Hybrid care models and the future of primary care

I’m being optimistic about wearables

Per the saying about how most meetings could be emails and most emails could be phone calls, I sometimes wonder if a specific post should just be a tweet thread. This might be one of those—but you’re getting it anyway, because my company announced a merger this week!

Before I get into my topic, I do want to add an actual tweet thread that I did, because it’s relevant to my recent newsletter about web3.

In short, I got some good feedback that the most useful applications of web3 will be in leveraging DAOs for natural flywheels, like crowdfunding basic scientific research with the DAO co-owning any commercially viable product of that research. It’s still possible that electronic health records make sense on chain, but the incentives aren’t structured as neatly. As I said in the thread, I’m always looking to learn more, so let me know if you’re working on anything in the web3/healthcare space!

The topic for today: hybrid telehealth models and the future of primary care.

Steve Kraus, Sofia Guerra, Andrew Hedin, and Morgan Cheatham of Bessemer Venture Partners wrote in their 2022 predictions post that:

We expect healthcare companies that provide an omnichannel patient experience, integrating online and offline care, will more likely succeed longer term compared to one-modality options.

In other words, basic telehealth has become commoditized, pushed along by the pandemic and the mass adoption of video chat across work, community, and healthcare applications. It’s possible to video chat for support groups, tax preparation appointments, and (terribly awkward) happy hours. Meeting with your physician online was novel three years ago; it’s quotidian now.

At the same time, the existing telehealth offerings are pretty basic. The traditional doctor’s visit is no different for being online. And without much innovation in what it means to see a doctor (the modality in which you’re “seeing” them notwithstanding), many current telehealth options are stuck replicating the fragmented and frustrating experience of traditional primary care.

The patient may not even be able to remain at home. There is no way to complete basic imaging like x-rays or procedures like wart removal at home. (Oscar does offer at-home vitals monitoring kits and in-home labs for their primary care patients.)

Bigger primary care companies are tackling this problem by developing referral relationships with health systems. In 2019, for example, One Medical announced a partnership with Mt. Sinai, naming Mt. Sinai the preferred healthcare system partner of One Medical in the Greater New York area. One Medical has other health system integrations around the country, including with UCSF Health, Dignity Health, and Emory Healthcare. Other models, like Oshi, Oula, and Keeps Hair Restoration (at my company) are working to bridge the telehealth/in-person flow for specialty conditions and still provide a seamless patient experience.

At the same time as virtual care companies are trying to figure out hybrid options, there is still a major gap between care that can be done at home and care that is being done at home.

This overlaps with a quote I read in a16z general partner Julie Yoo’s recent interview with STAT News’s Mario Aguilar. She said:

The successful efforts will be those who actually implement true primary care. What I mean by that is a lot of the initial generation of telehealth companies that people thought were primary care were actually urgent care. They were highly transactional. They focused on very low acuity events that could be treated through telehealth and did not focus on longitudinal relationships with the patient or any of the downstream stuff that happens when patients really get sick.

(Making Julie’s case for her, a few companies have tried to draw a line between virtual primary and virtual urgent care and inadvertently highlighted how similar the two offerings are. Oscar, for example, which started offering free virtual primary care in 2021, differentiates between virtual primary care and virtual urgent care by how quickly the patient wants the appointment. But given that virtual primary care can be available same-day, it’s unclear to me what this differentiation looks like in practice.)

