A new way to cash-pay

How Sidecar is circumventing the traditional health insurance process in an innovative way—and why it probably won’t be a venture home run

This topic is a combination of suggestions I got—thank you! I love hearing from people who read my newsletters and have thoughts, so as always, reply to this email or leave a comment if you have something to add!

There are several young insurance startups, each with a slightly different business model. Most, however, are hinged on leveraging technology to drive a higher-quality, consumer-friendly Medicare Advantage option, taking advantage of the money that’s available in serving an MA audience. But there’s one insurance startup, Sidecar Health, founded in 2018, that takes a totally different approach for its core business: Cash pay.

A Medicare Advantage strategy

In 2019, Abhas Gupta, a former VC and current CEO, wrote a great article categorizing Bright, Clover, Devoted, and Oscar’s Medicare Advantage strategies. It’s a little outdated—Oscar has gotten much bigger and is striving to be more nationally cohesive, and Clover’s stock has been in a “funk” (I think justifiably)—but the categories are interesting.

Gupta identifies three categories based on the company's delivery-side strategy. Bright Health and Oscar NYC, he says, use a strategy of partnering with health systems and letting them figure out how to make money with treating Medicare Advantage patients. Clover has the strategy of deploying provider representatives to supplement participating clinicians. And Devoted Health partners with sophisticated medical groups who, as Gupta says, “get it” and are able to drive cost savings.

Gupta writes that he has a “grim view on the unit economics of all these companies;” that while they may still have billion dollar exits (which Clover, Bright, and Oscar have since achieved, while Devoted Health recently raised a Series D with an $11 billion valuation), these companies ultimately “just won’t be venture home runs.”

Depending on how you categorize “venture home run,” it looks like Gupta might be right. All of these companies have done very well for themselves and their shareholders—but they aren’t changing the healthcare game.

Granted, each of these companies took on perhaps the healthcare market most hostile to newcomers. Health insurance is dominated by huge insurers with huge markets. To successfully sell to employers, the largest private insurance market segment, new companies not only have to offer more than the biggest players, they also have to convince insurance brokers, the go-between for employers and insurers, to start selling their offering as an option.

This is easier said than done—many brokers get perks and commissions from the major insurers to offer their product. And it can be equally challenging to go around the brokers; many have long term relationships with the C-suite at the companies they serve.

In short, health insurance is a hard market to be in. UnitedHealth might not be as technologically enabled as the newest health insurers—but it doesn’t matter, because UHG has 70 million beneficiaries, 75% more than the next largest insurer. I’m quite convinced that UnitedHealth is un-disruptable, except by, maybe, the Department of Justice.

Given all of this, Sidecar Health has a very interesting approach. Sidecar uses a business model that implicitly assumes it can’t disrupt the major insurers and that, instead, it can work around them.

Price negotiations

Sidecar is premised on the fact that prices for cash-pay patients are often cheaper than prices for patients with insurance. Why is that? In short, it’s because health systems negotiate with insurance companies (or with provider networks like Multiplan) to determine the final price that patients with that insurance company will pay for a specific service at a specific provider.

Health systems enter negotiations with their chargemasters, an itemized list of prices that the health system more or less conjures up. Insurers enter negotiations with any data they have about prices in other markets, as well as any data about what that health system is charging other insurers. (This is partially why the CMS price transparency rule that went into effect in January 2021 was such a big deal, and it’s also partially why Optum’s attempted acquisition of Change Healthcare, which has a lot of this data, matters quite a lot to hospitals.)

In short, the insurer-negotiated prices are often much higher than the cash-pay rates a hospital offers, which is fine when your insurance covers the cost. But for people with high-deductible health plans (HDHPs)—a growing percentage of Americans—this means they are stuck paying high negotiated prices until they meet their deductible. The median deductible for private American workers with HDHPs, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, was $2,000 in 2018.

However, providers also typically have a cash-pay option, often much cheaper than the negotiated rates (because, remember, hospitals enter rate negotiations with the artificially inflated chargemaster rates). Sometimes, the cash-pay option can be much cheaper than even the deductible a patient would have to pay.

The weird quirks of the cash-pay system are pretty well-known by healthcare insiders—one of my favorite happy hour conversations with healthcare people is hearing about how they’ve used cash-pay options to save thousands—but it’s a secret to most everyone else.

