Hims & Hers and the end of GLP-1 compounding

It was inevitable

The New Yorker dubbed 2023 as “the year of Ozempic.” It wasn’t the year that the drug was invented or first given to patients, but it was the year that it exploded into the public consciousness.

Ozempic is part of a class of drugs called GLP-1s, which I won’t get too deep into, as many people are burned out from even hearing about GLP-1s from 2023 (me included). How many times can you hear about how the underlying research came from a Gila monster’s saliva? Every popular podcast had at least one episode on this topic.

Compounding pharmacies

But I do want to write about the compounding aspect of GLP-1s. When the drug became extremely popular, pharma companies didn’t know what to do. A drug? Extremely popular? In a non-addictive, celebrity-vibes kind of way? I would have loved to hear the conversations happening in the halls of Novo Nordisk.

More importantly, the pharma companies manufacturing GLP-1s, all of which are still on-patent, didn’t have the supply chains necessary for an explosion in popular demand (I write a lot about supply chain fragility, but I wouldn’t call this one of those cases. Brand name drugs usually have fairly robust supply chains; this is a once-in-a-blue-moon scenario in which a brand name drug became popular).

So GLP-1s became difficult to get. At the same time, even those who could access the drug found them expensive, because again, they were still on-patent. And insurance companies (including Medicare), were only covering GLP-1s for specific indications that didn’t include wanting to look skinny on Zoom calls.

But we live in a society that’s great at ingenuity when there’s a profit motive and a bunch of people who want to look good, so compounding pharmacies came to the rescue. Compounding pharmacies are legal entities that have the ability to do some of the last steps of drug manufacturing at a small, individual-level scale, including adding flavors or producing the liquid form of a drug that usually comes as a pill. Compounding pharmacies don’t always have the best reputation, but they’re an important component of the pharmacy system.

Telehealth and skirting the rules

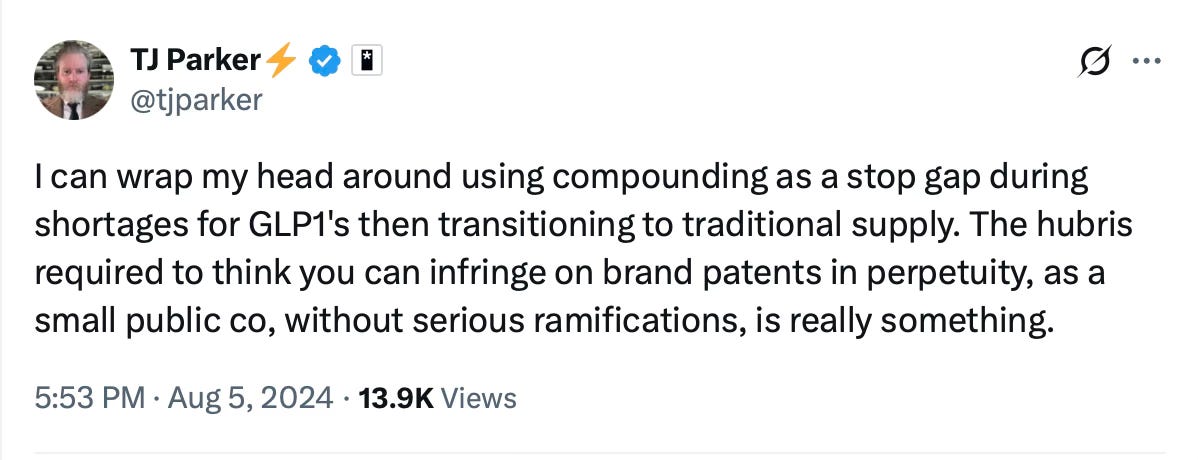

Then in 2024, telehealth companies that were struggling1 saw a path to juice their sales. The FDA had declared GLP-1s to be in shortage in 2022, opening the door to compounded GLP-1s.

Hims & Hers, along with other telehealth companies, announced plans last year to sell compounded GLP-1s for a fraction of the price of the brand name, suddenly directly competing with a brand name pharma company that already had that drug on patent. This was legal because the drug was technically in shortage. But it was no longer in shortage per the FDA as of April 2025, making continued compounding…an extremely bold move.2

Meanwhile, Novo Nordisk, the manufacturer of Wegovy and Ozempic, was building its argument against compounded GLP-1s. I read through the Federal Register comments written by pharma companies for a longer (paid) piece I did on pharma tariffs.3

Many of the companies asked the Trump administration to continue to exclude pharma products from any tariffs. Novo Nordisk specifically requested that the administration address imported generic semaglutide, which is being shipped in very sketchy pallets (bolding mine):

…the Partnership for Safe Medicines found that product codes and paperwork accompanying foreign, non-Novo Nordisk sourced API presented for entry into our country contained numerous “red flags.” For example, shipments listed unlikely manufacturers, such as a major hotel chain, a fitness center, and a public school in Canada.

