Will expensive cell and gene therapies force a different insurance structure?

Or we’ll all just suffer instead

Mark Cuban recently went on STAT News’s Readout Loud podcast and talked about how drug prices are so high that he ended up funding, out of pocket, $1.8 million to cover therapy for twins suffering from a genetic disease.

One of his ideas for how to make this therapy more affordable:

I have three kids and we got…the cord blood thing for all of them, where you save the cord blood and pay X amount a year, but there’s a 99% chance you’re never going to use it.

And so what I’ve suggested is that some of these million-dollar cell and gene therapies go to families through us or whoever and say, look, it’s a dollar a year per child. Or it’s a $50 or a $100 one time fee.

And you accumulate all of this and we’ll put it in escrow so you’re not just running out the door with it and this protects this family, any given family that participates, in the event that they have whatever disease that your therapy works for.

But a better analogy than cord blood banking is…….insurance.

(To be fair to Mark Cuban, if you actually listen to the whole episode, he has nuanced thoughts about how the entity that’s on the hook for payment, whether it’s an insurer or an employer, needs a system of reinsurance for these ultra high-cost drugs. The cord blood banking metaphor is more of a throwaway idea.)

All of this to say, the cost of cell and gene therapies is so high as to challenge the current insurance system altogether. And rather than inventing new types of insurance on top of the current system of insurance, it seems like a good point to pull up and reevaluate everything.

The high-cost therapeutics era

In June of this year, I wrote an update to another article I had written in 2020, about caring for (and trying to reduce the cost of) the most expensive patients. But if 2010s were focused on value-based care, the 2020s vibes are turning toward high cost, fix-all therapeutics. And that completely changes the calculus of reducing the cost for patients.

Even several years after GLP-1s exploded onto the scene, they still seem to be a miracle drug, capable of improving obesity, cardiovascular disease, addiction, and Alzheimer’s. At the same time, cancer therapeutics are making leaps and bounds even as they get more expensive, expanding into CAR T therapy and more. If the current pace of drug innovation keeps up (by no means guaranteed), we might all be on a high cost therapeutic someday.

