PaaS companies and telehealth engagement numbers

It looks like patients might need a front door

Last week, Aetna and Teladoc announced a reformatting of their services into something called Aetna Virtual Primary Care. The new service, targeted at self-funded employers and integrated with CVS Health, will allow members to have a continuous relationship with a primary care doctor, and no-referral-needed relationships with (in-person) specialty docs.

This isn’t very different from Teladoc’s existing urgent care model,1 but that’s not the point. To me, this appears to be an attempt by Aetna and Teladoc to reformat the “front door” to increase patient engagement.

The need for a patient front door

Asking patients to use telehealth goes against the habits they’ve developed over a lifetime of accessing the traditional healthcare system. When a patient feels sick, do they automatically think of Teladoc? Or the in-person urgent care down the street? How do you start to guide patients toward telehealth services? Even before that, how do you let patients know which sets of symptoms are appropriate for a given telehealth platform?

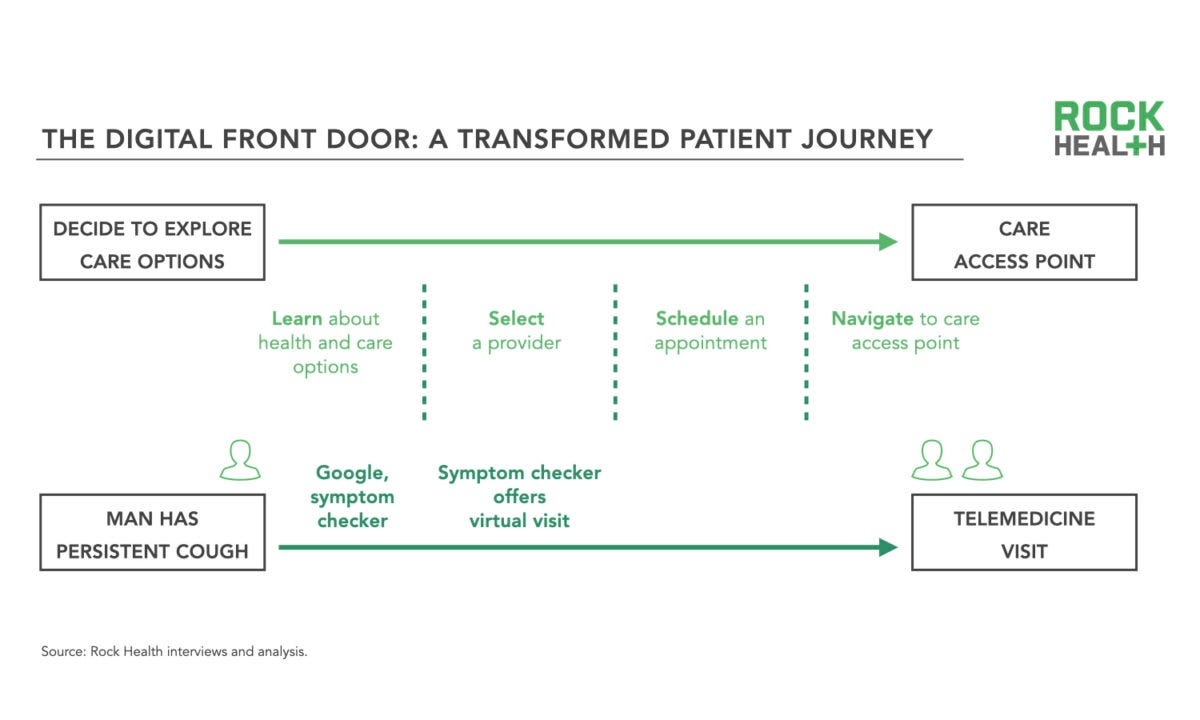

Where and how a patient gets care is guided by the “front door,” a term for the patient journey from deciding to explore care options to actually accessing care. Traditionally, the front door was the patient’s primary care doctor, who guided the patient through care and/or referred them to a specialist. Now that primary care doctors are no longer the gatekeepers they once were, the journey has become much more fragmented.

Digital health companies, however, have the opportunity to remodel the front door.

Rock Health provides this useful map of a patient journey in a traditional healthcare model (top) and a reworked patient journey using a digital solution (bottom).

To date, whether or not a company puts effort into reworking the front door has largely depended on what audience they’re selling to. Companies selling to patients put a lot of work into making sure their service is both marketable and easy to use. Companies selling to insurers and employers have a much different set of incentives.

Now that the telehealth market is starting to mature, though, this divide is becoming more noticeable.

