I recently talked to Stacey Richter of Relentless Health Value about the need for and industry barriers to building a patient-focused specialty pharmacy. You can listen here or wherever you listen to podcasts.

If you follow the news, you know hospitals have been weathering a rolling crisis for nearly two years. At first, they were managing a lack of PPE and more COVID patients than hospital beds. Then, hospitals were the frontline of the vaccine rollout, a hefty job that included patient outreach, vaccine education, and all of the complex cold chain requirements that the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines demanded. Hospitals also found themselves at the epicenter of protests from the outside population, convinced that healthcare workers were lying about the safety of the vaccine.

But in managing all of these crises, hospitals placed a heavy burden on their workers.

And not only is the life of a COVID-era healthcare worker stressful and dangerous, but hospitals have done little to alleviate ongoing issues with healthcare work that pre-dated COVID.

The hours are long and variable, women and minority workers contend with micro-and macroaggressions, the pay—particularly for nurses and residents—isn’t great. As if to underscore how challenging these jobs can be, the New York Times recently reported on the fertility challenges faced by women physicians, likely tied to a later age at first pregnancy, a stressful job, limited sleep, and poor diet.

Now, as some healthcare workers decide they’ve had enough and others leave in search of better pay, hospitals are not only overrun with a fourth wave of COVID patients, they’re also suffering a severe staffing shortage.

The crisis isn’t new

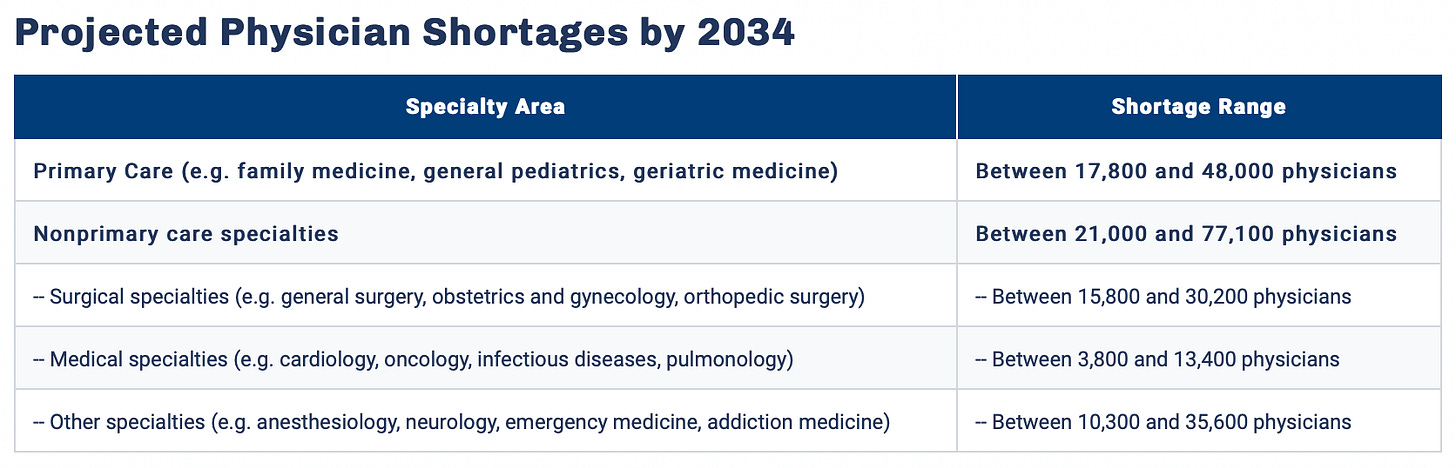

Even before COVID, the U.S. was experiencing a healthcare worker shortage, driven by a variety of factors including demographic shifts, as well as active discontent among healthcare workers.

As baby boomer healthcare workers begin to retire, the healthcare system is losing a large number of staff. At the same time, an aging U.S. population needs more medical care.

The thornier, although ultimately more actionable problem, is staff discontent.

The medical education model hasn’t really changed in more than 100 years. In 1910, the U.S. began to reorient and standardize medical education away from unlicensed, traveling doctors and towards the German model of standardized, science-first training.

This worked fine enough in the early 20th century; groups of all-male residents used to literally reside in the hospital in which they worked. But American work and family culture has changed, even as the residency process has stayed the same. Now, requiring fourth year medical students to take whatever job they win in the Match process seems harmful or even abusive. It’s clear that hospitals can exploit highly trained residents by demanding long hours for little pay—and residents can’t leave unless they want to forfeit the training process.