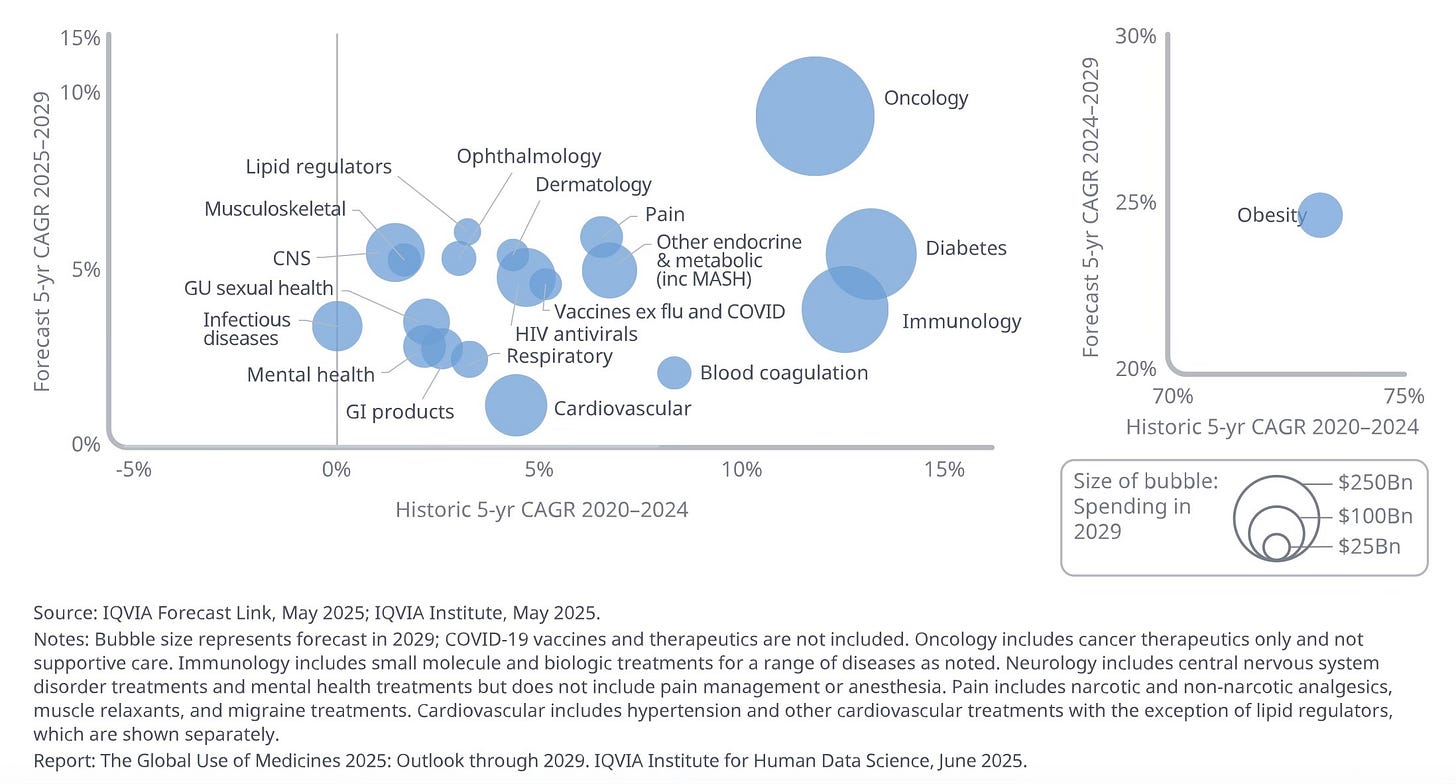

This chart from IQVIA maps global spending on drugs forecast for 2025-2029 compared to historic data from 2020-2024 (it’s a confusing chart, I’m sorry, I didn’t design it). They expect oncology drug spending to continue to rise at a fast pace, diabetes and immunology drug spending to slow, and obesity spending to slow but still be high enough as to require an entirely separate part of the chart.

And in that case, all the efforts of 2010s-era value-based care might not mean very much.

Obviously prevention and early screening is far cheaper and has fewer side effects. But if a drug takes up far less of a doctor’s time and is more likely to actually work than intensive counseling, the incentive structure is stacked toward just prescribing these drugs for everyone.

And if that’s the case, doesn’t that reshape how insurance works? If the major cost becomes not procedures but therapeutics, then insurance must prepare to bear the burden of lifelong therapy or a one-time fee that’s very high compared to a standard procedure cost. And if that’s the case (a few assumptions are obviously embedded here), insurance is likely to become even more prohibitively expensive.

Reinventing insurance from first principles

So then what’s the answer?

Option 1: As many of these drugs were developed, at least in part, with federal research dollars, the government could declare that lifesaving drugs are priced too high and have to come down. I know I sound too glib for industry people on this, but this is a viable option. Yes, the R&D costs for drugs are high, and we want to incentivize drug companies to continue to take risky bets on developing blockbuster drug rather than less risky follow-on drugs. At the same time, do we want a society where that means blockbuster profits at the expense of patients in perpetuity? The government grants research dollars (although notably less under RFK Jr’s HHS) and confers temporary monopoly status through the patent process. I think it’s fair for us to ask for a little more in return.

Option 2: Insurance structures (and PBMs) have to change. The way the system currently works, manufacturers develop the drugs, and PBMs decide on behalf of payors what will be included on their formulary, or the list of covered drugs. Many patients who rely on expensive drugs lose access when the PBM decides to change which drugs are on a certain formulary or exclude other drugs. As the New York Times reported in 2023:

Scott Matsuda was hit with the formulary problem when his doctor prescribed him a new drug to treat myelofibrosis, a rare type of chronic leukemia. For years, before the drug was developed, his insurance paid for a cocktail of chemotherapy drugs that did little to slow the course of his disease and caused difficult side effects like severe mouth sores.

Then, he entered a clinical trial of Jakafi, a pill that markedly slowed his disease. He did not notice any side effects.

“It was amazing,” Mr. Matsuda said. “I was really happy.”

Three months later, the trial ended, and the F.D.A. approved Jakafi. The daily pills that were saving his life cost $6,000 a month, but Jakafi was not on his insurer’s formulary.

“We were dumbfounded,” Mr. Matsuda said. He and his wife, Jennifer, have a photography business near Seattle, but that price was totally beyond them.

“We are solidly middle-class,” Mr. Matsuda said. “We pay all our bills. We have a good credit score. Six thousand a month would ruin us.”

If the formulary becomes less exclusive, the PBM loses some of its negotiating power and a lot of its rebates (manufacturers pay rebates to PBMs to maintain formulary position, a practice that the FTC called out in 2022 as being rife with the possibility for illegal bribery). For insurers to be on board, they might also require some sort of reinsurance program as Mark Cuban proposed, which would provide insurance for the insurance companies. Such plans exist, but this article published in Milbank Quarterly earlier this year notes that some reinsurance companies, not being subject to the same Affordable Care Act rules that health insurers are, exclude cell and gene therapies from coverage altogether.

Option 3: We reinvent insurance from first principles and all pay into a system that probably increases its premiums pretty dramatically every year to account for the wider breadth of therapies available for different conditions. This system would probably invent prior authorizations from first principles too, because many of these therapies for genetic conditions have to be given when a child is very young and won’t have paid much into the system yet.

Option 4: We rely on GoFundMe and people fall through the cracks and die of preventable causes.

This new era of therapeutics challenges a lot of long-held assumptions about healthcare (although the magnitude to which this will actually change things remains to be seen): that prevention is worth spending more time and money on than treatment, that the insurance system is even capable of incentivizing meaningful prevention through value-based care, that the insurance system works at all.

If I’m being optimistic, maybe this is finally what forces some kind of health reform. Really, it probably just increases our premiums for now.

This is literally the topic of my TEDx earlier this year. We need business model changes/innovation in the business of health to match the speed at which invention and the tech stack is taking off. Otherwise cures and the like just sit on the shelf.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NbkW91PMGxg&t

Drug companies are also using copay assistance for higher priced immunotherapy biologics that require infusion. Not millions but thousands of dollars of treatment a year. Infusion centers and biological are growing >10% a year. The copay assistance from the pharma company helps the patient pay the copay so the insurance pays for the continued payment from the insurance company. Of course the PBM is in the middle trying maximize payment to them. A wacky system.