Company size is warping the healthcare market

Healthcare startups are stuck playing an Amazon HQ2 game

During my time in the private sector, one of the most frequent topics of discussion was the challenge facing young healthcare (and biotech) startups trying to sign contracts with some of the big players that control access to the market. UnitedHealth, Cigna, CVS/Aetna, Mayo Clinic, Intermountain Health, the list goes on — each of these logos is a prize for a startup to have on their website, and a rock on which many a startup ship is smashed.

You could argue (and I do) that each of these companies is too big, controlling access to the market in a way that locks out competitors and allows them to potentially steal competitive ideas from the startups.

The size of these companies might be warping the market in another way: the size of each individual contract is so large as to fundamentally change the dynamics of how they operate their businesses. For example, during Cardinal Health (a big drug wholesaler)’s earnings call in October, one of the analysts on the call congratulated the CEO and CFO on CVS’s recent acquisition of Rite Aid assets, purchased after Rite Aid declared bankruptcy (for the second time) in May of this year. Why, you might reasonably wonder, is an analyst congratulating the CEO of one company on the firesale of an unrelated company to another unrelated company? Well, because Cardinal is the wholesaler of choice for CVS, one of the biggest drug purchasers in the country — which got even bigger with the purchase of Rite Aid. Cardinal makes tens of billions of dollars from CVS, a number likely to go up with the Rite Aid asset purchase.1

This dynamic was also on display in November, when Eli Lilly announced that it was switching PBMs from CVS Caremark to Rightway, a much smaller PBM. This means that Lilly’s approximately 23,000-50,000 U.S. employees (for some reason different reported accounts vary on the number of employees at stake here) will be using the services of Rightway for their medications, a huge coup for Rightway.

Revenge?

Why did this shakeup happen? At least in part, it seems, the answer was revenge. In July, CVS Caremark (CVS’s PBM) decided to drop Lilly’s Zepbound (a GLP-1) from its formulary in favor of Novo Nordisk’s Wegovy (a competing GLP-1). Because Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk are in a fight to the death over which GLP-1 will capture the most market share, this was a huge loss for Lilly. So the company retaliated by switching PBMs from Caremark to Rightway.