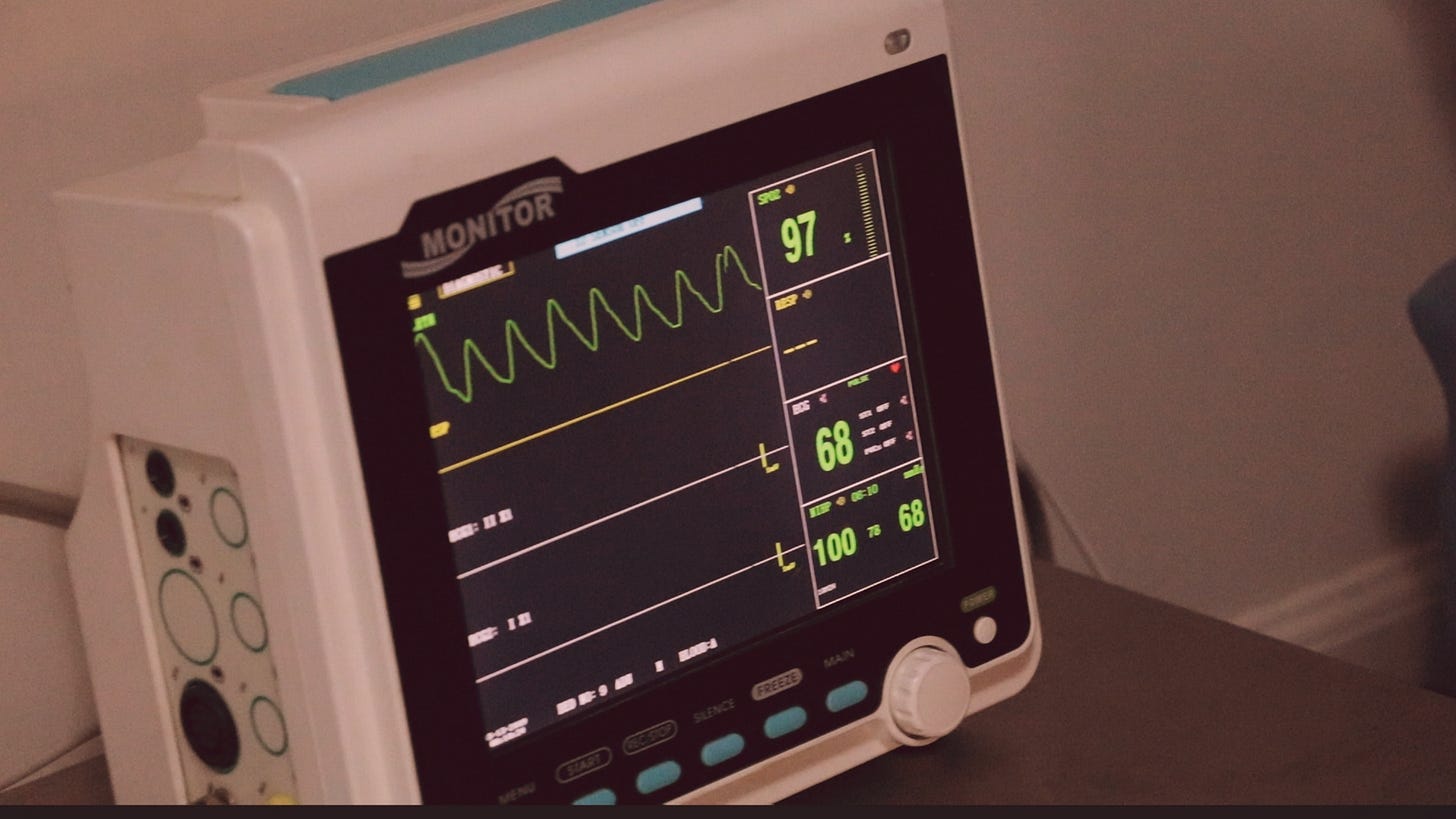

A lot of the ideal of true primary care—longitudinal patient tracking, necessary cancer screenings, lifestyle coaching—demands an in-person component. The provider may not need to be in person, but the data required to really improve a patient’s health over a lifetime has to originate with the patient’s physical body. That’s where remote patient monitoring and wearables could be helpful, that’s where seamless hybrid options could allow patients to move in and out of virtual and brick-and-mortar locations—but that’s also far more complicated than offering one-off, urgent care-adjacent telehealth visits.

Partnering with health systems is one way to help bolster basic primary care services, things like flu shots and mammograms; it could also prioritize procedures at the expense of more longitudinal care and coaching.

At least in the U.S., we’ve never really figured out how to do the ideal version of primary care in a scalable way. To be optimistic, I’ll say that it could be because we’ve never had the technology or computing power to help patients know themselves and live healthier lives. And now, even as that technology and computing power is starting to exist and improve every year, we’ve never been able to successfully integrate it into a scalable care model. All of this is possible—but it will be a very interesting challenge for virtual care companies and health systems over the next few years.

This information shouldn’t be taken as investment advice (obviously), and the opinions expressed are entirely my own, not representative of my employer or anyone else.