A better specialty pharmacy startup is just a lot of funding + some key relationships away

And, you know, contending with UnitedHealth

This post is something I’ve been thinking about for a long time.

It started with a question: why isn’t there a patient-focused specialty pharmacy? You could even bound it by condition. Imagine, for example, a Crohn’s disease specialty pharmacy. It would have pharmacists trained in the latest IBD treatment and advice. It would have people who picked up the phones quickly. It would have a team of patient specialists who were ready to give advice about how to make injections hurt less, or to help shepherd a patient through the prior authorization process. It would never lose your patient rebate card number (which is, in my experience, a lot to ask).

But this doesn’t really exist. This, in short, is why:

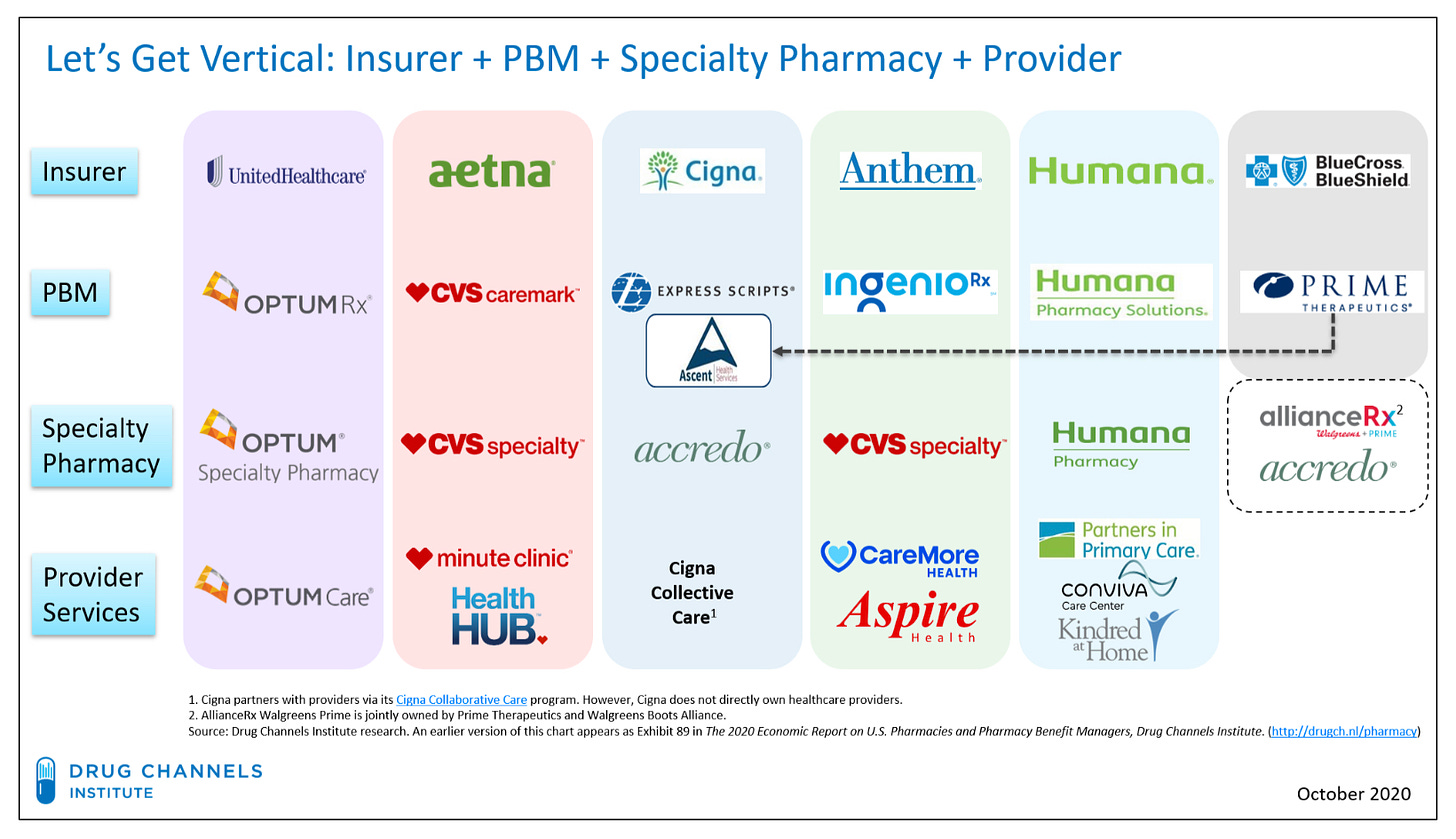

The U.S. has about 4 main insurers. All of them have their own specialty pharmacies. Aetna, for example, is owned by CVS, which has CVS Caremark, the specialty pharmacy, attached.

Because specialty drugs are so expensive, virtually no patients can afford to go around the specialty pharmacy system. For that matter, because each major insurer more or less requires patients to use their in-house specialty pharmacy, there really isn’t a way to go around, unless you’re negotiating with AbbVie yourself and paying hundreds of thousands of dollars a year fully out of pocket.

This means that the decisionmaker isn’t the patient, it’s the insurer. And as previously stated, all of them have their own specialty pharmacies.

