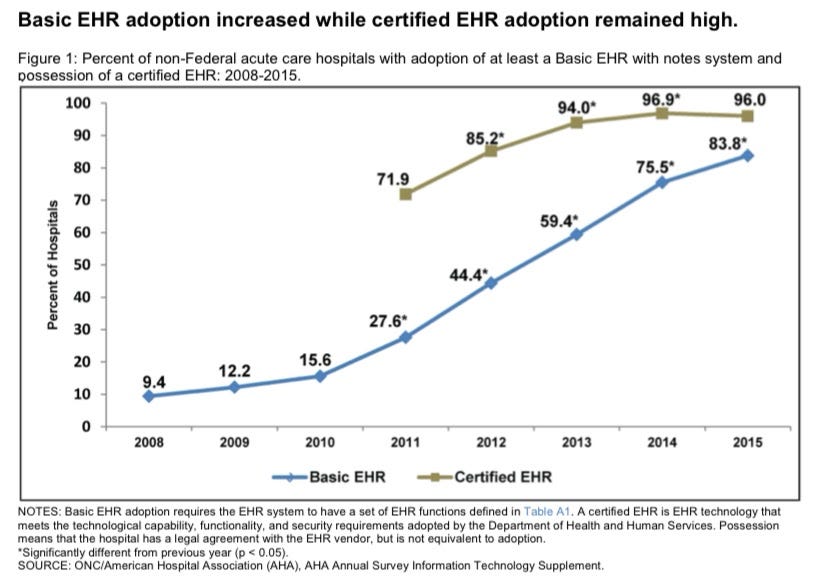

HITECH encouraged eligible hospitals to adopt electronic health record (EHR) systems. If these eligible entities met “meaningful use” benchmarks (for example, by 2012, capturing data, and by 2016, improving outcomes) using the EHR, the entities received incentive payments.

Before HITECH, providers knew they would have to adopt EHRs eventually—a 2017 Health Affairs article on the topic refers to hospitals’ “sense of inevitability” around adoption—but the incentive structure pushed many of the eligible hospitals over the line into adoption.

At the same time, the timing of the wave of adoption meant that, for hospitals, the game of musical chairs stopped primarily on two EHR options: Epic and Cerner.

Epic and Cerner were the best of terrible options in that they offered all the functionality hospitals needed, even while users found the software non-intuitive and clunky. But whether or not hospitals realized it, by choosing an EHR once, hospital leadership was essentially choosing an EHR for life. Epic and Cerner locked in long-term contracts that disincentivized switching. And with every additional month of training required to implement the software (and hospitals can spend months on training), the opportunity cost of switching became so great that many hospitals simply stuck with the software they originally chose.

Today, Epic is the largest, closely followed by Cerner. Although detailed data is hard to come by, especially for Epic, which is privately held, a 2019 report found that among 500+ bed hospitals, Epic holds a market share of 58%, and Cerner holds a market share of 27%. According to data that Epic showed to Forbes, Epic’s clients include nearly 2,400 hospitals worldwide and 225 million patients in the U.S.

It’s worth noting here that HITECH was focused on hospitals and that Epic and Cerner have primarily contracted with hospitals. Independent providers and provider groups have more options because they have more flexibility in their needs, and point solutions have popped up to serve those needs. That said, as more providers are acquired by health systems, more providers are having to use the EHR adopted by the acquiring hospital—and that’s usually Epic or Cerner.

Are these EHRs really so bad?

If you’ve ever worked at a hospital that experienced a go-live of one of these EHRs, you likely have visceral memories of the chaos it can cause.

It’s not all the software’s fault—many medical professionals were trained using paper records and may not understand all the available functionalities. And healthcare is complicated; it’s hard to fit all of the medical (and billing complexities) into a single software product.