Companies choosing to sell to insurers and employers without thought to the patient front door may face challenges with patient engagement.

PaaS telehealth and patient engagement

Patient engagement is a particular problem for telehealth companies using the PaaS (platform as a service) model.

This is because PaaS telehealth companies—companies that use their platform technology to connect patients with doctors—haven’t historically had to put much thought into care integration. The largest PaaS companies (Teladoc, Amwell, MDLive) were conceived as a platform product to sell to insurers and employers; it didn’t matter if the patient had a longitudinal care journey as long as they got their immediate problem fixed. For that matter, it didn’t really matter how much patients used the service as much as it mattered that they had access to it as one of their benefits.

In other words, telehealth PaaS companies have a lot of market share and a big pool of patients…but they don’t have a front door so much as an open-air marketplace. Patients are left to decide what services they need and what kind of doctor can provide those services, even before they have to schedule the appointment and remember to log into the app.

This kind of telehealth may be more convenient than driving to a doctor’s office, but it requires the same number of steps—and if a patient is used to driving to a doctor’s office anyway, a PaaS telehealth company will struggle to keep that patient engaged.

In other words, without a clear digital front door or integrated patient navigation services, patients confronted with a PaaS-oriented telehealth service are left with too many options and not enough guidance.

Newer integrated care models, many or most of which were conceived to sell to patients first, rather than insurers, have circumvented this problem in a few different ways. One Medical, for example, has a front door that provides a list of common conditions that patients can self-select into. A patient can recognize their condition, realize they’re in the right place, and let One Medical handle the rest.

Other companies build their digital front door around condition-specific marketing and an integrated care model that bundles a large portion of the care for that condition.2 Then, when a patient needs Crohn’s disease care or gender-affirming hormone therapy, they can easily enter the front door of the telehealth company specializing in that condition.3 (Of course, patient-first telehealth companies have their own challenges; namely, selling to insurers and employers.)

Teladoc is building a front door

PaaS services like Teladoc have realized this and are starting to build new, more patient-centric front doors to increase engagement.

As of a July investor call, Teladoc’s annualized utilization rate for members is just above 20%. This rate appears to be stagnating; it increased by about 5% since last year, despite the bump in overall telehealth adoption nationwide caused by COVID-19.

To increase patient engagement, Teladoc executives on the call emphasized new projects they’re developing, including the Aetna Virtual Primary Care service. The overall strategy, according to Healthcare Dive, is to “achiev[e] an evolution from episodic urgent care services to a more comprehensive suite that includes programs for mental health, chronic care, weight management and primary care.” It’s condition-specific and longitudinal, more like an integrated care model and less like a PaaS company.

I’m not the first person to suggest that this is the next step for telehealth companies. In a blog post from February, investor and healthcare writer Chrissy Farr interviewed Micheal Yang of OMERS Ventures, who said [emphasis Farr’s]:

There’s also the opportunity to use navigation to direct people to existing benefits that might otherwise be under-utilized, whether it’s Livongo/ Teladoc or Lyra or Omada Health. This is really critical. Most health benefits solutions garner single percentage point utilization.

The problem: Patients don’t really know when to use telehealth, and they don’t think of telehealth when they start to feel sick. The potential solution: Add a better front door.

Conclusion

The shift by PaaS telehealth providers into offering more of a digital front door may be increasingly important as insurers and employers start to exert downward pressure on PaaS telehealth companies’ pricing models. Quoting Michael Yang from Chrissy Farr’s piece again:

…We’re seeing more of a shift to “per engagement” business models, versus per member per month (PMPM). So the revenue opportunity here could be impacted in the long-run if digital health vendors don’t figure out a way to get more employees engaged.

If this continues to be true, PaaS companies in particular will be looking to add digital front doors to their services. In this, they have a lot to learn from integrated care model companies. And insofar as that requires more attention to what the patient journey actually looks like, I’m all for it.

This information shouldn’t be taken as investment advice (obviously), and the opinions expressed are entirely my own, not representative of my employer or anyone else.

This is beyond the scope of this article, but Teladoc’s approach has me wondering what primary care will look like in 10 years. I don’t have an answer, but I found this related Gist Healthcare podcast episode interesting.

This isn’t a new business model for healthcare. Hospitals have also competed by making their “front doors” more attractive to patients; the most obvious example is a hospital Center of Excellence that promises whole-person, condition-specific care.

I really believe in the condition-specific telehealth model—which is why I work for one of the companies pursuing that model. Although my bias is unavoidable here, I purposely chose example conditions that other companies specialize in. And I’ll reiterate that this is my independent work, not related to my company at all.