What a time to be an oncologist

The rush to capture oncologists' attention

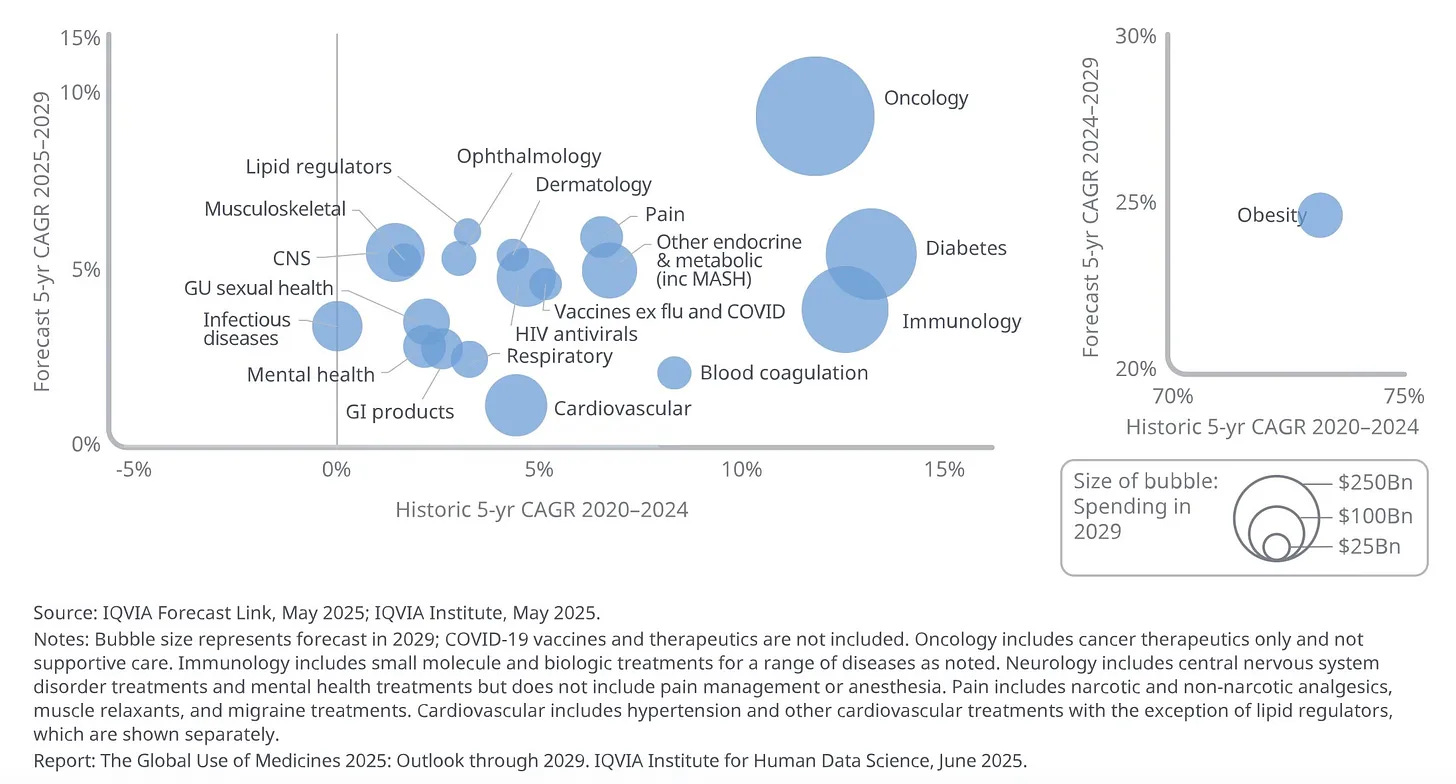

High-value, novel drugs seem to be taking up a lot of the air in the conversation about the future of healthcare. People haven’t given up on value-based care explicitly, but there’s a lot more skepticism and willingness to admit that it hasn’t worked the way it was supposed to.

So value-based care is complicated (something I have been trying to write about, stay tuned). Administering and paying for high-cost drugs might be less so, and there’s probably more money to be made. Which brings us to oncologists, the topic of today’s newsletter. These are specialty physicians who prescribe a lot of drugs. This makes oncologists a very attractive target for pharmaceutical advertising.