Even before COVID-19, healthcare workers were beginning to agitate for change. I heard well-respected physician leaders repeatedly call for doctors to go on strike (even if in a symbolic way) back in December 2019. Around then, the group Medicine Forward formed to provide physicians with some kind of ability to organize.

But it was accelerated by COVID

Early in the pandemic, the long-simmering crisis of healthcare worker discontent exploded. Healthcare workers were asked to use garbage bags as personal protective equipment. Workers with no training in infectious disease or ICU care were reassigned to COVID wards. Hospital staff were confronted with traumatizing scenes of illness, even as they had to keep pushing off their own mental health needs.

Despite the obvious need for compassion and additional support, most hospital leadership fell back on their position that healthcare workers should prioritize taking care of patients at the exclusion of all else.

In April 2020, when many residents at NYU Langone signed a letter asking for hazard pay, hospital leadership denied their request—and accidentally forwarded internal emails to the residents, questioning their loyalty to patients and accusing them of financial greed.

Even as the pandemic rages on, most hospitals have been unwilling or unable to take a proactive stance in supporting their workers. The result is that the portion of healthcare workers that have the most flexibility in finding a new job are exercising that option.

Data recently compiled by Gist Healthcare found that nearly a quarter of nurses in the U.S. are considering leaving their jobs. The most important influence behind their decision to leave is short staffing, followed by workload intensity and emotional toll. Hospitals are relying far more on travel nurses than they were in March 2020, and some are offering five-figure signing bonuses, a measure of their desperation for workers.

Suddenly hospitals are rewriting their budgets to pay more for nursing talent. Of course, it would have been simpler to support them more, emotionally and financially, in the first place.

Until hospitals make dramatic changes, the staffing crisis will only get worse.

I’ve been writing about discontent among healthcare workers as long as I’ve been putting out this newsletter. My very first post was about doctors struggling through the pandemic, and I wrote a follow-up in April 2021. The conclusion both times: Healthcare workers are not okay.

What has changed since April, though, is that the pandemic has become a war of attrition. Healthcare workers are powerless to force people to get vaccinated, and they’re powerless to push back against anti-vax misinformation. All they can do is keep treating the people who get sick.

In lieu of genuine support from the hospitals that employ them, healthcare workers are beginning to more publicly express their concerns. Unions saw an uptick in interest from healthcare workers during the pandemic. I’ve seen much more public discontent from healthcare workers I follow on forums like Twitter. Eventually, workers may be able to force hospital leadership to make changes.

Hospital leadership needs to be proactive

Many hospitals use their nonprofit status, their role in the community, and their sometimes-tight budgets as a way to delay significant change and curtail innovative ideas. They throw up their hands, point to the way things have always been done, and refuse to implement common sense changes to improve their staffs’ quality of life.

But now it’s time for hospitals to be proactive. As one resident told the New Yorker in 2020,

It can’t be business as usual anymore. I think this moment makes that clear. If we are not well, and we are not cared for, then we can’t do our job.

There are relatively simple, obvious reforms to make: Adding pumping rooms, integrating maternal and paternal leave policies, adding holiday pay, making schedules further in advance, paying high enough salaries to attract and maintain adequate staffing numbers.

There are also deeper reforms, ones that may only bear fruit years in the future but which are essential to continuing to attract highly motivated and skilled individuals into healthcare.

Medical schools should cut back on onerous, unnecessary requirements (sorry, doctors don’t need two semesters of calculus), hospitals should pay residents more, the number of residency slots should be expanded. The Match process should be reworked to allow residents more choice and require hospitals to compete more on working conditions.

Conclusion

I’m very optimistic (maybe too optimistic) about what the present moment means for the future of hospital staffing. Much like telehealth and interstate physician licensing reform—things that advocates had been pushing for years—were suddenly implemented during the pandemic, the present moment provides an opportunity for change. Hospital leadership should take a hard look at what support they’re providing and figure out how to provide much more. The medical education system should take this inflection point as a sign that the entire education and training curriculum needs to be revamped. The crisis demands it.

This information shouldn’t be taken as investment advice (obviously), and the opinions expressed are entirely my own, not representative of my employer or anyone else.