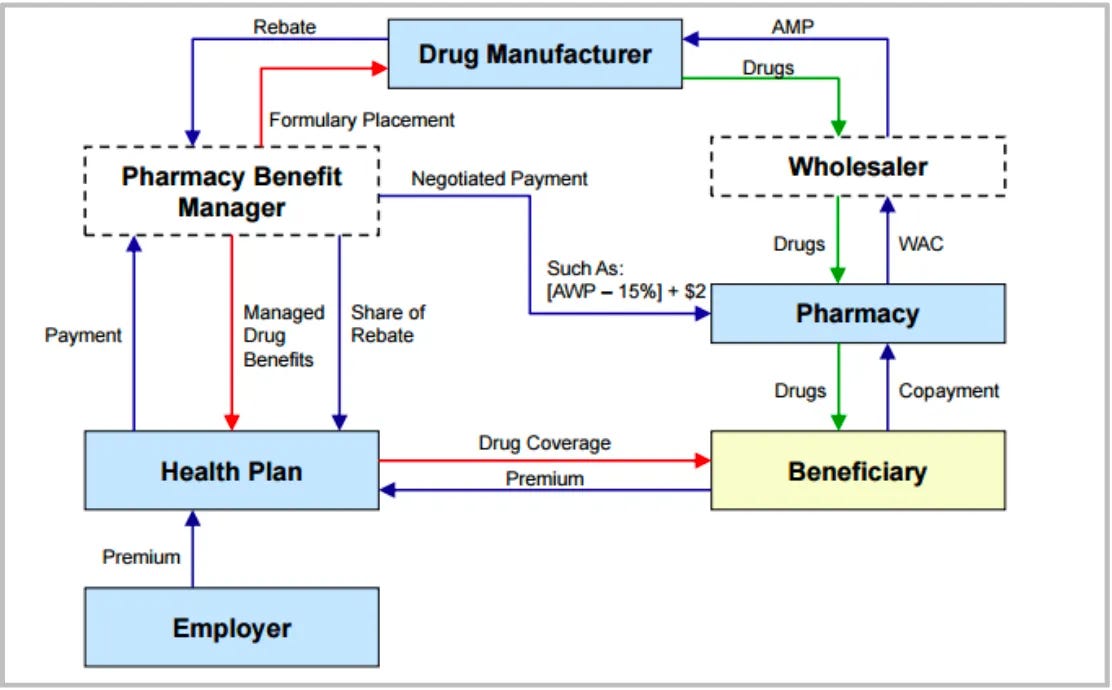

It might not solely be revenge: Rightway has an attractive model, intended to be more transparent than that of the traditional Big 3 PBMs, which control nearly 80% of U.S. drug spend (Express Scripts, owned by Cigna; CVS Caremark, owned by CVS; and OptumRx, owned by UnitedHealth Group). The Big 3, as well as most traditional PBMs, make money on the spread between payments from the insurer and rebates from the manufacturer (as enticements for placing preferred drugs on formularies) and the negotiated rate that the PBM pays to pharmacies.

Rightway makes money through a flat per member per month (PMPM) fee, passing along rebates to the employer that hires Rightway and paying the pharmacy a price calculated with a pricing model chosen by the employer. So, in addition to revenge, it might be Rightway’s approach that enticed Lilly; other major employers like Genentech and Tyson Foods have recently switched to Rightway. One other reason could be that Lilly saw an opportunity to align its public policy stance against PBMs with how it runs its employee benefits.

Surviving with a big contract

Regardless, the Lilly contract is big enough that Rightway likely made some promises to win Lilly’s business; for example, Genentech requested an accelerated implementation timeline, which Rightway delivered. This puts Rightway in a delicate position — the Lilly contract is a huge deal, and it will likely require Rightway to cater to Lilly’s every demand, even as Lilly can (relatively) easily play the field.

In this, the situation reminds me of the Amazon HQ2 search in 2017. For those that don’t remember, Amazon announced that it was planning to build a second headquarters outside of its main campus in Seattle. States and towns across the country put together pitch packages for Amazon, trying to entice it to come to their locality by promising tax breaks worth billions of dollars.

In the end, Amazon got data about localities across the country...and chose where it was probably always going to choose: Arlington, VA (this was the era when Jeff Bezos was considering being a Washington Man) and Queens, NY. These two localities promised, among other things, to subsidize the construction of a helipad so Bezos could helicopter in. Virginia also agreed to fight Freedom of Information Act requests on Amazon’s behalf and to give a cash grant premised on a future increase in revenue from a tax on hotel rooms that Amazon employees might end up staying in.

For a startup like Rightway (and to be clear, I have no insight into their specifics or any details about this deal), a contract with Lilly might alter the direction of the business altogether. They will likely have to hire business development people, account managers, and sales representatives, all for Eli Lilly. If Lilly changes its mind about using Rightway, it fundamentally shifts Rightway’s funding and survival prospects — making contracting in healthcare right now a very delicate dance.

Healthcare startups are in a difficult position

It’s not just Rightway, either. This dynamic is facing most healthcare startups right now as they have to decide what big contracts are worth going after, and which big partners are trustworthy in the long-term.

Amazon used its power to get tax breaks and spin up a bunch of cities…just because it could. Eli Lilly is switching PBMs because, in part, it’s mad at Caremark and because it can. If Caremark promises to go back to Zepbound, will Lilly switch back? Could it leave Rightway in the dust? And: what does this mean for startup founders and employees? It certainly makes things more difficult.

A pharmacist colleague who reviewed this article noted that the financial dynamics of major purchasers like CVS from wholesalers is complicated — because the major purchasers have so much leverage over the wholesalers themselves, the purchasers can exert downward pressure on wholesaler prices to the point of affecting profit. For example, when OptumRx shifted from Cardinal to McKesson, Cardinal noted that the OptumRx contract had been 17% of revenue but only 4% of operating profit.

This is a great article, Olivia, and a keeper. I've read it, now I'll study it. Thank you!