Reaching oncologists

To reach oncologists (and other physicians), pharmaceutical companies are spending more and more on digital advertising, a move away from traditional TV ads. Industry data shared with Fierce Pharma suggests that healthcare and pharma companies spent nearly $25 million on digital advertising in 2025, a number that is expected to grow. These more targeted ads are, in part, being served to doctors on platforms like Doximity, a popular social network for doctors, and OpenEvidence, an AI-powered medical search tool that’s rapidly growing in popularity.

Related articles

Of course, it’s not quite as simple as: advertise to oncologists, reap the rewards. Payors, health systems, and PBMs often have clinical practice guidelines and formularies that purport to be the most cost effective and evidence-based set of therapies for a specific indication.

These guidelines can be fraught. Not only does each player developing a formulary have its own agenda and incentive structure, but the physicians who are hired to help develop these lists are, on average, more likely to have conflicts of interest with the pharmaceutical industry. And these lists can determine what a payor is willing to cover and what a health system is willing to stock.

It’s also important to note that the financial health of an oncology clinic is more heavily linked to pharmaceuticals than in other specialties. Oncology clinics that provide infusion services encounter all of the complicated dynamics of reimbursement for highly expensive drugs. Many reimbursement models have the clinic purchasing the drugs in advance and taking the revenue risk until the payor reimburses for a specific treatment (I wrote about the dynamics of infusion services here and here. The TL;DR, it’s very complicated). This can make oncology clinic cash flow difficult to manage, and it’s driving the decrease of independent oncologists as they are acquired by health systems and other players.

Why not just acquire them?

Wholesalers — the middlemen between pharma manufacturers (making the drugs) and pharmacists/health systems (buying the drugs) — are increasingly acquiring huge percentages of the oncologists in America. In 2010, McKesson acquired US Oncologists, then worth more than $2 billion and serving nearly 3,000 oncologists. In 2024, Cencora and Cardinal Health took similar steps, acquiring national groups of oncologists.

That seems like kind of a weird play, wholesalers aren’t traditionally in the business of serving patients at all. But with a limited number of oncologists in the U.S., wholesalers have discovered that it’s easier to acquire these physician groups and have oversight over prescription decisions rather than having to advertise and deal with all of the complicated dynamics of how oncologists choose which drugs to distribute.

What’s next?

For those who can’t afford to buy oncologists and make them use their drugs, some startups are experimenting with new advertising channels. The most-discussed player in this space right now is OpenEvidence.

Kevin O’Leary of Health Tech Nerds had a great write-up of the search tool last week. While its advertising model right now is successful and fueling rapid growth, its valuation almost demands that it move beyond advertising. As he wrote:

It’s worth noting that OpenEvidence’s biggest competitor, Doximity, is currently generating ~$620 million in annual revenue and has a market cap of around $7.5 billion. The entire healthcare digital advertising market in the US is estimated at $26 billion in spending. Point being, in order for new investors to see returns here, it seems OpenEvidence will need to redefine the market entirely.

But what I thought was really interesting was Kevin’s interpretation of OpenEvidence’s next stage of the business model. He noted that OpenEvidence founder Daniel Nadler implied that OpenEvidence’s next iteration may be medical superintelligence, or a specialty-specific expert. But the advertising model presents some serious problems. As Kevin puts it:

If you’re a cancer doctor in rural Georgia, and you know this platform is serving you up ads from oncology manufacturers, are you really going to trust it as your “default operating system of medical knowledge” when trying to answer challenging medical questions about your patients?

This next comment might seem like a non sequitur to end the newsletter, but bear with me. I was talking to someone recently who noted that shareholder-only business models often inflict a grave moral injury on their employees. Employees have to follow directives that might not make sense, and they’re forced to interface with bewildered and angry customers.

To me, it seems like this is increasingly happening in medicine. OpenEvidence currently gives doctors a high-quality search experience in return for their advertising attention. But the advertising sales page emphasizes that physicians are often using the search engine during “high stakes treatment decisions” and that 75% of its usage is during office hours — which implies, to me at least, that part of what they’re selling is physicians’ busy-ness and their need to make quick decisions without thinking too much about the incentive structure behind what they’re seeing.

Over time, and paired with the loss of independence that oncologists are experiencing as they’re told which drugs to use from everyone from wholesaler-acquirers to the very search engine they rely on, the profession may begin to erode the way it has for many other specialties.

is there a cure for zionist cancer yet.