Pharmacies are closing and...Dollar General...is stepping in?

Or not.

Before Thanksgiving, CVS announced plans to close 900 stores starting next year. The company will also be converting additional stores into Health Hubs, where consumers can access basic health services. This is part of CVS’s broader strategy to provide healthcare and slowly move away from being a traditional retail pharmacy.

This grabbed my attention for a few reasons. First, because CVS is part of a broader trend: The number of pharmacies in the U.S. has been declining slowly. Second, because the CVS news was taken positively by market analysts looking at it from the perspective of...Dollar General.

Why are pharmacies closing?

Pharmacies are closing because the margins are getting tighter. While the exchange of money in the pharmacy system is complicated, the most aggressive reason behind this margin-shrinking appears to be pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs.

I go into a lot more depth on the role of PBMs and the relationship between PBMs and independent pharmacies in an article I wrote last February. In short, PBMs act as financial middlemen between patients, insurers, and pharmacies by reimbursing pharmacies for fulfilled prescriptions.

There are just a few major PBMs in the U.S., nearly all owned by a major insurer. That scale gives PBMs an extraordinary amount of leverage in negotiating with pharmacies—especially independent pharmacies, but retail pharmacies as well. The result is all sorts of contractual provisions that benefit the PBM at the expense of the pharmacy.

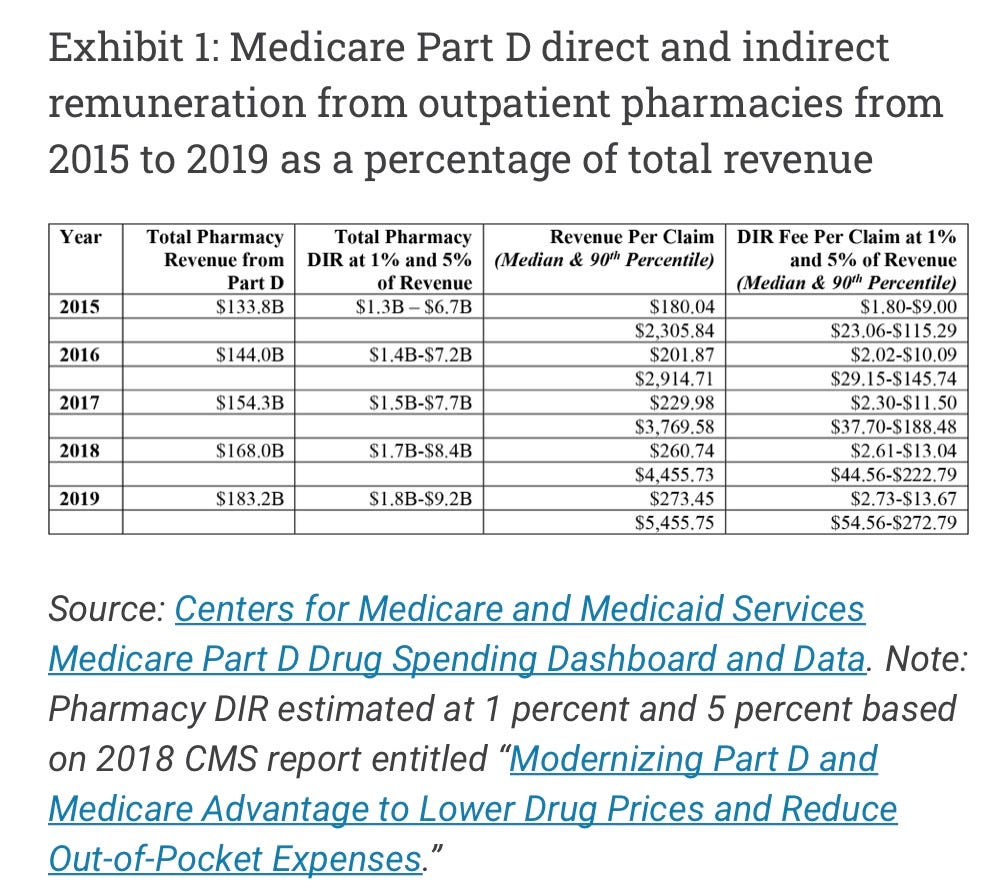

One of the most notorious provisions is Direct and Indirect Remuneration (DIR), also known colloquially as “clawbacks.” These are fees the PBM has already reimbursed to the pharmacy, on behalf of both privately insured and Medicare Part D patients, that the PBM is contractually permitted to take back during the year. These can include adjustments on the final sale cost of the drug, payments for not hitting contractually obligated quality metrics, or a pay-to-play fee to remain in the PBM’s preferred network. Oh, and these fees have increased by 450 times from 2010 to 2017, according to CMS.