So to start a new specialty pharmacy, you have to run uphill and get in-network with the existing insurers. Which means you need to find a co-founder or an otherwise very early hire with personal relationships at at least one of these major insurers, preferably more than one.

Even then, the experience you offer has to be so much better and so much cheaper that major insurers are willing to cannibalize their own specialty pharmacy business to bring you on.

I go more in-depth below.

What is a specialty pharmacy?

The definition is fungible, but there are a few major characteristics. A specialty pharmacy offers more expensive, more complex medications than a typical retail pharmacy. Instead of capsules or pills, specialty medications may be biologically or otherwise technically complex bioengineered drugs to treat conditions like cancer, autoimmune diseases, and hepatitis.

To dispense drugs like this, specialty pharmacies have to be accredited from one of three U.S. firms. You can see here some of the requirements by which URAC, one of those firms, determines accreditation:

Specialty pharmacies make money as a percentage of each drug. While the margins are lower than for traditional pharmacy, the gross prices are much higher. As Jake Galdo, a clinical assistant professor at Samford University in Alabama, told Elements magazine:

With specialty pharmacy, your margin is only 5 percent, but if the cost of the medication is $10,000, your 5 percent margin is $500. That covers the cost of dispensing, and then a whole lot.

This is becoming an even better value proposition as time goes on. As new biologics and related drugs come on the market, healthcare spending is increasingly shifting towards specialty drugs. In 2020, for the first time, spending on specialty drugs outpaced that of traditional drugs.