Sidecar: leveraging a loophole

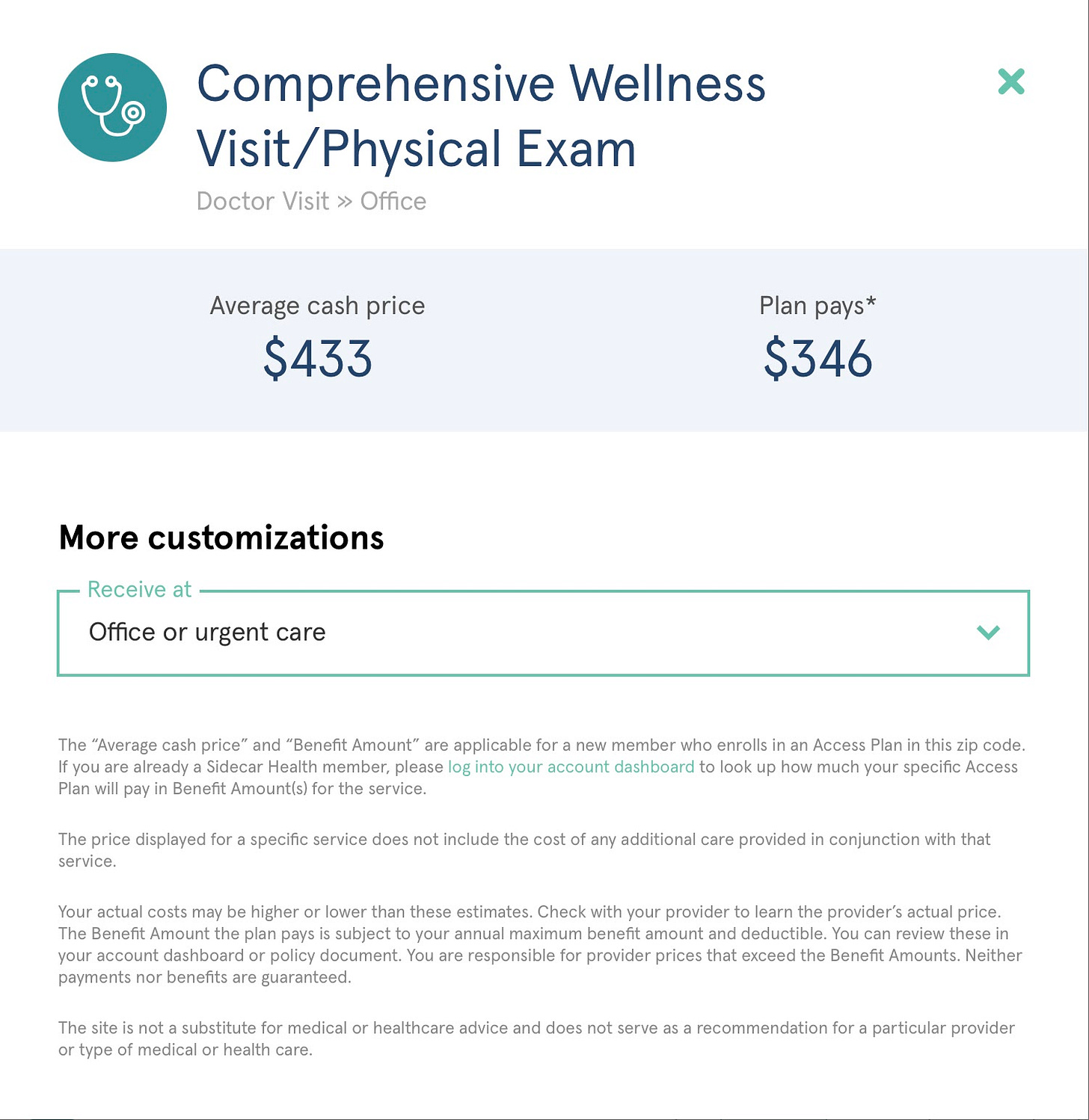

This is where Sidecar Health comes in. The company’s core business is a non-traditional Access Plan, which is fixed indemnity insurance. The Access Plan offers a fixed amount for most health services.

From the patient side, it works like this: A patient with Sidecar Health uses the app to find the cheapest cash-pay care and see how much of it Sidecar will cover. The patient then visits the doctor, pays the cash price either on their own or using the Sidecar Health Visa card, and submits the itemized bill to Sidecar within 30 days for reimbursement.

Because the Access Plan isn’t traditional insurance, Sidecar users can still be exposed to high prices—and without the safety net of an out of pocket maximum that even HDHPs offer. For Sidecar to be a good deal, users have to be generally healthy, not expect any big health events over the next few years, and be willing to take the risk to save money.

The premium amount also varies—Sidecar is free to charge different premium amounts based on health status because the Access Plan isn’t traditional insurance as covered by the Affordable Care Act (which disallows insurers from charging different amounts based on health status). Subsequently, according to Sidecar CEO Patrick Quigley, the average Sidecar user is 33 and makes between $45,000 and $75,000 a year.

A VC home run?

Sidecar is innovative, and it leverages the healthcare system in an interesting way, but I don’t see it becoming more than a sideshow in the insurance market. That’s because Sidecar’s market is limited to healthy young adults who are (1) shopping for themselves, (2) aware that Sidecar exists, and (3) willing to take a risk on a non-traditional plan.

For patients who meet these criteria, Sidecar’s model still requires a different workflow for the patient—you have to upload your bill within 30 days, or you’re on the hook for the total cost of care. This is different than how most patients conceive of insurance and, even if the app’s UX is good, a patient has to be unusually committed and health literate to take advantage of Sidecar.

Each of these requirements further narrows Sidecar’s available market, which makes it harder for the company to scale. I suspect that’s why Sidecar has recently begun expanding into individual marketplace plans (currently limited to Ohio) and early Medicare Advantage options, as well as serving self-funded employers.

Those plans are more traditional, and it’s unclear how Sidecar adds much value beyond the other newer, tech-enabled insurers. The company has more insight into cash-pay prices (and on that front, it fits into a general trend towards greater price transparency), and that could allow beneficiaries to do more price shopping—but patients generally don’t price shop, even when they have the option, unless they’re directly exposed to the full cost.

Conclusion

Healthcare is so big and so complicated that oftentimes people try to find a loophole in which they can build a company. Sometimes that works! PBMs (pharmacy benefit managers) only make sense because someone saw an opportunity for another layer of middlemen. But usually new healthcare companies end up being repeats of previous attempts, perhaps with better technology and more funding.

Sidecar is unique in that it actually leverages a kind of loophole. Patients who fit into Sidecar’s target demographics and who use the app the right way can save significant money on their healthcare. This alone is more innovative than what most of the insurers have so far managed to do around Medicare Advantage (although that might change, the market is still fairly new).

Unfortunately, however, I don’t see Sidecar’s loophole being big enough for a venture scale home run. Unless the company can figure out how to use its cash-pay price data to add significant value to other segments of the insurance market, like employer plans or, the big one, Medicare Advantage, even a useful product like Sidecar won’t gain much traction.

This information shouldn’t be taken as investment advice (obviously), and the opinions expressed are entirely my own, not representative of my employer or anyone else.