The quality metrics situation is particularly frustrating. As a recent article in Health Affairs puts it (emphasis mine),

If pharmacy DIR is collected after the point of sale at the end of the year in an aggregated fashion rather than at the claim level, the pharmacy may have little ability to review and correct its performance in the following year. Additionally, pharmacy performance typically involves a comparison to peer pharmacies’ performances, but pharmacies do not know the comparison group they are measured against. Information on pharmacy performance on these metrics are not publicly available, and PBMs do not disclose such information to pharmacies in their networks. Therefore, pharmacies do not know how they are ranked among their peers or how much DIR they should budget for at the end of the year.

These fees mostly affect pharmacies, but they can also directly affect the prices patients pay. A 2018 Kaiser Health News article describes it like this:

After taking your insurance card, your pharmacist says you owe a $10 copay, which you pay, assuming that the drug costs more than $10 and your insurance is covering the rest. But unbeknownst to you, the drug actually cost only $7, and the PBM claws back the extra $3. Had you paid out-of-pocket, you would have gotten a better deal.

Multiply that rate by each prescription, and pharmacies can end up owing thousands in DIR fees every month. This keeps the margins that pharmacies can make on each drug low. How low? In 2020, a Western PA pharmacy closed because it was losing money with 80% of the prescriptions it filled.

Health Affairs also published this handy chart estimating the amount of DIR fees based on CMS data.

So why is this good for Dollar General?

CVS’s announcement prompted Chuck Grom, a retail analyst with Gordon Haskett Research Advisors, to note that the announcement “has the potential to accelerate [Dollar General’s] opportunity.”

Unfortunately I could only find this sentence in CNN’s coverage of the CVS announcement, and not the actual note Grom sent to investors. So all I can do is guess what inputs Grom is using to make his analysis.

Interestingly, as CVS is pulling back from its retail strategy, Dollar General is leaning deeper into its own. Dollar General’s initial forays into healthcare have been entirely retail-oriented. Even its first “healthcare product” offerings are little more than retail products that have something to do with the human body:

Among other things, this will include an increased assortment of cough and cold, dental, nutritional, medical, health aids and feminine hygiene products across many of its Dollar General stores. | Dollar General press release

Dollar General has also floated the idea of doing pharmaceutical delivery, eye care, or telemedicine, and the company has hired a CMO to lead the charge. At the same time, they’ve said they won’t open a pharmacy.

Which leads to a few questions: Does this mean they’ll partner with an existing pharmacy? Will they bring on doctors? Will they take the Walmart strategy of referring out to entities with whom they have favorable contracts?

The question that looms biggest in my mind, though, is why are all the business publications so excited about Dollar General's involvement? Before I started doing research for this article, I assumed I’d uncover some major exciting idea I hadn’t thought of. Instead, I keep coming across headlines like “It Doesn't Pay to Bet Against Dollar General” with no real explanation for why.

The biggest feature that commentators seem to point to is that Dollar General has a big rural presence. But Walmart also has a big rural presence and that hasn’t changed the company’s ability to make headway in healthcare—they’re still trying to figure out the cash-pay system.

I guess Dollar General could start partnering with other companies, and sure, why not? But what makes that special?

The big problem with rural care over the last few decades is that there just isn’t that much money to be made from treating many rural populations, unless you’re going to do value-based care. (And if Dollar General figures out value-based care before anyone else, someone let me know; I’ll have some very serious soul-searching to do.)

Then again, if you’re going to do value-based care, maybe it shouldn’t be part of a store that only recently started dabbling in selling food that isn’t prepackaged and heavily processed.

Finally, I just don’t understand how CVS closing stores paves the way for Dollar General. Not only has Dollar General explicitly said that they’re not opening a pharmacy (which would be the most straightforward way Dollar General could take CVS’s place), but CVS is opening more Health Hubs, which potentially encroaches on the more interesting part of Dollar General's health strategy, which is to offer basic healthcare. (I’m not interested in the idea of Dollar General selling feminine products unless they figure out how to sell a box of brand-name tampons for $1. Those things already have too high a markup.)

Conclusion

Call me when Dollar General starts a food pharmacy.