The status quo

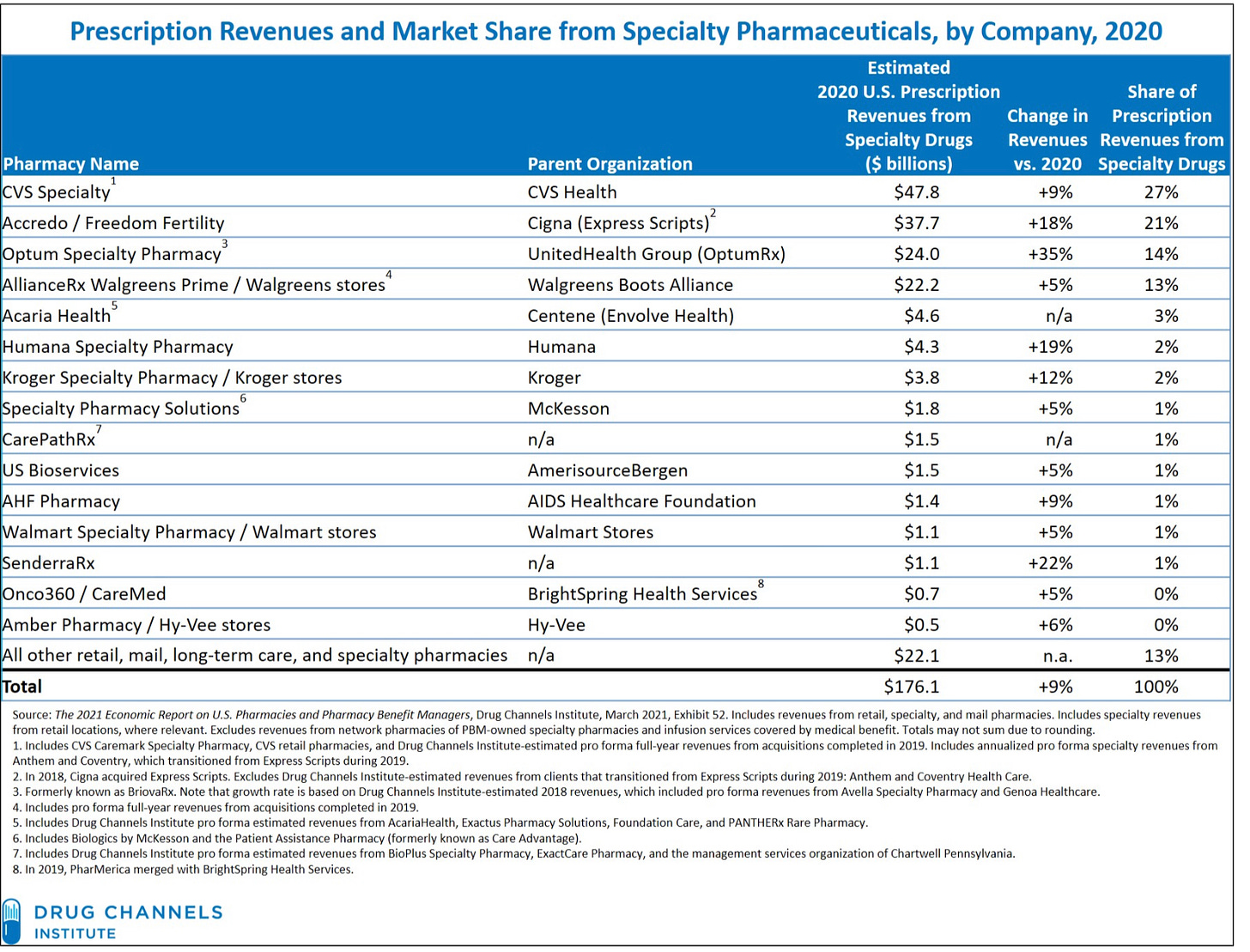

Although the specialty pharmacy market appears dynamic, with the number of specialty pharmacies growing rapidly in recent years, the market is unquestionably dominated by just a few vertically integrated corporations.

A large portion of the recently accredited specialty pharmacies are health systems accrediting their in-house pharmacies. As I covered in a previous post, this growth is largely artificial. Many health systems simply contract out for a specialty pharmacy rather than building their own, allowing the health system to take advantage of the 340B program without too much legwork. The biggest providers of contract specialty pharmacies are...CVS, Cigna, Walgreens, and OptumRx. In other words, the growing number of specialty pharmacies is more or less increasing the existing market share of the biggest players.

I’ve used the below image in a post before, but I’m breaking it out again because it’s a remarkable visual for the state of specialty pharmacy in the U.S. It’s also helpful in understanding why it’s so hard to access specialty pharmacy outside one of these big providers—and all the more so if you’re one of the approximately 44% of Americans on UHC, Aetna, Cigna, Anthem, or Humana.