Novo Nordisk's independent test purchases have revealed that most semaglutide is being imported into the country from Chinese API suppliers and these findings also highlight the unlawful tactics employed by these entities to mislead consumers regarding the nature and origin of their products. Test purchases have identified mislabeled items such as “White Pigment” on packaging or “Adhesive” on import documents. Novo Nordisk has even obtained illegal shipments from China claiming to be “semaglutide” that are deceptively packaged as kitten food and facial masks. These imports into the country continue despite not meeting federal requirements for API shipments.

It’s a testament to how much people want to be skinny that this is what they are injecting themselves with.

Here come the lawyers

Despite Novo Nordisk’s strategy of making clear how fragile generic supply chains are (a goal I share), I was surprised it took the pharma company so long to go after Hims & Hers specifically (maybe the lawyers were too busy saying that no, they meant to let their Canadian patent expire). But on Monday of this week, Novo Nordisk finally announced that they would no longer partner with Hims & Hers — a partnership that lasted about two months — because the telehealth company is continuing to provide compounded GLP-1s, even after the FDA lifted the shortage declaration. Novo Nordisk, meanwhile, is offering a cheaper, cash-pay version of Wegovy, available direct to consumer through its new NovoCare Pharmacy.

Hims & Hers stock dropped sharply as a result.

The company’s CEO, Andrew Dudum, tweeted in response, arguing that Novo Nordisk was trying to force Hims & Hers to only prescribe Novo Nordisk’s GLP-1s, regardless of what was best for the patient. He framed their compounding as a response to Novo Nordisk’s anticompetitive tactics.

I’m all about taking down anticompetitive behavior, but Dudum’s response strikes me as insincere. Is it populist to compound drugs? The cash-pay prices for these medications are undoubtedly expensive, and the patent system certainly preferences big money pharma corporations — but if I’m calling balls and strikes, this one feels like they got caught out.

The battle is ongoing, but my money is on Novo Nordisk (not literally — I don’t have investments in any of these companies).

In 2021, I wrote about telehealth becoming a commodity. I differentiated between telehealth providers and companies that used telehealth to deliver a defined care model. In the four years since that piece, I’d say I was 90% correct — telehealth is indeed a commodity. I was wrong in thinking that many companies would continue to be differentiated; many are themselves commodities now, offering prescriptions as a service. The drugs aren’t addictive (except, ahem, for Done and Ahead, rip), but they’re more or less a prescription mill. There are, of course, exceptions.

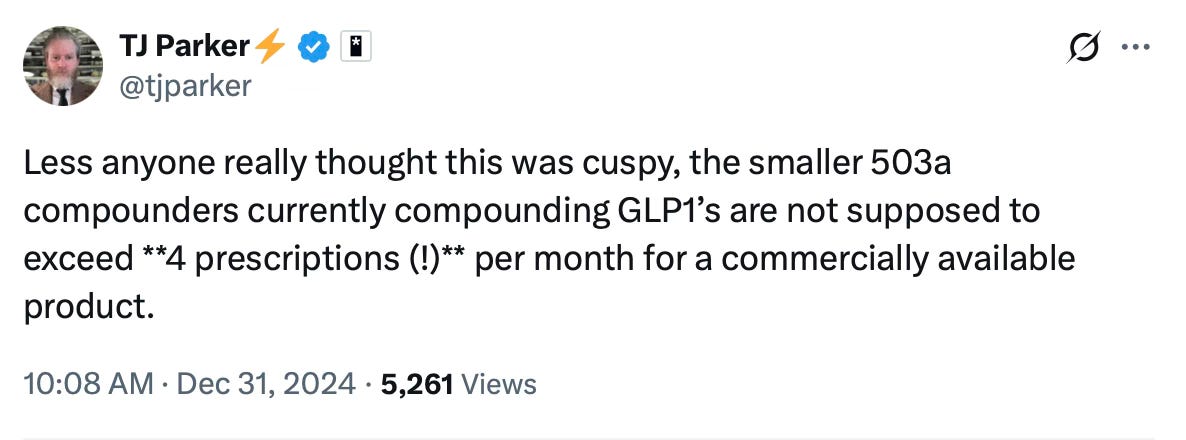

If you’re like me and want to see the FDA’s guidance on GLP-1s for both regular compounding pharmacies (503A pharmacies) and compounding pharmacies that are registered to produce in bulk for medical practices (503B pharmacies), it’s available here.

Please consider subscribing! These posts require a lot of research, and subscriptions help support that work.