But the software really is bad. Take one example, the clinical decision support that’s built into Epic (and probably Cerner too, but I’ve personally seen it in Epic). Theoretically, having pop-ups that notify doctors of potential drug interactions or allergies can be useful. In practice, Epic pop-ups happen so frequently that doctors have become totally inured to them. In one AMA review of the topic from 2015, the author cites research finding that physicians override more than 95% of drug interaction alerts and 49-96% of all alerts. Another study cited in the review found that PCPs spend an average of 49 minutes a day just processing alerts.

On the other hand, in a recent interview that’s really worth reading in full, Brendan Keeler of Zus Health told Nikhil Krishnan that Epic really isn’t as bad as it's made out to be, and that younger employees are even starting to like it. (I’ve had to use Epic and that sounds like Stockholm Syndrome to me, but offering it here as a counterpoint.)

Why don’t they have a telehealth option?

We’ve established that these EHRs are heavily integrated into the U.S. healthcare system in general and hospitals in particular. It’s software that physicians spend the bulk of their days using, it’s on every computer in the hospital, it seems like the obvious next step would be to add a telehealth option. So why haven’t they?

First, Epic and Cerner make the bulk of their money serving hospitals. And while there are increasingly outpatient, specialty providers tied to hospitals, especially in this era of provider consolidation, Epic and Cerner are selling to hospital leadership that are very focused on inpatient, in-person care provision. After all, Epic and Cerner’s sales pitch (besides being available around the time HITECH was implemented) is that they can handle the complexities of inpatient care. (Epic and Cerner have also expanded into other aspects of care that appeal to hospitals, particularly revenue cycle management, software services, and other data maintenance and provision.)

Second, Epic and Cerner are already locked in! They have long-term contracts; in fact, Epic brags about having never lost an inpatient hospital client except for acquisitions.

And also...Epic has one of the strangest cultures of any healthcare company in the country, one that’s not particularly conducive to market pressure or the wishes of the broader healthcare system.

Although Epic has been in existence for decades, it remains a private entity with a 47% stake owned by its idiosyncratic founder, Judy Faulkner.

Faulkner has refused most venture capital money and has only a few business partners. This means Epic has been largest insulated from external forces, allowed to grow and mature without too much outside input. The most obvious manifestation of this insularity is the campus, which is sincerely like a real-life Willy Wonka movie:

What does this mean?

When the pandemic hit and telehealth usage spiked, suddenly providers needed a way to provide telehealth.

And it took months for Epic and Cerner to catch up. In May 2020, Epic launched a partnership with Twilio to offer telehealth functionality. Then, in late 2020, Cerner launched a free telehealth option for rural hospitals. But for both, it was a second thought. Providers had already found other work-arounds.

Cerner recently hired Dr. David Feinberg, formerly of Geisinger Health and Google Health, as CEO. To me, that heralded a new era of Cerner seeking to be more proactive in tech innovation. But then this week Dr. Feinberg spoke at the Cerner Health Conference about the need to further integrate, further smooth out healthcare, the usual—with no mention of telehealth. Instead, he spoke about how the new era of value-based care calls for better revenue cycle management.

And I realized that the value add for Epic and Cerner was never—and probably never will be—making telehealth more accessible. Their clients aren’t patients or even providers, their clients are the senior management teams of hospitals—and those clients have no need for better telehealth access, even at the height of the pandemic.

Conclusion

I wanted this to be a piece about how Epic and Cerner are making the same mistakes that Kodak infamously made. That they’re ignoring technological change and missing the fact that telehealth is becoming an enormously important aspect of healthcare provision.

But then I realized that that conclusion, although buzzy, would be dishonest. The real answer is that Epic and Cerner have leveraged policy changes and the fundamentals of the market to dig a moat around hospitals so deep that they don’t have to pay attention to major changes on the outside. Epic and Cerner won’t try to compete with Teladoc because they don’t have to. Far from heralding their downfall, Epic and Cerner’s lack of attention to telehealth is a sign of their entrenchment and market power.

This information shouldn’t be taken as investment advice (obviously), and the opinions expressed are entirely my own, not representative of my employer or anyone else.