The challenge of building a specialty EHR

And what happens if companies consolidate?

Thank you to everyone who wrote in with new topic ideas, they were all really great, and you’ll see those ideas fleshed out over the next few weeks. This topic, for better or worse (probably worse) is all mine. Also, it’s shorter than normal, because we got a puppy, and she is equal parts chaotic good and chaotic evil. 100% chaos.

Existing electronic health records (EHRs) are bad. Two weeks ago, I wrote about how the main inpatient EHRs, Epic and Cerner, have long-term contracts with hospitals, have no pressure to innovate, and probably aren’t going anywhere anytime soon.

(I say “probably” because a coalition of health systems, called Truveta, recently announced plans to build their own patient data aggregation tool, thereby going around Epic and Cerner’s intentional lack of interoperability. This coalition is centered around data aggregation and research, so it’ll be interesting to see how this evolves.)

Outpatient specialty EHRs

But what about outpatient care? Many independent practices, both primary care and specialty, use other EHR software that’s more tailored to what the practice needs.

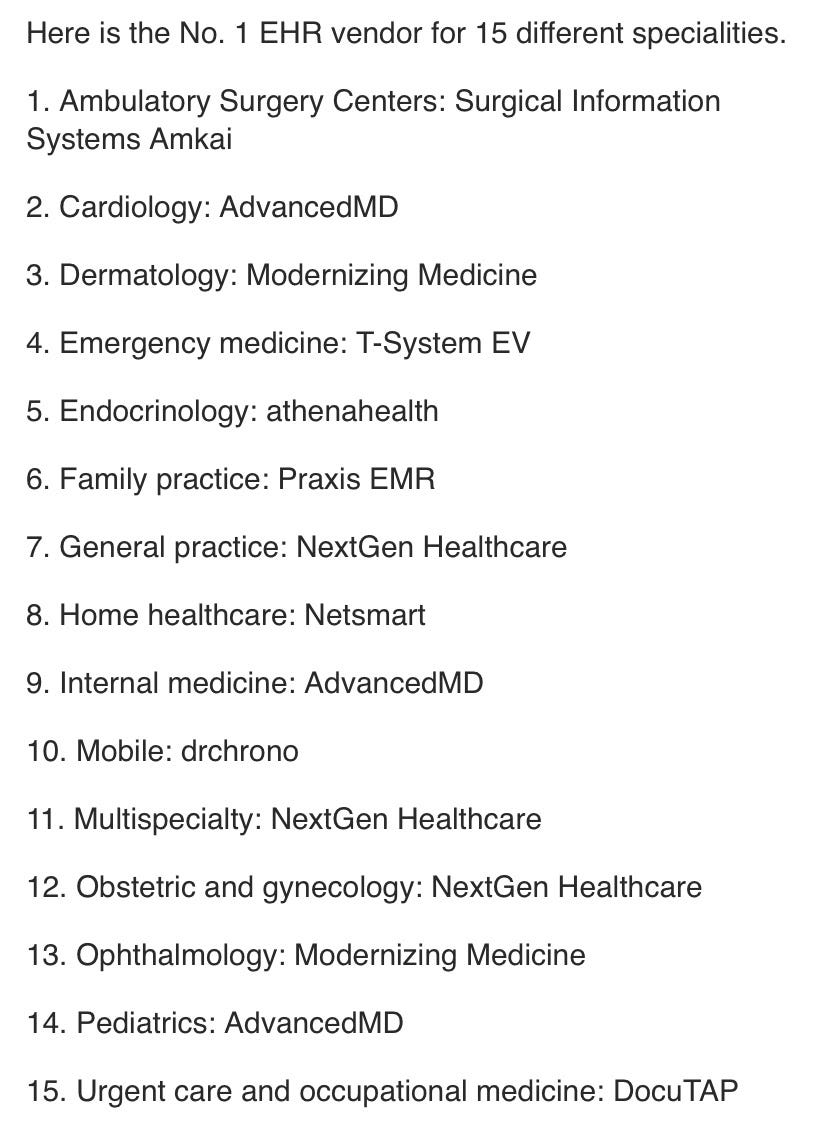

These can include PointClickCare, athenahealth, and Elation, among others. There are so many that Becker’s Hospital Review has a list of the top 15 by specialty, with limited overlap:

Different practices adopt different EHRs to fit with their practice and specialty needs, as well as any unique billing or referral situations they may have.

“Basic functionality just to recognize that a patient is a child”

To get a sense of what goes into adapting an EHR to a specialty, I like the example of the effort behind developing a pediatric-specific EHR.

EHRs were so poorly adapted to pediatric needs that one of the core problems was, as Community Care of North Carolina (CCNC) Deputy Chief Medical Officer Marian Earls told EHR Intelligence, “[w]e’re still asking for basic functionality just to recognize that a patient is a child.”

To tackle this problem, the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHQR) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) developed a standard format for pediatric EHRs, called the Model Child EHR Format.

Health entities like CCNC, Duke, and Intermountain Health evaluated the format with a gap analysis, eventually listing the need for 560 requirements to fill gaps in approximately 25 topics. After the gap analysis, CCNC began working with EHR companies and pediatricians to develop more improvements and put them into practice.

Besides the functionality to recognize a child, the coalition's recommendations included children-specific asks, like the addition of growth curves and documentation for caregivers. The team also requested implementation of data tracking social determinants of health.

Digital health EHRs

Even getting an EHR to recognize that a patient is a child is challenging—so digital health companies that are providing a mix of services often have to develop their own EHRs.

Think about Oula, for example (full disclosure, I don’t have insight into whether the company developed its own EHR or not): The company provides in-person and virtual visits, remote monitoring, doulas and lactation consultants, and the option to give birth at a hospital in New York City. The more conditions a company treats, the broader and more adaptable the EHR has to be.

This is more speculation than anything, but lately I’ve been wondering what will happen to all of these one-off EHRs if the predicted digital health consolidation takes place. Will merging companies…also merge their EHRs? Have these companies inadvertently replicated the interoperability problems that plague hospitals using legacy EHRs like Epic and Cerner?

One survey published in Health Affairs found that, of the 88 hospitals that were acquired between 2012 and 2014, the majority—nearly half—did not switch to the EHR of the acquiring health system. Granted, this data is now old, but it’s a testament to the complexities of merging or transferring EHRs. What will happen to companies that have built their own?

Conclusion

I’m not the first person to have these questions. There are several companies that exist to make the integration and development process easier. Redox, founded in 2014, uses a “developer-friendly API” to connect EHRs with digital health products. Zus Health, founded in 2020, offers a portfolio of software tools and services for companies to build healthcare records and experiences. As Zus founder Jonathan Bush said in a press release announcing the company’s Series A raise, “We think healthcare is ripe for a platform company that lets everyone write their own front ends, while sharing appropriate data in the back.”

And I haven’t even gotten into the concept of putting healthcare data on the blockchain, mostly because I can’t imagine the technology achieving widespread healthcare industry adoption any time soon.

The early stirrings of a new model of patient record keeping—something easily customizable, easily accessed, and readily available—seem to be here. But the existing system is entrenched, the EHRs are already built and siloed, and I don’t see this changing any time soon.

This information shouldn’t be taken as investment advice (obviously), and the opinions expressed are entirely my own, not representative of my employer or anyone else.

Nice article 👍

For what it's worth, all Epic and Cerner instances are live on Carequality and Commonwell, which means they have interoperability between all sites to retrieve clinical documents. Not perfect, but "Epic and Cerner’s intentional lack of interoperability" isn't really a fair representation of where they are today