Is China really destroying Boston biotech?

Competition and stagnation

As I wrote in May, I see this newsletter as covering a few specific things: how the business of healthcare is changing, how the politics of healthcare is changing, and how the state capacity to achieve these changes is keeping pace (insofar as the state is affirmatively making decisions about healthcare…which is not really the case right now, beyond unnecessarily disruptive tweaks to the vaccine schedule).

One of my areas of interest re: the business and politics of healthcare is the United States’s ongoing geopolitical competition with China. This is certainly outside the mainstream for many in the healthcare industry, but I would argue that it’s worth paying attention to, as it will affect both the business and the politics of healthcare.

Before we all closed our laptops for the winter holiday break, the Wall Street Journal published an article about how the Boston biotech sector is struggling. The article noted that hiring is down, attributing it to research funding cuts at the federal level, and it also highlighted a PhD student, raised in Hong Kong, who is considering taking a job in China because of the tough market here.

This article sparked controversy for a few reasons: did it correctly identify the source of the downturn in biotech? Is it even a downturn, or just a correction from an overly hot 2020-2021? And — the fear that’s been in the minds of many biotech investors and founders — is China truly drawing closer to surpassing the U.S. in this sector too?

The changing biotech market

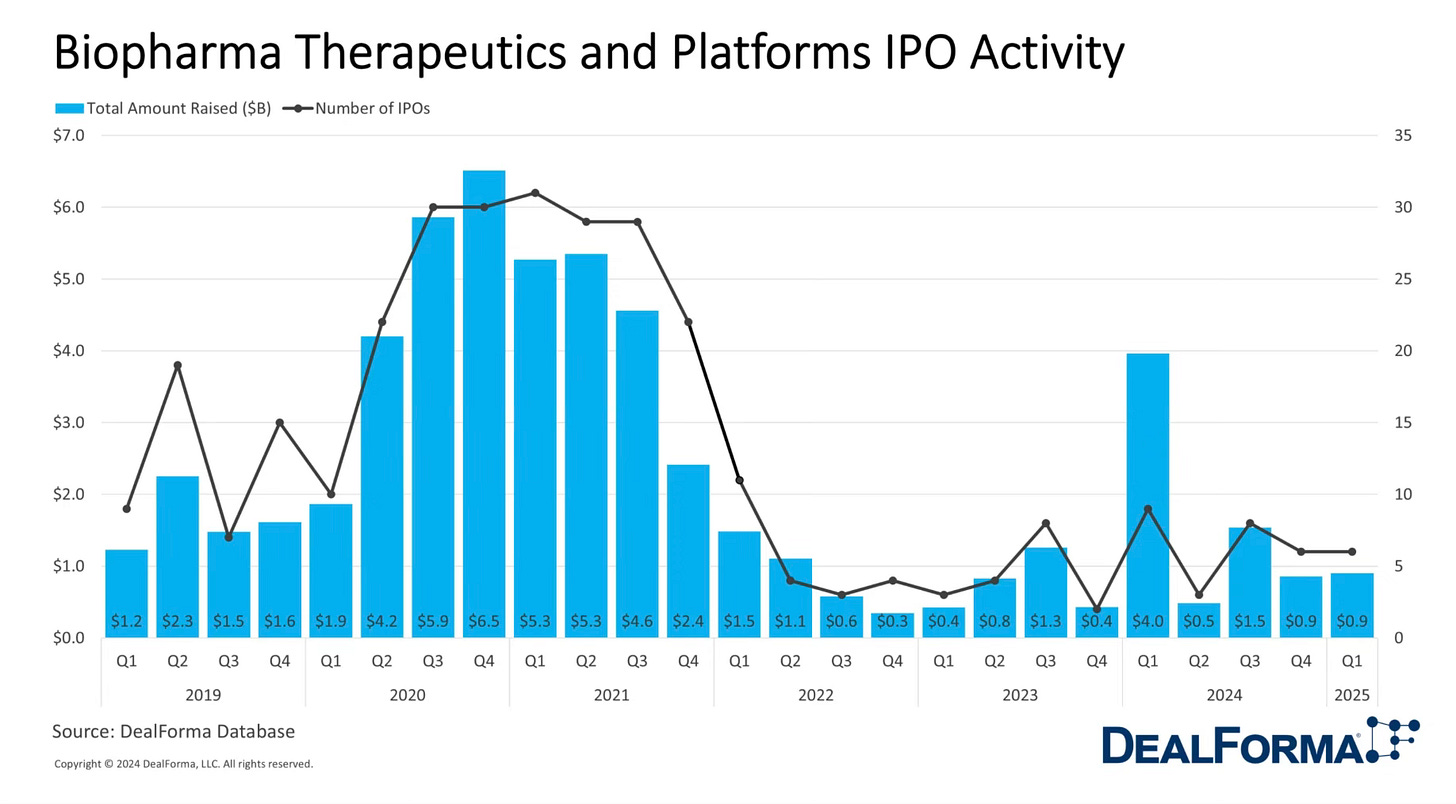

The mini boom and bust cycle that biotech experienced the last few years was the first boom that I was in private industry for — and it felt crazy. There was a sense that no investment could miss, that all drug targets were going to hit their marks. Then AI became more of a consumer product and it seemed like all human disease would fall before the mighty AI’s ability to generate drug candidates of interest.

Of course, none of that was ever totally true. And the biotech IPOs never really happened; in fact, saying “next year the market will come back” became such a common phrase that I started to block it out.

In 2022, the Fed began raising interest rates, much of the biotech cash dried up, and some key startups failed. The NIH cut billions of research dollars. The investors that had flocked to the space departed in droves. The remaining investors painted it positively, saying that this belt tightening would reveal who was truly good at evaluating a solid candidate compared to those who were just chasing venture dollars. The market corrected.

