Botulism, recalls, and the open weaknesses in America’s formula supply

The structural flaws that make our formula manufacturing vulnerable

Those of you who don’t have a baby might not be aware of what’s happening in the baby formula market, but it’s bad news.

This month, the FDA, the CDC, and the California Department of Public Health announced that they were tracking and investigating an infant botulism outbreak linked to ByHeart formula. ByHeart is a VC-backed company with millennial startup branding that stands out among the other cans of formula at the store (and does extensive social media advertising). It’s also a formula clearly designed for crunchier, wealthier parents, costing around $1.75 an ounce compared to Costco’s Kirkland formula, which only costs about $0.69 an ounce.

In a triumph of public health monitoring, the California Department of Public Health’s Infant Botulism Treatment and Prevention Program (IBTPP) caught the outbreak fairly early, after only 13 suspected cases. Their monitoring picked up a rise in the background noise of infant botulism cases (of which there are an average of roughly 150-200 per year), noticing that from August 1 to November 10 alone, there were 84 infants who received treatment for botulism. Forty-three percent of those had received powdered formula, and 40% of those had had ByHeart formula, which was a red flag given ByHeart’s 1% share of the total U.S. formula market.

As of November 19th, the most recent day that the CDC reported data, there are now 31 total cases from 15 states, all of whom have been hospitalized. The IBTPP is offering free 24/7 consultation for providers caring for babies sick with botulism and is shipping no-cost treatment nationally. (Interestingly, the treatment was itself developed, licensed, and continues to be exclusively produced by the California Department of Public Health.)

ByHeart’s subpar response

ByHeart has handled the crisis terribly. I didn’t go to business school, but even I know that there’s a very common business school case study on how to handle a sensitive pharmaceutical recall. In 1982, someone added cyanide-laced capsules into Tylenol packaging in pharmacies around Chicago, killing seven people. Johnson & Johnson, the parent company of the Tylenol brand, quickly decided to recall all Tylenol in the market, reestablishing trust.

ByHeart did not do that. Instead, the company posted an Instagram video the same day as the CDC announcement with one of the cofounders arguing that “there is no reason to believe that infant formula can cause infant botulism.” After three days of denial and hinting that the third-party lab may have accidentally introduced bacteria into the formula during its testing, ByHeart finally issued a national recall on November 11th.

As late as November 19th, the company’s posts are still falling short for many former customers of ByHeart; an Instagram post received thousands of negative comments after ByHeart announced that its independent testing had found bacteria that can cause botulism in several cans of formula but didn’t reveal the batch numbers.

FDA formula standards

This recall comes at an interesting time in the baby formula market. The MAHA contingent at the FDA has drawn attention to the mandatory use of seed oils in formula in the U.S., where it’s used to increase the caloric and fat content of the formula, and to provide fatty acids essential for development. In March, HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. convened executives from several top formula makers to inquire about the formula ingredients and the state of the industry.

This meeting was quickly followed by HHS’s announcement of Operation Stork Speed, which ByHeart applauded, with commitments for more formula testing and a review of the nutrient standards introduced by the FDA in 1998.

Many of the MAHA movement point to the different standards that the European Union has for baby formula than the U.S. does. While many of the standards are similar, EU-regulated formula has more leeway for different options, including more options using milk fat instead of added vegetable oils. The EU also bans corn syrup in formula, while corn syrup is often one of the first ingredients in American baby formula. (In fact, most American baby formula contains added sugar, despite the American Academy of Pediatrics’ guidance to avoid added sugar for babies below two years of age.)

There are also heavy metals concerns: earlier this year Consumer Reports tested U.S. baby formulas and found that some contained toxic chemicals and PFAS that were likely inadvertently introduced during the manufacturing process.