The result is that, despite the ostensible proliferation of hospital-based (contract) specialty pharmacy, 75% of pharmacy-dispensed specialty drug revenue in the U.S. accrues to just the top four specialty pharmacies.

Unless something changes, this dominance is likely to continue—the top players aren’t sitting there passively.

Adam Fein at Drug Channels has suggested that Express Scripts is building out secretive, white-label products to attract more, smaller PBMs to get in on specialty pharmacy through the Express Scripts gate.

Meanwhile, large PBMs have started to increase their Direct and Indirect Remuneration (DIR) fees, which hit independent specialty pharmacies particularly hard. These fees are post-point of sale and are commonly either a clawback if the pharmacy receives a manufacturer discount, or a “pay to play” fee that the PBM charges the specialty pharmacy to retain its preferred status with the PBM.

The fees are so bad that Elements magazine blamed opaque and variable DIR payments as a major cause of the lack of new independent specialty pharmacies. Sheila M. Arquette, the president and CEO of the National Association of Specialty Pharmacy, told the magazine:

We currently don’t have performance metrics that are used to calculate pharmacy DIR fees based on this pharmacy type and the drugs dispensed and disease states managed, so it’s even more egregious because specialty pharmacies don’t have the ability to influence those metrics and mitigate the fees.

Is anyone trying to change the status quo?

Not publicly, at-scale. But I suspect (hope?) that’s not true for long.

Truepill, which offers a B2B pharmacy model for primarily DTC prescription companies, has hinted at moving deeper into specialty pharmacy. Truepill is a URAC accredited specialty pharmacy—but it’s not immediately apparent how or if they’re yet offering specialty pharmacy services alongside their B2B mail order pharmacy services.

I also wouldn’t be surprised if companies that offer more complex virtual care start to build out their own specialty pharmacies. I would love to see companies like Oshi, which treats IBS and IBD, add a specialty pharmacy layer to their services.

But while the margins are high, particularly for chronic care patients who will need specialty drugs for years of their life, the battle remains uphill.

For a company like Oshi to start offering specialty pharmacy, it has to either build a partnership with an existing specialty pharmacy, or build and accredit its own. Assuming it takes the build route, the company is now stuck with one of two challenging options. Either it offers cash-pay specialty pharmacy to its patients, perhaps layering on hefty rebates but still unavoidably charging tens of thousands of dollars—or it tries to sell its whole model to insurers. And the second option is challenging not only because insurers are notoriously slow to accept new models—but also because, by accepting an integrated specialty pharmacy, insurers would be cannibalizing their own specialty pharmacy business.

Conclusion

There is an upside for insurers. A smooth chronic care experience with specialty pharmacy layered on top is a huge leap forward for patients, and I suspect that both customer satisfaction and care (and therefore cost) would improve dramatically.

The biggest upside, finally, is for chronic condition patients, who would have access to a patient-centric experience where none previously existed.

This is why everyone I’ve talked to so far has strongly emphasized that, to build this model, a startup has to bring on someone with extensive insurer relationships—because building a good model is only the first part of the game.

-

Do you have thoughts or insight? As always, let me know by leaving a comment or replying to this email!

Also, thank you all for the support while I dealt with my insurance company! They overrode their initial decision and approved coverage of my Humira. Was it the angsty 11pm email I wrote them almost threatening to be more expensive if they denied the drug? Guess we’ll never know.

This information shouldn’t be taken as investment advice (obviously), and the opinions expressed are entirely my own, not representative of my employer or anyone else.

Nice article....Thanks for the perspective. FYI we have a child with CF and have had wonderful experience with a specialty pharmacy group called Modern Health, recently acquired by Kroger. They are extremely patient-focused and offer many of the "wish list" items listed in your first paragraph. They have maintained their high touch service through acquisition, which is even more impressive! The big bummer however is that my employer just switched to UnitedHealth on July 1, so now MH is out of network. I'm hopeful but but not bullish on OptumRX offering the same level of care for my family...