China’s investment in biotech

Meanwhile, China has been coming after biotech like a heat-seeking missile. The Chinese Communist Party develops regular Five-Year Plans outlining what the next areas of focus and investment will be. The Fourteenth Five-Year Plan, published in 2021 and covering 2021-2025, stated a desire for China to become a world leader in cutting-edge biotech.

The recent history of biotech in China follows a path that has happened with other sectors, including electronics. China originally served as a manufacturing partner, with willing employees and factory bosses who could turn out components to detailed specification. Eventually, the on-the-job training required to turn out these components also produced highly skilled workers and managers who were available for hire for Chinese-led innovation. Then, China became a world leader in creating its own technology, manufacturing it, and exporting it.

Similarly, China has been a manufacturing partner for Western pharma and biotech companies for years. China is the source of an estimated 80-90% of all U.S. generic pharmaceuticals (the number is almost impossible to calculate because the FDA doesn’t track the source of the ingredients that go into pharmaceuticals, but nearly every generic has a dependency on China for some part of the supply chain).

In recent years, China has moved up the value chain, becoming a manufacturing partner for synthetic DNA sequences. Now, companies like WuXi AppTec do contract research, development, and manufacturing as a service. WuXi’s tagline is that it’s available for “DNA to IND” — meaning that it has the ability to help clients generate a synthetic DNA sequence of interest for research purposes, test that sequence, edit it if necessary, and carry the process all the way through to the investigational new drug application that companies file with the FDA for clinical trials in the U.S.

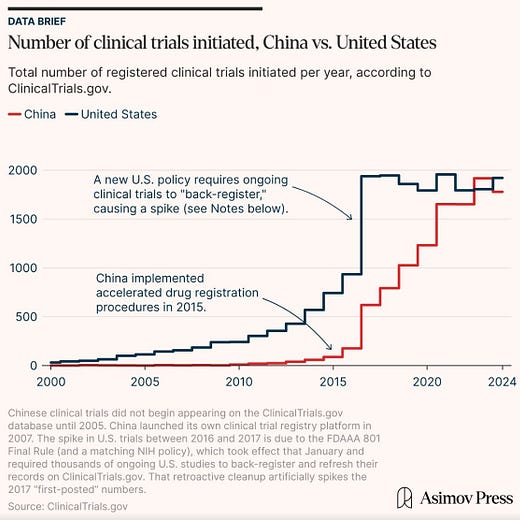

China’s investment in the space has borne clear fruit. Prior to 2015, the Chinese Food and Drug Administration suffered from corruption and incompetence. Starting that year, the CFDA (now called the National Medical Products Administration, or NMPA) began a hiring wave, cleared a massive backlog of new drug applications, and adopted clearer regulations.