Manufacturing challenges

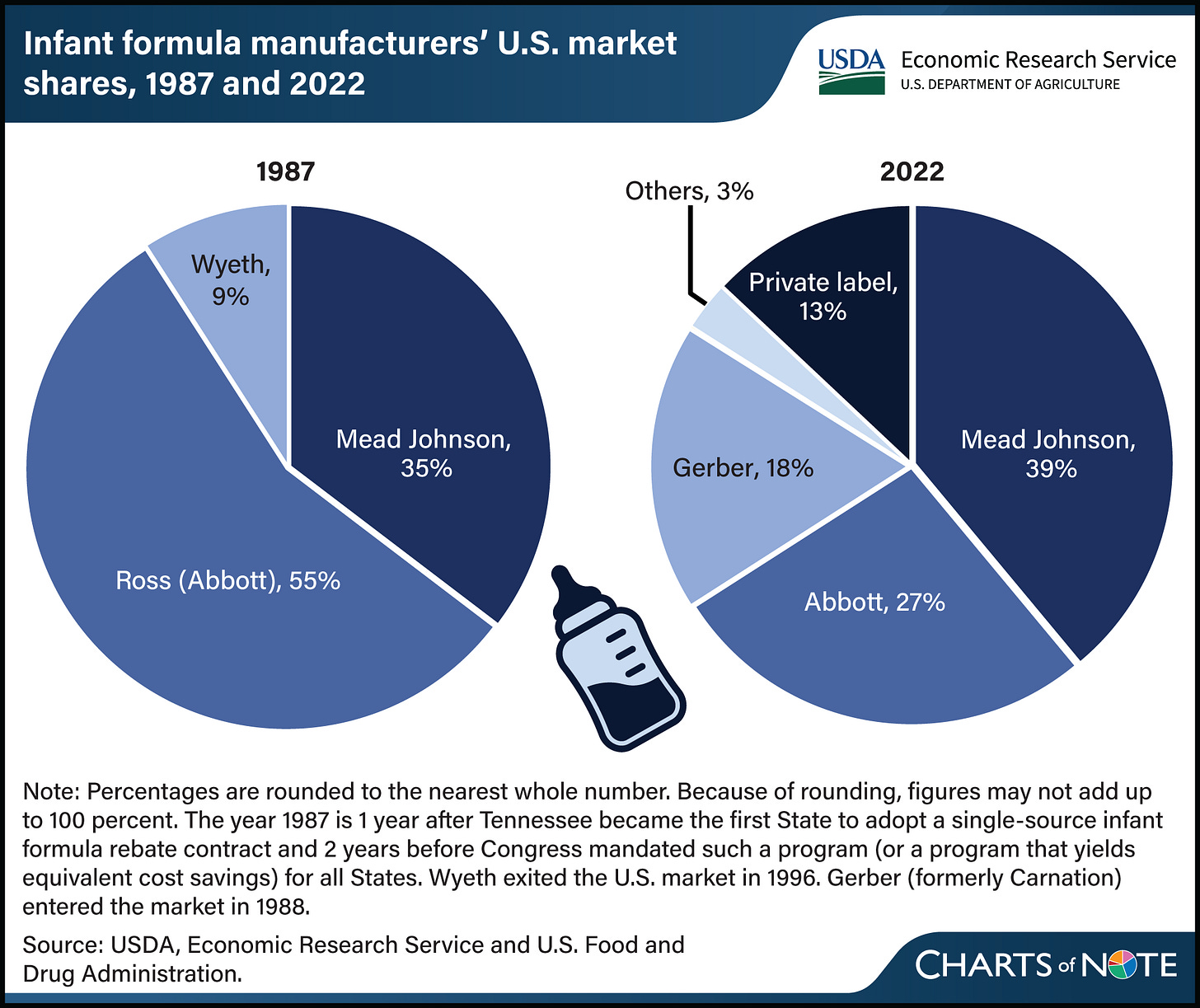

The baby formula story is also one about domestic manufacturing, supply chains, and food safety. The formula market in the U.S. is — no surprise — highly concentrated, with Abbott (which produces Similac, among other formulas), Reckitt Benckiser Group (which owns Mead Johnson, which produces Enfamil, among other formulas), and Nestle (which produces Gerber, among other formulas) controlling approximately 84% of the national market as of 2022.1

Unlike many other markets (including pharmaceuticals), the vast majority of the baby formula sold in the U.S. is also manufactured in the U.S. The U.S. is a net exporter of formula and imports only about 1.5-2% of total formula purchases. The U.S. also maintains a fairly high baseline tariff rate on formula products.

That said, the domestic supply chain is pretty weak, with only five manufacturers of baby formula in the U.S. as of 2022. Perrigo, listed under “private label” on the chart below, produces white labeled formula for store and other brands. The manufacturing dynamics are changing somewhat, with Bobbie, a new market entrant, opening a manufacturing facility in mid-2024 (while still partnering with Perrigo for the rest of its production). ByHeart was also a new manufacturer.