Part of this process was a 2018 shift to an “implied license” system, meaning that Chinese regulators allowed IND (investigational new drug) applications to move forward if regulators did not raise objections within 60 days. For drugs developed outside China, IND approval took an average of 18.5 months before December 2016. IND submissions after December 2016, in comparison, took an average of 8.6 months (as of May 2018, the latest date I could find a source for).

Chinese drug development is also much faster because of the size of the patient population and the centralized nature of the health system, allowing physicians to recruit for drug trials much faster — half the time than required in the U.S. for conditions like cancer and obesity.

As a result, China’s biotech companies have taken off. In late 2024, Summit Therapeutics announced that its drug candidate, licensed from the Chinese company Akeso, far surpassed the leading U.S. drug Keytruda’s ability to slow tumor progression in lung cancer. U.S. companies began rushing to the Chinese market to acquire or license their drug candidates for their portfolios. And China is investing in and encouraging more development, including among younger research teams. At the 2025 synthetic bio “Olympics,” the International Genetically Engineered Machine competition, or iGEM, 50% of the teams were Chinese.

Why does this matter?

The loss of a thriving American biotech sector means the loss of homegrown novel therapeutics and treatments for conditions that affect all of us. And even though the U.S. pharma sector has real problems with stagnation (namely: lessened spending on R&D in favor of stock buybacks), the basic research and legwork that these companies do has the potential to create the next penicillin or GLP-1.

Why does it matter if China takes the lead? As with the other sectors where China has surpassed the U.S. on research, development, and manufacturing, the loss of the American ability to do these things means we lose all of the side benefits that go with it — jobs, process knowledge, downstream research effects, and more. There are the geopolitical concerns, and there are data concerns.1

And as Drew Endy and Mike Kuiken, both of the Hoover Institution, recently wrote in an op-ed in the Boston Globe, this matters long term as well:

The first nation to make routine the building of cells will own an “operating system” for life, coded in DNA rather than ones and zeros. The first nation to establish biomolecular standards — the “weights and measures” underlying the bioeconomy — will have a persistent competitive advantage. If we miss solving biotechnology’s coordination problems, catching up later will become almost impossible. Without question, the United States can do these things, but a sustained whole-of-nation effort is required.

Editorial note: The original version of this piece stated that companies like WuXi AppTec have “the ability to help clients generate a DNA sequence of interest for research purposes.” It has been updated to specify that WuXi AppTec generates synthetic DNA sequences for research purposes.

Nice deeper look root-causing whether flattening U.S.-based biotech R&D investment is related to the market over-heating or missed opportunities to build more sustainable domestic development models.

I appreciate your clarification re: the "centralized" versus "decentralized" nature of the Chinese national health system. Yes, they've very effectively overhauled clinical trial design, approvals, and data-sharing--as well as communication channels with regulators. However, I think the word you may be looking for is "layered". The U.S. has a hyper-transactional, fragmented healthcare system. China's national health 'scheme' is pay-to-play, with the basic tier covering 95% of health costs, but it's up to patients to add specialty care a la cart, layering this on top of their existing plan(s). Agreed that their network design socializes patients to seek care locally, which is another issue unto itself.

One counterpoint I'd like to offer: I'm not sensing that China's gain in biotechnology is a net loss for the U.S. Meaning, I would like to see more partnership, shared learning, bilateral hiring agreements, etc. I don't think innovation in medicine can be an "us" versus "them" game moving forward.

This is well written and interesting and I appreciate you writing it as I found it informative and was only vaguely aware of this angle vis a vis us Biotech struggles. I would have one nit pick though I think there may be a slight error in the essay, and that is here: "Chinese drug development is also much faster because of the... the centralized nature of the health system", there system, in relevant regards, is actually more *decentralized* than our is (well, thats certainly the case generally, but I think it may be the case here on this narrow specific as well)

China’s delivery/financing is often locally governed and administratively fragmented, but trial recruitment can still be faster because patients are concentrated in huge tertiary hospitals, physicians can recruit from very high-throughput clinics, and regulatory/contracting friction is just generally lower anywhere you are. I think that “centralization” isn’t the thing here; throughput + friction is.