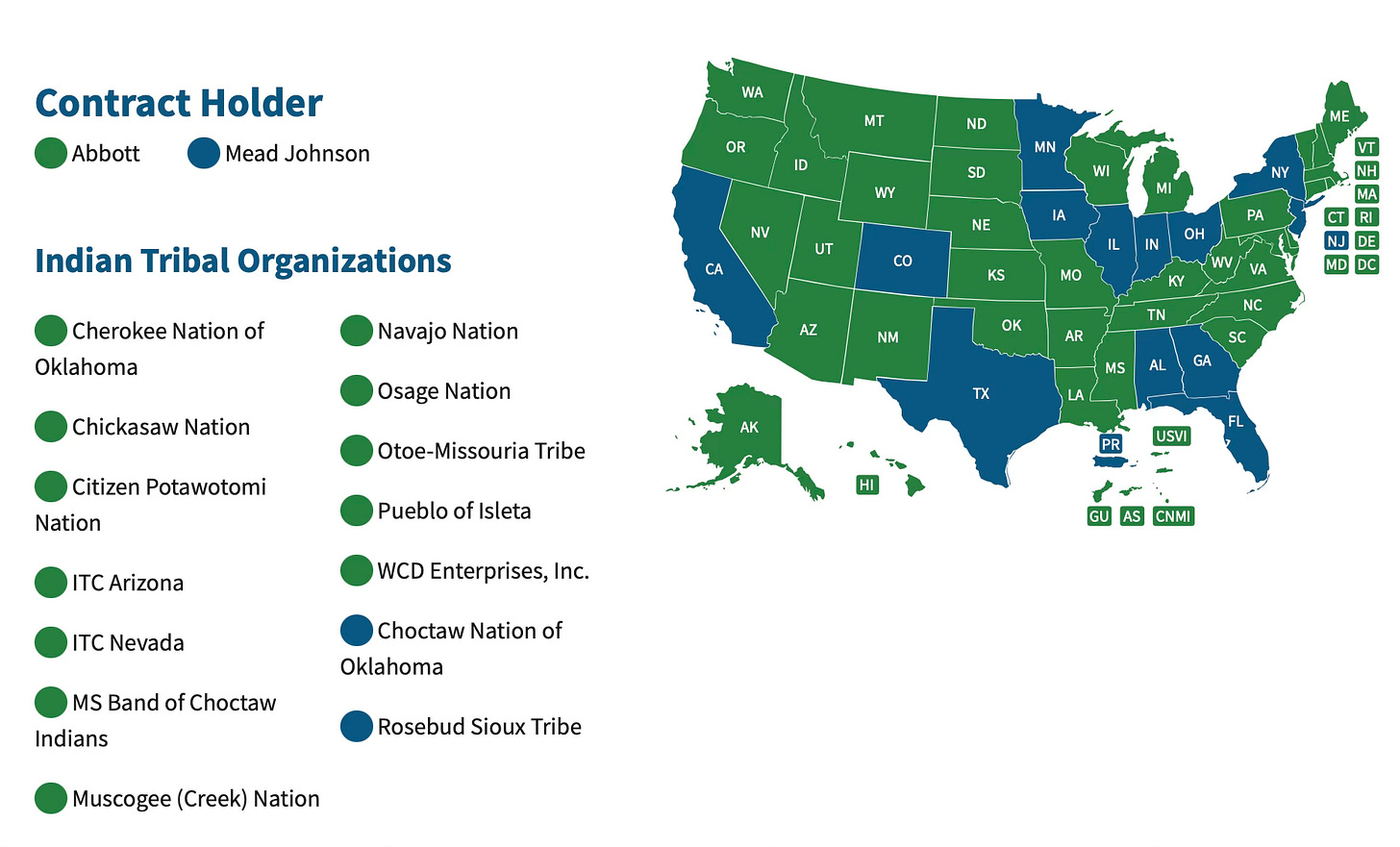

These market dynamics are, in part, entrenched by how formula is purchased in the U.S. Approximately 40% of all American babies get formula through WIC, the USDA’s supplemental nutrition program for women and children, making it the biggest buyer of formula in the country. WIC implemented a competitive bidding process for formula suppliers to provide a rebate to WIC participants in 1989.

This policy change possibly led to (or coincided with) a bit more diversity in the market, although, as discussed above, there are still only a few manufacturers of baby formula in the U.S. And Reckitt Benckiser/Mead Johnson and Abbott still hold the contracts in every state and tribal nation.

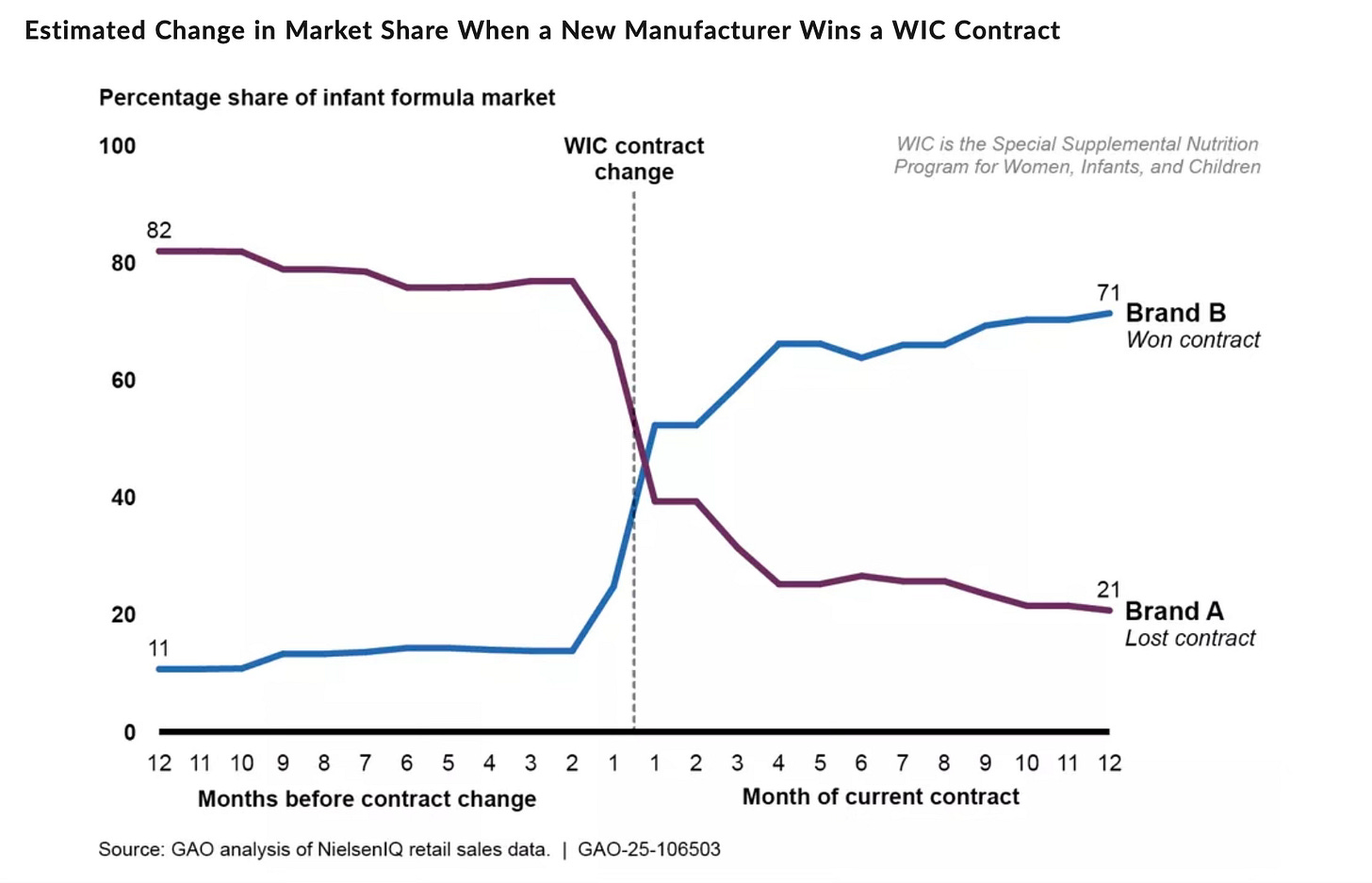

In early 2025, the GAO published a blog post discussing how the bidding process tends to stymie smaller market entrants. These market dynamics are likely why newer formula companies like ByHeart and Bobbie have focused on the upscale part of the formula market and have, at least in their earliest stages, relied on subscription models rather than commanding store shelf space and bidding for huge WIC contracts. But as the GAO noted, WIC contracts can change market share quickly; rewriting the rules of the bidding process could be a powerful policy tool to diversify the market moving forward.

The weakness inherent in the current market concentration most recently came to a head in 2022, when Abbott, which produces Similac and other formula types, recalled powder formulas manufactured at a Michigan plant after reports of several babies sickened by bacterial contamination. Because Abbott manufactures such a large proportion of the supply in the U.S., this recall had reverberating effects in the formula market, eventually leading to a national out-of-stock rate of 70%.

In response, the U.S. implemented Operation Fly Formula, which imported formula from other countries. Then-President Joe Biden also increased manufacturing capacity under the Defense Production Act, and Congress passed the Formula Act, allowing a brief period of duty-free imports of internationally produced formula. Finally, Abbott began manufacturing again.

Continued weakness

While MAHA focuses on the (probably justified!) issues with the nutrient standards of U.S. baby formula, there’s a bigger problem lurking: the concentration of the manufacturing supply chain and how any issues therein are likely to affect hundreds, if not thousands of babies in the U.S.

Bacterial contamination issues are not unique to ByHeart (although its poor response perhaps was), and protecting the most vulnerable members of our society includes ensuring safe and plentiful formula for the babies who need it. The concentrated manufacturing base leaves little margin for error; when something goes wrong, which it will, it’s the inevitable result of a fragile system.

If the formula supply is going to be truly dependable, we have to build that dependability into the supply chain, with a diverse base of manufacturers, strong FDA standards, and well-funded, knowledgable regulators providing oversight. And, perhaps, fewer Instagram posts from founders disavowing responsibility.